Uwanosora is a great, new Japanese band who released their self-titled debut album last year. The following is to my knowledge the only published interview they’ve done so far and it’s an interesting, very in-depth read. Two members of Uwanosora are releasing a new album next month under the name of Uwanosora ’67 which you would also do well to check out.

I definitely recommend giving a listen to this band especially if you’re a fan of, say, Lamp.

Original interview, text: FUKUROKO-JI (parts one, two, three & four)

English translation: Henkka

Uwanosora on the web: website, iTunes, Twitter: Kadoya, Oketa & Iemoto

Note: You can buy Uwanosora from iTunes or CDJapan (physical CD, PayPal accepted).

(L-to-R) Hirohide Kadoya (guitar, songwriting), Megumi Iemoto (vocals) & Tomomichi Oketa (guitar, songwriting)

As a resident of Kansai, the first time I heard the term “city pop” was around the time I moved from my hometown of Nara to start university in Osaka. I think the reason I didn’t really get what the term meant was because, for me, “city” had always meant “Tokyo.” Sure, I’d always lived right next to Osaka, but to me Osaka was a place that never had the image of an urban, polished city — I’d always just thought of it as this area that had been forcibly made to flourish. But these feelings of mine towards Osaka were also what made me so interested in the “city,” and once I’d gotten to know the streets of Osaka a little bit, I started imagining just what Tokyo must be like in comparison. This was also when I first became interested in the musical genre of city pop, but deep down inside, I was cynically thinking to myself how “this city pop stuff is surely something only people living in the suburbs of Tokyo are able to truly understand.“

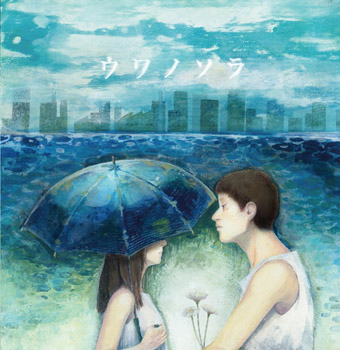

This blog, FUKUROKO-JI, is a place where I’ll be interviewing people I’m personally interested in. My honorable first guests and fellow Kansaians, Uwanosora, are a three-piece band consisting of Hirohide Kadoya (guitar, songwriting), Megumi Iemoto (vocals) and Tomomichi Oketa (guitar, songwriting). Formed in November of 2012, they produced an eight-song demo tape (unreleased) after just two months of being a band, and this July they released their first full-length album, Uwanosora, through Happiness Records.

I first heard of this band through the Nara record store Django, whose owner, Mr. Matsuta, I spotted praising Uwanosora on Twitter. I immediately bought it, and upon listening to it I was overwhelmed by the level of songwriting and arrangements that were way beyond the level of your average debut indie album. I desperately wanted to ask them about their approaches to songwriting and about the songs included on the album, and so with nothing to lose, I approached them about doing an interview. And, admittedly, at the back of my mind I did have an ulterior motive of wanting to know more about these people who — despite not living in Tokyo — had managed to release an album full of city pop.

Interview & text: FUKUROKO-JI

— First off, could you tell us about how the band first came to be?

Hirohide Kadoya: Me and Oketa were good friends in university — we first met at a teaching methodology class. (laughs) One day I came to school wearing a Tatsuro Yamashita concert hoodie (the “PERFORMANCE 2002 RCA/AIR YEARS SPECIAL” one) and Oketa asked me if I liked the man. The more we talked, the more we noticed how similar our tastes in music were.

Tomomichi Oketa: (laughs)

Megumi Iemoto: I wasn’t previously acquainted with these two. I made this demo tape with a cover of EPO’s “Kimi to Boku” to audition for a performance at the university’s open campus stage. The two heard my demo and invited me to join the band.

Kadoya: We did consider a few other singers as well, but it was all people who sang in this deep R&B, black music style. Iemoto was the most casual, pure singer of the candidates, and she had the kind of soprano voice we thought would make for the best fit for the kind of music we wanted to do.

— Were there always just the three members since the beginning?

Iemoto: No, initially we did have more people.

Kadoya: We originally got together with friends from the university to make something together to commemorate our graduation. It was supposed to be a collection of songs with another girl doing the singing. Oh, and Oketa had decided that he was going to be the arranger…

Oketa: Yeah, that didn’t exactly work out as planned… (strained laugh)

Kadoya: I felt bad because even though we’d asked Iemoto to help us, the project just wasn’t moving forward at all. So in November 2012, I said “alright, I’m going to be the arranger, got it?” and I got everyone’s songs in order. If there were songs I didn’t particularly like or whatever, I’d tell whoever wrote it that I wouldn’t be able to work with that piece. And before we knew it, it was just us three left.

— Your initial intention was to just make this relaxed commemorative thing together, but then you got strict and nit-picky when it was time to choose the songs?

Kadoya: I am nit-picky, yeah. Even though that first demo tape was going to be our first and only work, I just wasn’t entirely happy with it, and that’s why we later went about making Uwanosora.

Oketa: Once we’d settled on these three members, I went over to Kadoya’s house for about two weeks that we just spent making demos together.

— And one of those demo songs was “Umbrella Walking“, right? You ended up deciding against releasing those demos…

Kadoya: The songs were all over the place. There were country songs, jazzy songs… it was too varied to make for an enjoyable listen as a full album.

Oketa: We were never even thinking about actually releasing it. We just wanted to finish it and be done with it.

Kadoya: Once we’d finished recording the demo, we were talking about how it’d be nice to get a proper mix and master for it done by someone in Tokyo. So we called this phone number we found on the back of a RYUSENKEI CD, and that phone number belonged to Happiness Records who would later go on to release our debut album. They told us they would love to release something by us once we figured out which direction we wanted to take our music, and that’s how we got started writing the songs on Uwanosora. The recordings ended up taking longer than expected and that’s why we only finally managed to release the album now.

— How long did it take you to write the songs on it?

Kadoya: We were done writing everything after two months. That was in February 2013 or so.

— So you started making the first demo tape in November 2012, and three months later you’d already finished all the songs on the demo and on your debut album… that’s amazingly fast. But then the recording of the album took you a year and a half, and you finally released it in July.

Kadoya: The album had a lot of supporting musicians, so there were many scheduling issues.

Iemoto: But as for the vocals, we’d already finished everything by the end of January.

Kadoya: Right. The time between then until the release felt really, really long… Anyway, all the songs we’ve released up until now were all written during the first six months of the band’s existence.

— How did you come up with the band name, by the way?

Kadoya: That’s a long story… We were set to play with rourourourous last year and we just needed to have a name before then.

— You didn’t have a name until that?

Kadoya: No. We were writing down all kinds of ideas, and when I asked Cunimondo (Takiguchi) of RYUSENKEI, he told me we should name the band “Hiyashichuuka Hajimemashita.” I was like “hey, I like that!” but when I proposed it to the label, they got angry and asked what the hell I was thinking. (laughs) Finally, we ended up going with the word “Uwanosora” we found on a Takahashi Matsumoto novel called Kaze no Quartet. It was Iemoto who suggested we should write the name all in katakana because that way it looks like it’s just a bunch of the character “ノ” in a row (ウワノソラ Uwanosora), which I thought was a fun idea.

— Wow, you’re right, it does look that way! That’s funny. I suppose your music could be classified as city pop, but I’d argue your kind of sound is really rare in the Kansai area, especially considering how young you all are. Before meeting you I really couldn’t picture the kind of people you were at all.

Oketa: I think it’s only really in the live music scene where the “local flavor” of bands comes into play. Every city has its own live scene, but we’re a group that doesn’t go out to play live all that much, so we aren’t really all that influenced by what’s happening around us. All three of us like the same kind of stuff. I think we would’ve ended up doing the same kind of music regardless of our city of origin.

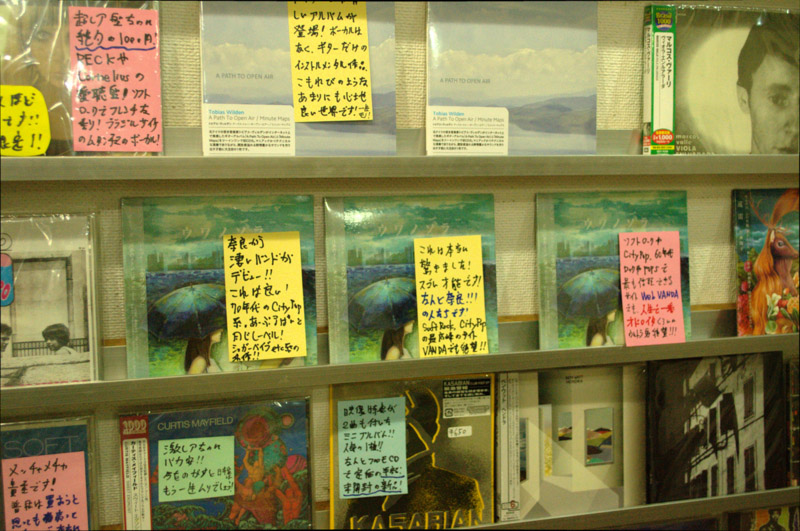

During the interview we visited the Django record store in Nara.

— You were all studying music as your major in university. This is something that surely you knew would influence your future paths in life, right? When did you first think you might want to seriously pursue music as a career path?

Iemoto (is pointed to at by Kadoya): Huh? Me first?!

Kadoya: I just realized it’s something I’ve never asked you before.

Iemoto: …I wonder? Going from junior high to high school, I just remember thinking how I didn’t want to study anymore. We had several courses available at my high school, and a music course was one of them. The only real previous experience I’d had with music was playing the piano from elementary school up to the start of junior high school, but I was like “well, I do like singing, I guess,” so I ended up choosing the music course anyhow. When it was time to think about universities, I thought I’d just stick with singing and I applied to a music school.

Kadoya: I never knew if I wanted to become a musician. I still don’t, to be honest. Originally I was just going to apply to a normal university and study like everyone else, but I actually ended up doing nothing at all for two years following high school. I just couldn’t get motivated to do anything. I lived in Kanagawa back then, but I’d always yearned to be closer to Shikoku and to the south. And so eventually I found my university and got in, but back then I was still thinking I was going to go back to Kanagawa after two years or so and start all over again. But for some reason it looks like I’ve stayed here. (laughs) Anyway, for me, I wasn’t seriously thinking about wanting to work in music in the future or anything.

— How about you, Oketa?

Oketa: It was around my second year of junior high school. Since I was very little I’d always liked early Kansai folk, artists like Saito Nakagawa and Kyouzou Nishioka. I remember my dad always playing that kind of music in the house. My dad was also a guitar player, and even if it wasn’t the biggest influence to me becoming a musician, there was always a guitar available to me. I also bought my own electric guitar in around the second year of junior high school. Then near the end of my first year in high school I happened to hear the ending theme to Hideo Okuda’s film In the Pool, which was a song by SUGAR BABE. That’s when I finally had my “aha” moment.

Kadoya: “DOWN TOWN,” right?

Oketa: Right, the song’s called “DOWN TOWN.” It’s preceded by Eiichi Otaki‘s “Niagara Moon ga Mata Kagayakeba” playing in the background in the last scene, and I really loved the way those two songs led into each other. I think it’s thanks to me seeing that scene that made me who I am today.

— In my case, Music Station and all those other TV music programs were in their golden years back when I was going through puberty, and so you’d have to watch them every week if you wanted to know what everyone was talking about at school. So in a way it feels like I was forced to like all kinds of songs back then. But in Oketa’s case, you always had your dad’s influence and, with that, a strong foundation for music. You weren’t forced into it so to say.

Oketa: Yeah. The initial reason I started a band was thanks to being influenced by BUMP OF CHICKEN. I’m pretty sure theirs was the first CD I bought, too. After them, I’d just listen to everything I could get my hands on. I’d set a criteria, like the band had to have four members or whatever, and then I’d go on to discover bands like Quruli, who would then lead me to learn about Haruomi Hosono… and gradually I’d broaden my horizons. Thinking back, I was drawn especially to anyone related to the Tin Pan Family. Every one of those guys had amazing roots: SUGAR BABE, for example, used to sing backing vocals on Yuumin’s early albums. I heard Kyouzou Nishioka’s “Rock-a-Bye My Baby” through his connection to Haruomi Hosono, and then I went home and discovered we had his records laying around which I’d then listen to. So yeah, I never had to force myself to listen to anything.

— It sounds like two of you (Oketa, Iemoto) were inclined towards music from very early on, whereas Kadoya just sort of stumbled upon it.

Kadoya: I did always love music though. I’d buy all these music magazines every week, and I’d skip school just so I could listen to the radio.

— What kind of music did you enjoy hearing on the radio?

Kadoya: I thought songs like Stevie Wonder’s “Overjoyed” and Joe Cocker & Jennifer Warnes’ “Up Where We Belong” were cool. I was drawn to how grown-up they sounded.

— Oketa and Iemoto were mainly listening to Japanese music whereas you seem like you were more of a Western music fan.

Kadoya: Back in elementary school I used to listen to stuff like the artists produced by Komuro, Mr. Children, and Spitz, but apart from those I also listened to lots of oldies. When you listen to some of those compilations, you find so many good melodies, right? Like, I could listen to Mamas and the Papas’ “California Dreamin’” for ages. Also, Led Zeppelin and David Sanborn… I’m not sure if I even had a clear favorite, I just listened to everything all at once in elementary school. It was only in junior high when I finally started to grasp my own preferences. “It seems I quite like this genre they call AOR.” (laughs) So I headed over to Tower Records and bought albums like Finis Henderson’s Finis and Jimmy Messina’s Oasis. I liked that grown-up, “seashore” kind of feel. Although nowadays it feels like it’s died down, back when I was a kid, the weekly Roadshow movie broadcast slot on TV felt like it was in its prime. So I’d be watching when they broadcast something like Terminator, and I’d just love the music in the scenes where Schwarzenegger goes to the bar or where he’s driving a car and stuff. That whole 80s world seemed so cool to me. I was always drawn to it.

— Iemoto, was there any artist or band in particular you remember being inspired by?

Iemoto: No, not really… Up until junior high school I was doing classical ballet because I wanted to become a ballerina, so ballet music is basically all I listened to.

— To think that you came from such a background…! But you nevertheless immediately went for music when it was time to choose your high school course?

Iemoto: Yeah. Still, there was no one I particularly admired. The first time I sang in front of people was at my high school entrance exam and I do remember that the song I chose for that was Rimi Natsukawa’s “Nada Sousou.” My dad liked Yuumin and I do remember listening to her a lot together, but still, it’s not like Yuumin was all I listened to either…

Kadoya: What about Yuko Ando?

Iemoto: But I only came to like Yuko Ando after I got into university. And rather than female voices, I always thought male voices were more interesting. If you asked me to name some names… I really couldn’t think of anyone in particular.

— Still, with Yuumin being mentioned I feel like there was at least something you three had in common between you before you met.

A customer randomly walked in and the members of Uwanosora all wrote their autographs for a fan of theirs for the first time.

Standing in the back is Django owner, Matsuta.

Kadoya: Me and Oketa would make home recordings of our songs, and when you’re recording everything by yourself at home, you can make everything sound just like you want it, right? So when it was time to form a band and get other musicians involved, I was afraid that my songs would no longer sound the way I wanted them to.

— While some people might feel that bringing in new musicians to play their songs is something exciting, for you it was more of a scary thing?

Kadoya: Well, I mean, even if the song ended up being no good… if it was me playing everything on it, at least it would still be a bad song on my terms, you know? I felt that once we got other musicians involved, if they didn’t feel exactly the same way about the song as I did, that song would be ruined. But actually having those musicians in the studio to bounce ideas off of… those people would all have their histories with their respective instruments and so they would come up with all kinds of interesting ideas. I came to learn that it can be very rewarding when you work with people and hear their ideas that can make your song go in whole new directions; directions you could’ve never thought of by yourself. Plus, it’s so fun when you get into a groove together. But whereas Oketa brought in these really high-quality, near-finished demos of his songs, mine were all just of me accompanying myself with only the basic chords and guide vocals.

Oketa: I’m no good at what I do and I have so much trouble getting close to what it is I want to create, so that’s why when we go in to the studio, I want to come prepared with a demo that’s as close to the finished product as possible. The more instruments I already have ready is going to make it that much easier when it’s time to arrange the song, and when we’re working with a large number of musicians, it’s also easier to capture the mood I want the song to have. However, I couldn’t make a demo of me singing my own songs even if I wanted to. That’s why I just make sure to get the instrumentation down and make everything as clearly audible as possible before handing it off. Even so, the finished product will still be a little bit different from my demo, but that’s something I always look forward to hearing.

Kadoya: I’ll sometimes go ahead and change your songs.

Oketa: Yeah, that was pretty amazing to see… (strained laugh)

Kadoya: “Matenrou” has an interlude with an organ part that sounds like Al Kooper’s “Jolie,” which is completely different from Oketa’s original demo he brought in.

Oketa: Only the first measure of it is the same.

Kadoya: He was like “I’m away from the studio for a tiny bit and you go and change my song into “Jolie!”” (laughs)

— Was it during the early jam sessions and pre-production that you started giving instructions to the supporting members?

Kadoya: We’d explain to them our basic ideas behind the songs and show them the parts we were unsure about, and then we’d implement the ideas they had. The fact that we were all music students and that most of them were our friends meant we were in good company and they all had some advice to give. We wanted to make the best of being able to work in an environment like that.

— The diversity in the playing on the album is also apparent when you look at how many supporting members it has playing on it.

Kadoya: Not all of them came from the same musical background as us either, so we’d have to look for something we had in common. With the drummer, for example, he told us he likes Steve Gadd and Jeff Porcaro, so we’d tell him “alright, well in that case, play it like this!” But with the members we didn’t have any music in common with, we would just have to leave it up to their best judgement which would lead to some pretty interesting nuances in the music. Most of the supporting members actually listen to music that’s pretty recent.

— Speaking as Kirinji fan, I was surprised to hear about their bassist, Manabu Chigasaki, also being featured on the album. How did you end up getting him involved with this release?

Kadoya: We recorded everything we could by ourselves, all the way down to setting up the mics and stuff, but we felt worried about recording the drums all by ourselves so we thought we’d go to a proper recording studio in Tokyo to do so. The only problem was, we didn’t have enough money to send our supporting member in Osaka over to Tokyo. So we asked around if anyone knew any musicians in Tokyo who seemed like they might get what we were trying to do with our music, and that’s when Chigasaki’s name popped up. We were like “are you for real!?” (strained laugh) When we met him, I didn’t have to say anything before he was like “ah, yeah, so something like this?” and he played everything perfectly. At the end he said “please keep making music forever” before making a grand exit. (laughs) We’re just some tiny indie band who no one has ever heard of, but he nevertheless did his job without the smallest complaint or hint of any elitism or anything of that sort. You could tell he’s a true professional.

— Did you go watch over those recordings in Tokyo just by yourself?

Kadoya: It was me and Oketa. Other people featuring on the album include Akiko Shiina (Rhodes), Hitomi Yamakami (sax) and Yusuke Ochi (drums), among others. Everyone was over 10 years older than us and they were all such nice people. Each one of them understood perfectly the sound we were going for. When it’s just us working together it can take a really long time to get from our image of a song and actually realize that idea, but they could instantly perform everything perfectly without us saying a word. When we got back to Osaka and told our supporting members there how the Tokyo folks had been, they couldn’t believe it and they were going all “we need to step up our game…”

— And then you did some back-and-forth with the recordings you’d done in Tokyo and the earlier Osaka recordings.

Kadoya: Right. We didn’t have any confidence in the recordings we’d done in Osaka, but surprisingly people were telling us they sounded really good. The drums on “Kazeiro Metro ni Notte” and “Picnic wa Arashi no Naka de” were recorded in Osaka so they sound a bit different; a bit “muddier.” Both drum parts were recorded in the rehearsal studio of our university, so some of that atmosphere is definitely captured on there, too.

— That’s a nice bit of trivia to know. By the way, the lyrics to all songs on the album were written by the guys, right? Iemoto, as the vocalist, did you not ever feel like asking them to let you write some lyrics as well?

Kadoya: It’s not like we didn’t ask, though!

Iemoto: Well, it’s not that I didn’t want to — I’m just not very good at writing them…

— So you’ve never written lyrics before?

Iemoto: Not until completion, no.

— The lyrics on the album are all about “you and me,” from the viewpoints of both a man and a woman. Did you try to be aware of anything in particular especially when singing the lyrics from a male viewpoint?

Iemoto: Hmm…

Kadoya: She’d often ask us about the characters appearing in the lyrics. I think she wanted to sing the songs while feeling what the characters did. If you listen closely, you should be able to hear her sounding slightly different in each song.

Iemoto: (laughs)

— Listening to the album, I was just surprised by all the string arrangements and wind instruments in there, even though it isn’t a major label album. What were you hoping to accomplish when making this album?

Kadoya: It’s a bit of a vague objective, but we just aimed to make music that could continue to be loved for years and years to come. We talked about how we wanted to create something that would be remembered; something that wouldn’t grow stale with the passing of time. Also, we like the sound of instruments from the 70s and early 80s, so we wanted the album to sound similar to that era. In the end, it felt more like something we’d done solely for our own enjoyment. (strained laugh) I still can’t believe we’ve had so many people actually listen to this album.

Oketa: (laughs)

Kadoya: (Takahide) Uchi from WebVANDA wrote a review of our album, and in it he talks about how some songs reminded him of other artists — like that organ part inspired by Al Kooper’s “Jolie.” We intentionally wanted to make it an album where listeners would be able to pick out some of those inspirations. The composition process was also an experiment in trying to follow the musical teachings of Eiichi Otaki and seeing what sort of sound that would lead to when achieved through the use of modern recording techniques and environments.

At Django. On the left are owner Matsuta and a regular customer of the store.

— The album opens with the uptempo “Kazeiro Metro ni Notte.”

Kadoya: The chorus, while being quite uptempo, also has the “earthy” sound of SUGAR BABE, The Isley Brothers or black contemporary music, that whole 70s soul feel. I wrote the interlude to this song at a time when I was listening to lots of Fitness Forever, and I arranged that part with them in mind. I just wanted it to sound gorgeous with lots of brass and strings.

— “Matenrou” was both written and composed by Oketa, right?

Oketa: Right, although like we talked about earlier, it did change a bit with Kadoya’s arrangement…

Kadoya: You first wrote this song back in high school, right?

Oketa: Yeah. My second year of high school.

— I was a little surprised by the lyrics featuring several mentions of skyscrapers, cities, buildings, etc — everything associated with “city pop.” I’m guessing that in reality you didn’t get to see a lot of that growing up in your hometown (of rural Nara), did you?

Oketa: I go to places like Ishikiri (Osaka) and Ikoma (Nara) a lot, and I think seeing all those Osaka-style highrise buildings especially around Ishikiri left an impression on me. I’ve never been good at writing lyrics based on my own experiences; I prefer to start from complete zero instead. That’s why it was actually kind of because I live in the countryside that I was able to write those lyrics.

— So it was seeing those landscapes that inspired you to write the song. Next up is “Sayonara Mugiwaraboushi.”

Kadoya: This was another song whose original demo Oketa brought to us.

Oketa: …Back when it was still this overly serious ballad song. (strained laugh)

Kadoya: The way there are repeating sounds on the first and third beats makes it sound quite folky and kayou kyoku-ish. I wanted to try polishing it just a bit more so I upped the BPM, and because those repeating notes also made it sound a bit like a marching song, I sort of pushed them to the background and added in a lot more notes. The chorus basically sounds like Tatsuro Yamashita covering Bread & Butter’s “Pink Shadow.” The chord progression is very much inspired by Jason Mraz who we were listening to a lot after graduating from high school. We wanted it to have that California/West Coast feel. As for the lyrics, we wanted them to have the escapism and sentimentality of Phoenix’ “If I Ever Feel Better” — even if there is a bit of venom at the end.

— “Margaret” is the only song on which Oketa plays a guitar solo. Compared to Kadoya’s very “solo-like” guitar solos — if that makes sense — Oketa’s solo struck me more as something that just sticks close to the melody of the song and doesn’t try to stand out as much.

Oketa: You know, for me, I never found it all that cool in music when it’s the guitar at the very front riffing and soloing and stuff. That’s why I just tried my best to play it in a way that compliments the song.

— I actually thought it sounded very Takaki Horigome (Kirinji).

Oketa: Ah, yeah. I do prefer Takaki when it comes to Kirinji. But at the time of recording it I wasn’t actively conscious of his playing style — I just wanted to get it over with as soon as possible. It didn’t take more than an hour or two to record it.

Kadoya: It’s a really tasteful solo. I like it.

— During “Picnic wa Arashi no Naka de,” there’s an audio clip of a reporter doing a weather report in the middle of a typhoon. When I first heard the song, I thought this man getting drenched in the pouring rain was like a metaphor for his girlfriend being super angry at him.

(everyone laughs)

— Like, “how many times do I have to tell you to not put lettuce in my sandwich!“

Kadoya: Yeah, we did hear many similar impressions from people. (laughs) Everyone has their own interpretation of the lyrics so I don’t want to say too much, but when making this album, I really liked writing about the varying degrees of commitment between a man and a woman in a relationship — yeah, they like each other, but they’re just different enough to also make things a bit awkward and difficult between them.

— And I think that sentiment behind the lyrics is very “Uwanosora.” Which, incidentally, is also the title of the album.

Kadoya: I wanted this song to sound like something from a different area of music entirely, something like Todd Rundgren, The Beach Boys or Benny Sings, and I wanted the guitar parts to sound a bit like Tin Pan Alley.

— Let’s move on to the second half of the album. For me, I actually felt like “Genkin ni Karada wo Hare” was the one song on the album that sounded quite different from the rest.

Kadoya: The inspiration for this song was Stanley Kubrick’s film, The Killing, whereas influences for its rhythm were songs like SUGAR BABE’s “SUGAR,” Kirinji’s “Asejimiru wa Awai Blues,” and artists like Steely Dan and Marcos Valle. I like songs that are carried by syncopated rhythms.

— So the song was born thanks to you being hooked on that rhythm?

Kadoya: Right. There’s some wordplay in there as well. The lyrics are a bit narrow-minded, but those are just the thought processes of the characters in the song, not ours… Why am I getting so defensive over this? (laughs)

— Does the songwriting process for you two usually begin with a rhythm?

Kadoya: For me, yes. I don’t want our albums to be too uptempo — it’s better to have variety. So I think about the types of songs we need to have based on that. Oketa shows me what he’s been working on and that can then inspire me to think about the kind of song I want to write next.

Oketa: Not necessarily so for me. With my songs the rhythm and BPM will often change based on sudden whims. (laughs)

— Do you come up with the lyrics or the music first?

Kadoya: On this album, I came up with the lyrics first.

Oketa: I can only speak for “Matenrou,” but I seem to remember writing the music and the lyrics at the same time.

— As for the 7th track, “Uwanosora,” did you at any point consider having this song be the opening track of the album instead? The reason I’m asking is because of the chorus ensemble and how on my first listen it reminded me of “Our Prayer,” the opening track off Brian Wilson’s Smile. So you would’ve not only been inspired by the song but also by the song order of the album… Am I overthinking this?

Kadoya: No, I was actually listening to that album when writing this song and we did consider having it as the opening track. But when we put the songs side-by-side and looked at how they all fit with each other, we thought it might be better to have it as an interlude instead. But it was very much inspired by Brian Wilson indeed.

— Like “Genkin ni Karada wo Hare,” “Umibe no Futari” features another guitar solo that really leaves an impression. You sure love your solos, don’t you, Kadoya?!

Kadoya: Well, I was always a lover of fusion music, so…

— Did you have to beg the others to let you have those solos?

Kadoya: No, I’d actually prefer not to do them if possible, but I just thought guitar solos really fit those songs nicely. The only problem is that I don’t have a lot of variety when it comes to soloing, and that’s why the one on “Genkin ni Karada wo Hare” sounds like Santana basically.

— Just being able to play something like that sounds to me like you have plenty enough variety though! I had something I wanted to mention regarding the vocals on the next song, “Oyasumi Honey.” Whereas it sounded like you were singing the other songs on the album quite casually, on this song it felt like your vocals were highly emotional. Would you agree with this assessment?

Iemoto: That might just be thanks to the melody… Hmm, I’m not sure. (strained laugh) I always try to think about the lyrics and be as emotive with my singing as I can, but I’m just not very good at it. Ever since way back I’d listen to my own singing and think it doesn’t sound very emotional. I think it must be thanks to the melody that you felt the way you did — I didn’t try to sound specifically emotional on this song.

— Ah, so in your mind it’s not that you were singing any of the other songs “casually” either?

Iemoto: Nope. (laughs)

— Do you ever consciously try to change the tone of your voice in accordance with the song?

Iemoto: I do try to make it fit my image of the song, so perhaps it changes accordingly. I don’t get clear explanations from whoever wrote the lyrics as to what the songs are about or anything. I’m just told to listen to it and sing it how I see fit — although Kadoya does give me a pretty good idea of what he wants by providing guide vocals on his demos.

— I see. The last song is “Koisuru Dress.” I was first introduced to Uwanosora through hearing this song on YouTube, and the first thing that caught my ear about it were the vocals. In my mind, I felt that songs like this are usually carefreely sung by the likes of Hitomitoi or Yuumin — just crazily talented singers — but it didn’t sound like it was super easy for you.

Iemoto: “Koisuru Dress” was indeed the most difficult song. There were several parts that were very tough… (laughs) But pretty much all songs on the album were actually more or less difficult for me. Even my singer friends have told me they think these songs seem hard to sing.

— I find that really charming about your singing though — that “innocence.”

Kadoya: That’s true, yeah.

— When I first learned of Uwanosora and read that two of you were from Nara, I kind of automatically branded you in my mind as a “band from Nara.” But reading the lyrics I then began running into words like “sea” or “wind” and I just thought “wait, hang on… there’s no sea next to Nara!” I’m guessing those bits in the lyrics were the influence of Kadoya, having lived in places like Kanagawa and Yokohama.

Kadoya: Maybe. I always did like the sea and the wind and all those sorts of really vague things…

Oketa: Because they’re easy to write about? (laughs)

Kadoya: Yep. (laughs)

— When I was originally thinking about this interview, I envisioned myself posting it along with big, bold letters saying “BAND FROM NARA.” I thought it might be good to give people a clear sense that two of you are originally from Nara and that your band is active in the Kansai area. But do you feel that the “Nara label” might actually not be a great fit for you after all?

Iemoto: No, we’re fine with whatever… (laughs)

Kadoya: We can live with that.

Oketa: We’ve never made a big deal about it and we’ve never even done any activities in Nara, so there’s virtually no real connection between us and the city. That said, we don’t have anything against being called that, but we also don’t plan on making it our selling point or anything. Yeah… we’re fine with whatever. (laughs)

Interview conducted in Nara on September 2, 2014

Most CD’s and LP’s on display at Django have hand-written comment cards by Matsuta. The store offers a vast collection of city pop and related genres, so readers interested in this music should definitely head over for a visit. We also received comments regarding Uwanosora from Matsuta and a customer who happened to be visiting the store, so we’re publishing them below.

Matsuta (Django)

I’m not much of a music critic, but I really can’t believe it’s a group of fresh-faced university kids playing in a band of this quality. Their arrangements are very tasteful, the vocals are great, and I can’t complain about the percentage of amazing songs on the album either. The musicianship featured on the album is also fantastic. It’s hard to believe that this is their debut album.

Most people these days don’t have a preference for listening to full-length albums, but a culture like that still exists in places like Kyoto. I think it’s especially those kinds of cities that Uwanosora will find their listeners in. I’m really glad we now have a band like this with members from Nara.

Their album got a rave review over at WebVANDA as well, and that’s pretty great considering it was coming from someone so knowledgeable on music. Although rather than actually reviewing the album, it’s obvious Uchi wrote that text out of sheer excitement over this band — that just means it’s the kind of band and album that can do that to someone.

Lately I’ve been hooked on the fifth song on the album, “Picnic wa Arashi no Naka de.” At first I was mostly taken by the album opener “Kazeiro Metro ni Notte” and “Koisuru Dress,” but the more you listen the more you start the realize the greatness of all the other songs on the album as well. It really sounds like the 70s all over again, and like I said, it’s unbelievable that it’s such young people playing this type of music.

Regular customer of Django

I always liked them since first hearing them on SoundCloud. Hearing “Umbrella Walking” only made me a bigger fan, and then upon hearing “Koisuru Dress,” I knew I’d found something genius. At first they seemed focused on one style of music, but now they’ve really started to broaden their horizons. I love Iemoto’s falsetto and how it sounds so dreamy and so sad at the same time. I can’t get enough of it.