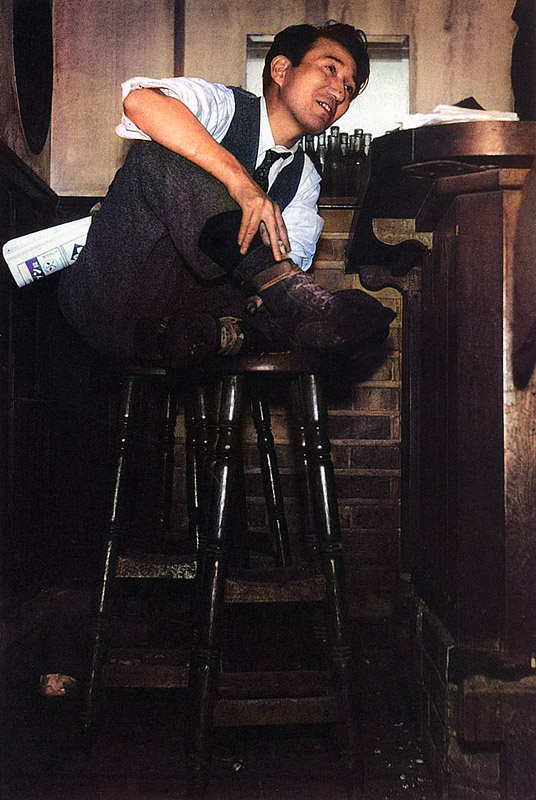

Dazai Osamu

If you’re broke but you drink anyway

Author | 19 June 1909 – 13 June 1948

“Wait here. I’m gonna go take out some money.”

One night around twenty years ago, I was out for drinks with a college senior of mine. He’d told me he was buying. And yet, he had just moments before left the establishment, leaving me behind like some sort of a sacrificial offering.

Were the same thing to happen today, I would just tell him to pay with his credit card and be done with it. But seeing as the two of us were students back then, both of us the sort of people who blew whatever money we had left and right, we didn’t carry such dangerous items with us.

I knew he wasn’t the sort of person to just abandon one of his juniors. But unfortunately, this guy was drunk. And not just drunk—he was plastered.

Would a man who was this drunk be able to successfully withdraw money from the ATM? And if so, would he be able to find his way back in his unconscious state? What if he passed out on the way? Did this man even have a clear understanding as to his present location?

I myself was three sheets to the wind as I anxiously pondered the answers to these questions.

Apparently, this senior of mine eventually came back about twenty minutes later. I say “apparently” because by that point, in addition to money I had also run out of physical endurance, and I was busy sleeping with my face down on the table. Apparently.

For some moments that followed, I gently teased him how I’d been worried I was going to be handed over to the police. I was expressing my displeasure at being left behind like that. But in retrospect, that was very shallow of me. Because in this world there are people who, in a similar situation, would leave their friend behind not for twenty minutes, but for approximately ten days.

People like Dazai Osamu.

Dazai was called a member of the Buraiha, a group of degenerates who symbolized that era in time with their anti-authority, anti-moral behavior. His representative works include One Hundred Views of Mount Fuji, Fairy Tales, The Setting Sun, and No Longer Human.

In his private life, too, he maintained an irresponsible lifestyle which included suicide attempts, painkiller addiction, and drowning himself in booze. In 1948, at the age of 38 when he was at the height of his popularity, he committed suicide by drowning at the Tamagawa Canal together with his mistress, Yamazaki Tomie. A writer with a great many fans to this very day, there even exists something called the Dazai Osamu Test.

To be honest with you, the truth is that I actually didn’t want to cover Dazai in this book simply because of how bothersome him and his fans are, but my editor told me I needed to include “someone famous” and so I reluctantly did. It might be cowardly of me as a writer to even reveal this sort of information, but then Dazai would’ve done the same. So there you go.

What I don’t like about Dazai is that compared to people like Sakaguchi Ango—someone who was also called a member of the Buraiha—I really can’t help but feel that Dazai was a rather uncool person.

He once wrote a petitioning letter—a four-meter roll of paper—to author and Akutagawa Prize selection committee member Sato Haruo, saying, “I humbly beg of you to award me the second Akutagawa Prize. Please don’t abandon me, Mr. Sato. Please don’t let my name die.”

That might still be within acceptable limits. But when he was approached at a pub by Nakahara Chuya—their first time meeting—he literally went running home on the verge of tears.

Nakahara was one seriously frightening individual, and so he followed Dazai to confront him at his house. But Dazai simply hid inside his futon, refusing to come out. Even if Nakahara was perhaps a bit lacking in common sense, it was all still rather uncool on Dazai’s part.

He was also very diligent when it came to his writing. For a period of time following the war, he rented a room separate from his residence to which he would commute after 9 AM, lunch box in hand, and work there until around 3 PM. To me that just sounds more like your average government worker than a “degenerate.”

On top of that, his tooth decay was so bad that he could only eat soft foods—his favorite foods included eel, tofu, and banana. Hey, I like tofu as much as the next guy, but I’m just saying: rather than tofu, wouldn’t a true “degenerate” mostly be seen licking salt or something, with a big bottle of booze in hand?

Still, I don’t want to make fun of the man too much. After all, degeneracy and such is all a part of a writer’s performance style.

In modern times, a Dazai Osamu who didn’t act like a degenerate would be like a Kojima Yoshio who didn’t always take off his clothes. Or like a Dandy Sakano who didn’t make bad jokes. Just like how Kojima Yoshio has to appear on TV wearing nothing but his trunks even when it’s winter, so did Dazai Osamu have to pretend like he was a degenerate even if in reality he was just a wimp hiding in his futon. The “degenerate persona” was his profession. It’s probably part of what to this day still attracts many people to him.

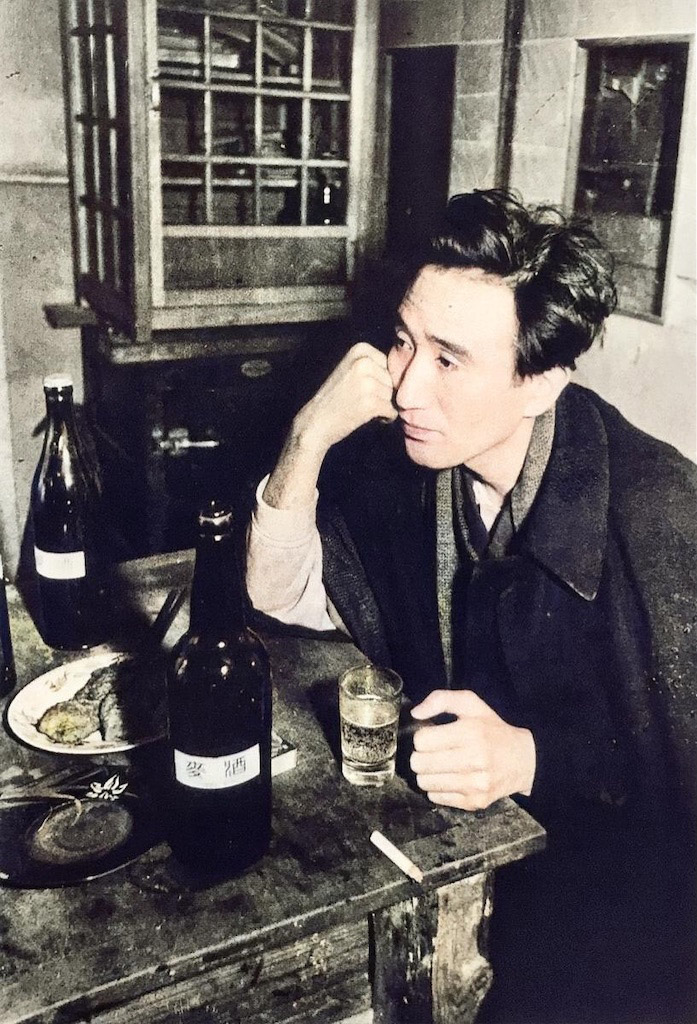

Dazai also wrote numerous essays on alcohol. While I’m not the right person to talk much about his literary qualities, I can sympathize with many of these works. In Sakegirai, he gives the following account. I’m sure the great majority of drunkards can identify with this.

At times I feel anxious and distressed, and I wish to cover up those feelings with alcohol. When I do, I go out and head to a sushi place near Mitaka Station. There, I drink my alcohol in a great hurry.

While it would be convenient to have alcohol at home in times like that, the problem is that when I do keep alcohol at home, that also makes me anxious. It’s not that I necessarily even need to drink per se, but whenever there is alcohol in the kitchen I just feel an urge to banish it completely, and so I gulp it all down in quick succession. I do not possess the expertise necessary to keep only a small amount of alcohol available for drinking when the right opportunity arises. I am just naturally of the “all or nothing” school of thought.

Thus, I usually do not keep even a drop of alcohol at home. Instead, I have developed a habit of going outside the house when I wish to have a drink. That is where I proceed to drink to my heart’s content.

That was a long quote, but it’s probably no small number of people who have abolished alcohol from their homes purely in an attempt to stop themselves from mindlessly drinking all the time.

Dazai gives a very accurate description of the emotional turmoil of the drunkard. And yet, despite what he wrote above, he would still keep alcohol at home. This weakness of his must be part of what makes him so appealing.

Writer Toyoshima Yoshio, who Dazai loved and respected, and who also served as chief mourner at Dazai’s funeral service, described him as follows.

On one hand, he was often driven to feel terribly ashamed and embarrassed. He could never manage to get one compromising word out of his mouth, instead always directly revealing his innermost feelings. This would then by reflex cause him to feel ashamed.

And to hide his embarrassment, he would drink. When he met with people, he was not able to conversate well unless it was over drinks. In other words, he would end up drinking twice as much. When meeting with him, even I would have to drink in order to make it a smooth interaction.

(Dazai Osamu to no Ichinichi)

Dazai was himself aware of this shortcoming, which he also described in Sakegirai.

Drinking allows me to cover up my feelings. It’s helpful in how it makes it so that I don’t really feel all that sorry even when I speak complete nonsense. When I sober up, however, it makes the regret that much more palpable.

For Dazai, alcohol was an indispensable relationship-building tool.

With that said, some of his behavior—like him “not feeling all that sorry even when speaking complete nonsense“—also had an enormous impact on others.

Perhaps the worst of those instances, the one that really makes one lost for words, is the “Dan Kazuo Desertion Incident.” While his entanglement with Nakahara Chuya had made him go running home with tears in his eyes, Dazai was himself likewise experienced with driving others to the verge of tears.

Dan Kazuo was a Naoki Prize-winning author, best known for his works like Ritsuko, Sono Ai and House on Fire. A quicker point of reference is perhaps just saying that he’s the father of Dan Fumi—although, in writing that, at this point I’m not sure how many of you reading this would even know who that is. (By the way, she’s a different Dan from that smiling woman in those Kinmugi low-malt beer commercials.)

Dan was himself later known as the “Last Buraiha Author,” and in his twenties he and Dazai were going on near-nightly pub crawls together.

In 1936, Dazai was staying at a hot spring resort in order to concentrate on his writing. While it is unclear how long he had intended to remain there, his stay had grown longer than originally planned. Dan was thus tasked by Dazai’s wife to deliver him his living expenses. Having been promised to also have his travel expenses covered, Dan agreed and was soon on his way.

Dan was entrusted with 70 yen, which in today’s currency would be around 120,000 yen (USD$1000). Dazai received the money from Dan, and the two headed out to a small restaurant. The owner of said restaurant was asking them, “Did you get it? Did you get it?!,” eagerly awaiting Dazai’s payment of his tab. Instead, Dazai invited the man along to a tempura restaurant. Dan recalls this event in his book Shousetsu: Dazai Osamu.

Hekigyo Manor stood on the seashore nearby.

Dazai, looking as if he’d been there before, walked right in. He made his way to the kitchen area where you had a view of the ocean. […] As I worriedly sat down, I asked him, “Are you sure about this?”

“Of course,” Dazai nodded. Not to say I’m a particularly frugal person myself, but this was a high-end restaurant of the sort I was not accustomed to. For some reason, I felt anxious.

His concerns turned out to be painfully appropriate.

“How much?,” Dazai asked.

“Thank you very much,” the man replied. “That would be 28 yen and 70 sen.”

“I knew it,” I thought to myself as I began to turn pale. Even the color in Dazai’s cheeks seemed to fade. Still, this setback did not bother us for too long. Soon enough me and Dazai sat up straight once more.

They’d turned defiant. To begin with, why would anyone feel the least bit surprised by the bill when you know you’re eating at a high-end tempura restaurant?

In any case, the pair had just burned through over a third of the money Dan had brought with him, meaning there was naturally no way Dazai was going to be able to pay his tab he’d managed to accrue from his lodging and alcohol expenses so far.

The pair sure did “sit up straight” alright. Once they got out of the tempura restaurant they immediately headed to a brothel, and the next morning they went to a pub where they spent the entire day. The following day, they did the same thing. Dazai no longer had any intention of paying his tab.

Finally, on the third morning, even Dazai realized he was in trouble and said the following.

“Hey Dan, I’m gonna go over to Kikuchi Kan’s place.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yeah,” Dazai replied. I was very worried. But I also knew we weren’t going to get out of this any other way.

“I’ll be back tomorrow… No, the day after tomorrow. Could you wait for me here?”

Dan, while worried, saw no choice but to do as asked.

A day passed. Then another. And yet another. Still there was no sign of Dazai. The proprietor of the inn was giving Dan cold looks. Unable to go out, he was forced to stay confined in his room. Some more days passed. Dan finally realized: it’s not that Dazai wasn’t coming back, it’s that he couldn’t.

Having grown impatient, the restaurant owner proposed to Dan that they go look for Dazai together. Not having the slightest idea where he might be, they figured he might’ve at least stopped by the house of Ibuse Masuji, his mentor.

So they go to Tokyo and pay a visit to Ibuse’s house. Dan asks Ibuse’s wife if Dazai had been around as of late. She gives them an unexpected reply. “He’s here right now.”

I threw open the sliding door.

Enraged, I went, “What the hell, man?! This is too much!” […] Dazai had been playing shogi with Ibuse. My angry shouting caused him to make a mess of his shogi pieces on the board.

I could notice his fingertips slightly trembling. The blood drained from his fade. Looking helpless, he seemed unable to speak.

Nonchalantly playing shogi after abandoning your friend in Atami—it was too much. Had he at least maintained his composure when he was found out, that would’ve been one thing. But the fact that he “looked helpless“… This guy really was uncool.

To make matters worse, once things had cooled down a bit and Ibuse stepped outside for a moment, Dazai actually murmured the following to Dan. There truly was no helping this guy.

To wait for someone, or to make someone wait for you… Which is more painful, I wonder?

While that might sound like a bit of a cool line on the surface, I challenge you to try saying that to your lover after you’ve stood them up on a date, or after getting drunk and abandoning your friend somewhere. Seriously, I dare you to use that line on them the following day when they’re accusing you of wrongdoing. It’s not going to be pretty.

Any way you slice it—you don’t even need to slice it to be honest—the one who has it harder is of course the person who has to wait.

And this was hardly a case of someone worriedly waiting for their husband or family member to be sent out to war or some such—it was about being held hostage until your friend settled their drinking tab!

Ultimately, Ibushi and Sato Haruo ended up shouldering the duo’s debt of 300 yen. This means that their debt had ballooned to four times the amount initially entrusted to Dan by Dazai’s wife.

Some of you might be thinking, “Man, Dazai was lame. That’s just terrible.” But he was actually able to channel what he felt at the time into a work of his, and it is a classic we all learn about in textbooks today. That work is called Run, Melos!.

While Dazai himself did not run—he simply kept sitting, not running even when they found him playing shogi—he made it so that Melos could. I suppose it’s just as one might expect of the man.

Even Dan—the person who did the waiting—would later give high praise to the work, saying, “Every time I read this work, I think about how lucky I was to have myself played even some minor role in the history of literature.”

All’s well that ends well, I guess.