This is an interview with MONO NO AWARE about their fourth album, Gyouretsu no Dekiru Hakobune, or Ark With a Line.

As far as this album goes, “Zokkon“ might be the highlight for me—as always, this band just absolutely nails the simple stuff. Calling it “simple” might be misleading, though, because when it’s simple, there’s nothing to hide behind. But MONO NO AWARE make it sound so effortless.

Interview & text: Nagahata Hiroaki (Japanese text)

Photography: Masuda Renzo, Taniura Ryuichi (some photos taken from here)

English translation: Henkka

MONO NO AWARE: Website, Instagram, Twitter

Note: You can buy Gyouretsu no Dekiru Hakobune on CDJapan.

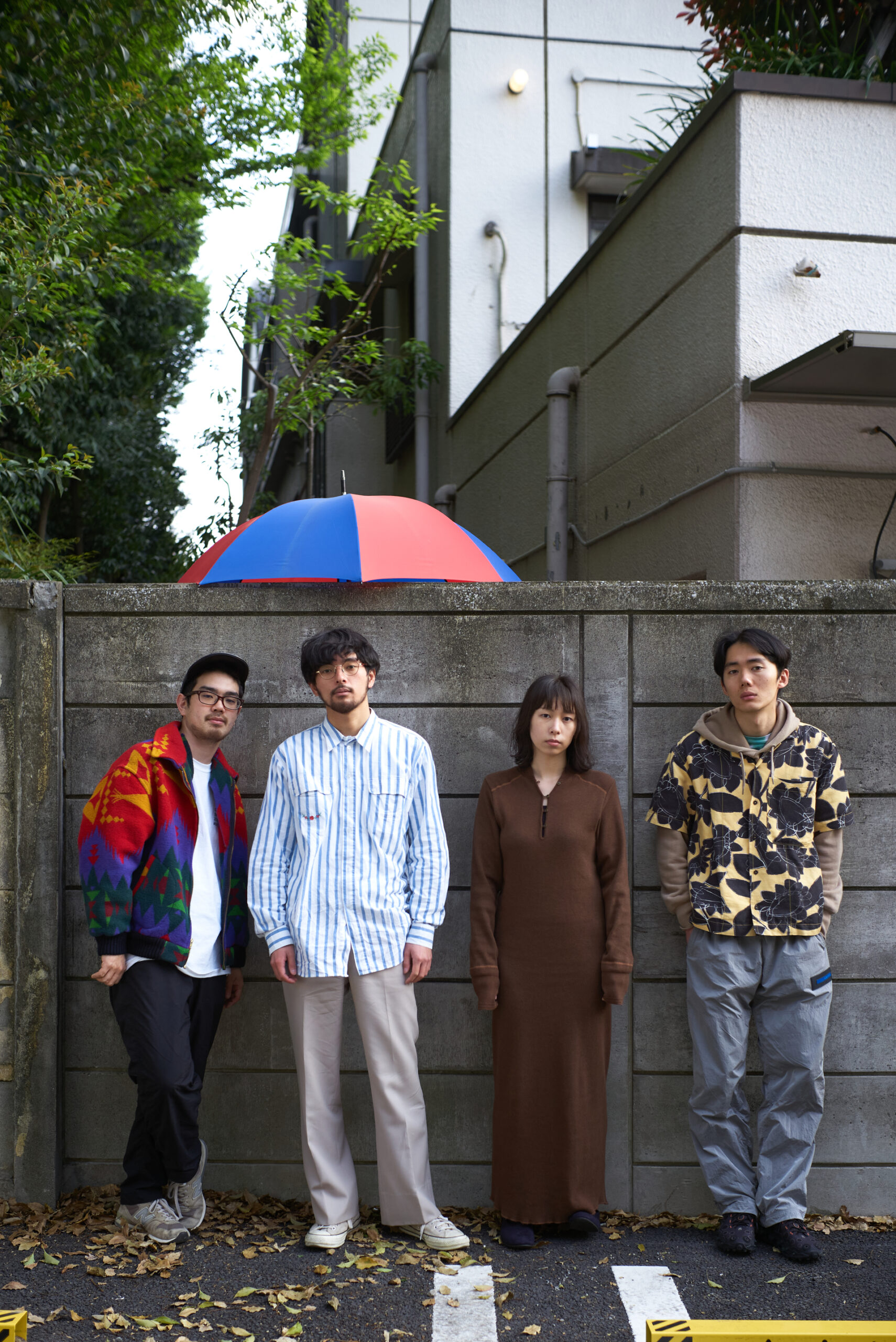

MONO NO AWARE

(L-R) Kato Seijun, Tamaoki Shukei, Takeda Ayako, Yanagisawa Yutaka

MONO NO AWARE—armed with a peerless command of language and a warm band sound, they continue to update their music while never being tied down by genres.

On 9 June, they released their fourth full-length album, Gyouretsu no Dekiru Hakobune. The album features ten songs, including “Zokkon,” the theme song to theatrical anime film The Stranger by the Beach released last September, and “Soko ni Atta Kara,” their first digital single of 2021.

In this interview, we sat down with the four members of the band to talk about the creation of this album, about conflicts within the group, and about what they think in regards to this current “mood” that hangs in the air of society today.

— I feel like this album, Gyouretsu no Dekiru Hakobune, really shows MONO NO AWARE’s strengths specifically as a band. Up until your previous record, it always strongly felt like it was Tamaoki bringing in the blueprints which the rest of the members would then construct. But this time around, it’s like the other members’ interpretations come together within the ensemble, leading to the album having a deep, natural sound. I wonder if you yourselves personally feel the same way?

Tamaoki Shukei: Yeah, I definitely get what you mean.

— Could you start by telling us which songs form the core of this album?

Tamaoki: Last year when we were approached about doing the theme song for The Stranger by the Beach, we actually had three candidates: “Soko ni Atta Kara,” “Zokkon,” and “LOVE LOVE.” (It ended up being “Zokkon.”) So when we started making the album, we already had those three songs in a nearly finished state, and we decided to record them first.

At that stage, it felt like the approach of all these songs was “love,” and you could maybe say it was those three songs from which we deducted the theme of the album as a whole.

— Did it feel like you were trying anything new sound-wise with those three songs?

Tamaoki: The two songs aside from “Zokkon” had more instrumentation than our past songs. I was running behind schedule with the lyrics for “Zokkon,” so in the meanwhile the other members were focusing on the instrumental for “Soko ni Atta Kara” without me, and that’s when the sound evolved considerably. Especially things like that steel guitar in the interlude—I was going, “Wow, this is so good.” I realized then just how great it was to hear these songs getting completed without my involvement.

— That had never happened before?

Tamaoki: No. With our past songs, it had always felt like they were totally under my control.

— Was that something the rest of you were highly conscious of?

Yanagisawa Yutaka: I was the last person to join this band, but while the previous drummer would faithfully recreate what he heard on Shukei’s demos, I wanted to take it in the direction of something that felt physically nicer to play. Basically, I always wanted to play phrases where it felt like my hands were moving on their own.

— Indeed, I do think your play style has always really stood out. But I just feel like on this album the ensemble sounds so organic, and I’m just wondering what might have brought about that change.

Yanagisawa: Sure, I hear you. I have my ego as a drummer, and I always want to craft things my own way. I had been trying to do just that since our first album, and although it had always been a blend of “things I want to do” and “things Shukei wants to do,” you’re wondering why on this album the balance has now changed. Right?

Takeda Ayako: I, too, always felt that I shouldn’t just play everything exactly as it was on the demos I was given. The problem, though, was that up until now the demos were always so fully realized that the bass lines and vocal melodies would be closely linked…

Tamaoki: Yeah. In my case, I think up the vocal and bass lines at the time. (laughs)

Takeda: But now I’ve changed my thinking on it—I don’t feel that I have to try and force myself to change anything. Because even if I’m just reproducing what I hear on the demo, surely there’s still going to be something different about it just because of my own bass playing habits. That alone should give it enough of my character.

— On that subject, what were your formative bass playing experiences?

Takeda: I always liked Thee Michelle Gun Elephant, so my role model was Ueno Koji. Back when I first joined the band, I was constantly saying, “I’d rather die than use any effects!”

Kato Seijun: I always did wonder why you were so against using effects. So that’s what it was. (laughs)

Takeda: Deep down, I can be so stubborn. When there’s no one there to stop me, I tend to stick too closely to my roots.

— Even just your “presence” alone when you play the bass is enough to make it work. In a different interview, Tamaoki was saying how, when it’s you playing, it will sound cool even if you’re only just playing root notes. Yanagisawa, on the other hand, pulls rhythms from all kinds of different genres and expresses them physically through his drumming. I feel like on this album, your various idiosyncrasies have fused together on a higher level. So with all that said, what would you say your role is, Kato?

Kato: Since around the second album, I became the one who brings the heat. (laughs) Shukei lets me handle all the solos, making it easy for all my usual playing habits to come out.

— So that’s what leads to that intense, heart-captivating sound of yours. “Soko ni Atta Kara” starts off with this chill, tropical mood, but then as it approaches the outro, there’s this surge of energy. Surely that progression is a great representation of you at your best.

Kato: The demo for that song was finished quickly, leaving me lots of time for experimentation, so I tried adding in some additional steel and acoustic guitar. When I first heard the demo I could just hear this “warmth” about it, so I figured adding some steel guitar would give it that straightforward, tropical vibe. I’m always conscious about trying to respond honestly to what I feel in Shukei’s demos.

Tamaoki: I just mentioned this a moment ago, but at the very beginning of the recordings, I remember seeing how “Soko ni Atta Kara” had gotten this huge upgrade without me even being there, and I just realized, “Wow, I’ve really underestimated the other members.” I came to see how I should be entrusting them not only with things like “make it louder” and things like that during production, but full-on arrangement responsibilities.

I’m someone who can get quite self-conceited, so this time around, I tried to hold back as much as I can and finish the demos quickly so that the others could hear them as soon as possible.

Kato: On the demo of “Soko ni Atta Kara,” he just sang the song to his own accompaniment. That way of doing things might’ve been something new for Shukei.

— Were your previous demos all programmed? I can see how there would be quite a difference in terms of a remaining “blank canvas” in just a self-accompanied demo versus a programmed one.

Tamaoki: Yes. I’d never tried making a demo before just sitting down in my room and playing something.

— Again, to me it feels like “Soko ni Atta Kara” is the song that symbolizes this album. As we discussed, the difference in approach you took is apparent in the sound, demonstrating your evolution as a band. On the other hand, “Zokkon” and “LOVE LOVE“—with the large number of words in the lyrics and the complexity of the compositions—help to preserve that “essence” of MONO NO AWARE that we all know. It feels like this album is going to be a turning point in your career.

Tamaoki: Right. I actually made the demo for “Zokkon” when I was 19. I think it was right around the time when Yutaka was about to join the band.

Yanagisawa: Didn’t we even rehearse “Zokkon” a little bit back then?

Takeda: Yeah. I think we recorded it, too.

Tamaoki: The chorus is the exact same as it was then. But as I was listening to our demo from back then, I felt that it would’ve sounded outdated had we played it exactly the same way. It wouldn’t have felt right for me. So I completely redid the arrangement, turning the song into the way it is now. It’s like Frankenstein’s monster. (laughs)

“LOVE LOVE” is another song I already had from quite a while ago. We reworked that one a fair amount, too.

— I see. So the way you make your songs can vary quite a bit depending on the song.

Tamaoki: With “Soko ni Atta Kara,” although I wasn’t particularly thinking, “I’m going to make something special,” it still turned out really good. On our previous albums I was always struggling to come up with a lead track, and looking back, there were parts that we could’ve just made more simple…

This time around, we tried it both ways—everyone making a song together with “Zokkon,” and me making one by myself with “Soko ni Atta Kara“—and thanks to that, I was able to loosen up a bit.

One clear example of something that was different is how in the past the demo titles would often end up becoming the actual song titles. But this time, I just named the demos more like… “Sea” or “Loneliness” or “Bird” and such.

— Ah. That’s very symbolic of the change.

Tamaoki: I call them “sketches,” and what I usually do is I’ll send them to the others and ask for their opinion. For example, right after those three songs we just talked about, I wrote “Mahoroba” which has this strange chord progression. When I sent that to the others with the working title of “Mysterious,” I could tell how they all totally got what I was going for with that song. They were all saying it was a good song. So now I knew that since at least 40% of the album was going to be good songs, the rest of it ought to be smooth sailing.

Yanagisawa: We recorded this album over four sessions, and “Mahoroba” was such a good song that I felt we could’ve recorded it right away, but Shukei went, “Let me think about it some more—I can make this song even better.”

Tamaoki: Right. It ran the risk of becoming this super simple ABAB form song.

Yanagisawa: At the time, I was hooked on stuff like Sufjan Stevens; this acoustic-sounding, very simple kind of music, so I actually thought it would’ve been fine as-is.

Tamaoki: I was myself listening to Sufjan a lot, but I thought it would’ve been dangerous to record it in that form. You’re the type of drummer who can take references and use them to build up your own ideas, but I’m basically just a copycat, and I like to put in stuff that I like while at the same time hopefully not making it obvious. (laughs) When you start putting this sort of quiet, atmospheric stuff into a song, you risk making it sound overly simplistic and underdeveloped.

Yanagisawa: Right.

Tamaoki: So for me, I was thinking to give it a structure like Radiohead‘s “Paranoid Android,” but then it ended up becoming something completely different. (laughs) With the lyrics, too, I already said everything I wanted to say in the first couple of lines, and then I just I felt like it didn’t need any more lyrics after that.

— Yanagisawa seems like the type of person who is proactive about incorporating into your music elements of whatever he’s currently listening to.

Yanagisawa: Yeah, I’m pretty much a trend chaser. I have a thirst for knowledge—I want to know what the people around me are into and why. Some people like Sakamoto Ryuichi are the opposite in that they’ll think, “If what I listen to is going to have an influence on what I make, then I’m just not going to listen to anything at all while making it.”

— I get the feeling that your trend-chasing habits play a big part in your music having so many different moods and not being limited to just that band sound.

Kato: I love when Yutaka talks about this kind of thing. I really do. (laughs)

— By the way, what else were you listening to during the recordings for this album?

Yanagisawa: I can tell you, but it’s going to be a bit of a spoiler… (laughs)

Well, with “Yuureisen” for example, on the demo the rhythm was just this reggaeton loop, and then I started adding different percussion sounds on it with the intention of it not being just a simple drum sound.

For a time, everyone was always trying to just recreate programmed drum parts using live drums, but I feel like that’s missing the point… What I was trying to do was to record those programmed-sounding parts while at the same time having the drums sound like real drums. That is, I wanted the sound to convey the appeal of the actual instrument itself. Uhh… I’m afraid this might be getting a little technical… (laughs)

— That’s fine—this is important information for understanding the songs on this album.

Yanagisawa: On that song, the snare sound—which is the main component of the drums—was overdubbed. That’s something I wanted to try doing in order to take this world thought up Shukei and make it even more musically interesting.

Another thing is that in the chorus—the so-called “peak” of a song—I didn’t want to use a ride cymbal. So instead, it just starts with a quick hi-hat hit, and during the chorus I changed up the bass drum pattern and stacked up different snare drum patterns to sort of signify how that was the climax.

— That’s that “band magic” right there. So rather than it being Tamaoki building these musical worlds from scratch, it comes across as more like him translating the human world into music form. That makes it all the more important for the other band members to pick the right sounds with which to express themselves, and I feel like what you were just talking about gives us a glimpse into that process.

Yanagisawa: Maybe it’s exactly for that reason that we never share between us our exact intentions behind the things we do. We’re all pretty “dry” in that sense. (laughs)

Kato: I mean, it’s just too much. It’s not something you really feel like talking about…

Tamaoki: If I started telling you guys about like the kinds of images I have when I’m writing my songs, we wouldn’t have time to ever get anything done. (laughs)

— While we’re on the topic of “Yuureisen“… To me, that is the best track on the album. “Leaping off the ghost ship / In a world where I’ve lost even the will to swim / It feels like I’m dreaming“—this line has got such a disquieting air to it. I feel like it’s connected to the following song, “Mizu ga Waita,” and the line: “It’s a festival, it’s a festival!” Is this, to put it bluntly, about the modern dystopia?

Tamaoki: Yes, that’s right. By way of COVID, society last year was at least making merry about the “new normal” and all that. But now, this year, it’s just gotten to be so gloomy. So because of that, it felt like timing-wise it would’ve been tasteless to do songs about the more “traditional” dystopia. I think it’s maybe similar to how Miyazaki Hayao stopped making works like Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind. In other words, the message isn’t, “Everything is in total ruin,” but more like… “I just feel kind of anxious about things.” How to work with those kinds of thoughts as the motif.

At the same time, I didn’t want it to sound pessimistic either—I wanted to convey it in an impartial way; in the sense of, “This is just normal.” Sound-wise, I wanted it to sound SF-esque, like the Arctic Monkeys‘ sixth album (Tranquility Base Hotel & Casino). That was such a cool album.

— You sort of have this stance of never allowing yourself to wallow too deep in that sense of despair, don’t you?

Tamaoki: Yeah. Because if I started writing songs that were all like, “I’m all alone in this tiny apartment, drinking canned beers,” I’d probably get so immersed in that world that I’d never be able to get out of there. (laughs)

— In that sense, another song that’s included on this album, “Kodoku ni Natte Mitai” (“I Want to Be Alone“), captures a very subtle sort of nuance. There’s a really well-done contrast between the song’s joyful sound and the surprisingly serious lyrics, showing this sort of humor that isn’t mere wordplay. It’s almost as if it’s saying how the more serious you happen to be feeling, the more it can kind of look funny from the outside. To me, this adds yet another layer of charm to MONO NO AWARE.

Tamaoki: As I was writing the song, I was thinking to myself again about how great Yura Yura Teikoku‘s “Hollow Me” is. I bet there are so many people out there who are still hooked on that song even now.

As long as the politics of today don’t change, many people are forced to live this empty sort of existence—it’s kind of become the new standard. But on the flip side, the word “empty” can also be used to describe things like escapism and nostalgia. People say they “feel empty inside” when they’re tired, but I feel like there are better words for describing that mental state. What I’m trying to say is: I feel like “empty” describes a more complex frame of mind.

— Did something happen that drove you to feel that way?

Tamaoki: Just the struggle of making this album. Everyone around me was trying to help, but even that just felt exhausting to me—I was in such a state that I didn’t even have the energy to respond to their concern. It got so bad that there was even this air of, “Wow, I guess that’s it for the band then.”

It was right around then that I was singing “Kotoba ga Nakattara” in the studio, crying my eyes out with the other members looking horrified. (laughs)

Kato: Ah. I remember that.

Tamaoki: On the other hand, a desire for solitude is such a first-world problem. That’s another way of looking at it. Those two contrasting thoughts are what led to “I Want to Be Alone“—I like how that’s quite a modest way of putting it.

Of the people who at one point in their lives sought solitude, some people like Jack London ended up committing suicide, while others ended up going back to where they came from. There’s not a lot of people who can actually pull off being alone to the very end. I feel like once you experience being alone, that’s when you truly come to appreciate the people who are there by your side.

— During the self-isolation period, while it felt like a lot of people were emphasizing “solidarity,” others were talking about how they actually liked having more alone time. Personally, I didn’t know what to think about how… “ambivalent” it all felt. Here, you were focusing on the feelings of the latter group.

Tamaoki: Remember how there was the whole “#utatsunagi” hashtag trending on social media? I was myself tagged by an acquaintance. But when I tried passing it on to some of my very few friends, Ryoto (from Tempalay) and Hikaru (from domico), they both turned it down like, “Wait, what? You’re actually into that sort of thing? Sorry dude, I’m gonna pass.” I felt down about it. “Man, what am I even doing…?”

But at the same time, I came to realize how, deep down, I don’t actually believe that music is some tool meant for saving people. That’s when I lost the will to try and somehow appeal to the world about how self-conscious I am. What I wanted to do was to write a song in which I could express certain feelings that you can’t speak out loud in this current climate.

— A moment ago, you were talking about how communication within the band can be surprisingly dry. I wonder: does the rest of the band agree with Tamaoki’s sort of emotionally detached mindset? Because somehow my feeling is that you might…

Takeda: Mmm… I think so, yes.

Yanagisawa: I don’t believe in that word either—”solidarity.” If anything, I’m more the type of person who’s inclined to immediately visualize the people who can’t show solidarity.

Aside from music, there was also that book recommendation hashtag, right? I didn’t like the idea that you had to be “tagged” if you wanted to recommend a book to people, so I decided to just make up a hashtag of my own and introduce some books, and no one at all joined in. (laughs) I’m just so totally against anything that feels elitist.

Kato: For me, I dislike the entire concept of “solidarity,” so I just ignore everything about that sort of thing. It’s the same thing as with complexes. Like… “Hey, your inferiority complex is catchy—maybe we can turn it into an advertisement!” I don’t believe you can save everyone, so I just give up on even trying. But Shukei, being the expressive person that he is, takes it upon himself to keep trying. I really admire that about him.

Tamaoki: I wonder about that… Like, I’m definitely someone who’s mistrustful of people. But even so, I guess I don’t want to give up on them either.

— Would it also be fair to say that you were aiming to portray the “natural state” of emotions on this album? Because if so, that makes the natural sound of the instrumentation that much more fitting.

Tamaoki: Yeah. Seijun uses that word a lot—”natural.”

Kato: Guitar-wise, though, I really wasn’t trying to give it any particular “sound.” So if the songs do sound nostalgic or whatever, they just happened to turn out that way on their own.

Tamaoki: Also, this album was made in the order of the initial sketches of the compositions, followed by the instrumentation, and finally the lyrics. So a part of it could be that I just happened to pick the words that felt natural for the songs constructed by the other members. That’s why we stopped relying on Japanese-language wordplay on this album.

— That reminds me: your singing on this album is so relaxed. It sounds so different. I feel like it’s more a part of the overall sound now. I heard that, for this album, you recorded your vocals at home. Was that maybe the reason?

Tamaoki: I recorded them in my isolated house, in a six-tatami mat room with paper sliding doors directly in front of me, so it was a 180-degree difference between that and the recording studio. Equipment-wise, while I did use an expensive mic and preamp that I borrowed, for the audio interface I just used this beat-up Zoom R8—the engineer said it was as if I was “using silverware to eat off of an Anpanman plate.” (laughs)

I’m someone who’s quite attentive to others, so when I’m singing in the studio, I’ll end up going shirtless just for the sake of the performance.

— Performing for your bandmates? (laughs)

Tamaoki: There’s a small window in the recording booth from which they can peek through. (laughs)

This time around, there wasn’t anything like that—at home, I was mostly sitting down to record. I forgot about everything I’d learned in voice training, and things would happen as I was recording… Like, I’d notice the mic stand sliding down as I was singing and I’d be chasing after it with my mouth while singing, but if I was happy with the take, I’d just keep it.

— You saying that makes me recognize again how—as you were just saying yourself—this was an album that really pulled out your genuine, innermost feelings. It’s not mere “clever wordplay.”

Tamaoki: I didn’t want to just twist some words around as to say, “Hey, here’s this other way of looking at things.” I wanted to explain why one needs to change the way they look at things, and as a songwriter, that’s something I have to deeply understand myself.

Moreover, I’m trying to express something that can’t be relativized. You can try and tear into old values with this counter-culture sense of like, “Hey, here’s a new way of thinking about things!” And that can have its place. But eventually, that new way of thinking, too, is just going to be hijacked by some outside group.

— That ties into what Kato was saying earlier about how inferiority complexes can be turned into advertisements—just as long as they’re “catchy.”

Tamaoki: Exactly. That’s why, rather than just throwing my ego out there, I tried taking more of a broader, bird’s-eye kind of view. Today’s society is too connected—every time anyone tries to talk about solidarity, someone still ends up feeling hurt and left out.

For me, my goal, the thing that I’ve been pursuing all along, is this state where we’re all separate, and yet… A state in which we don’t ignore one another.