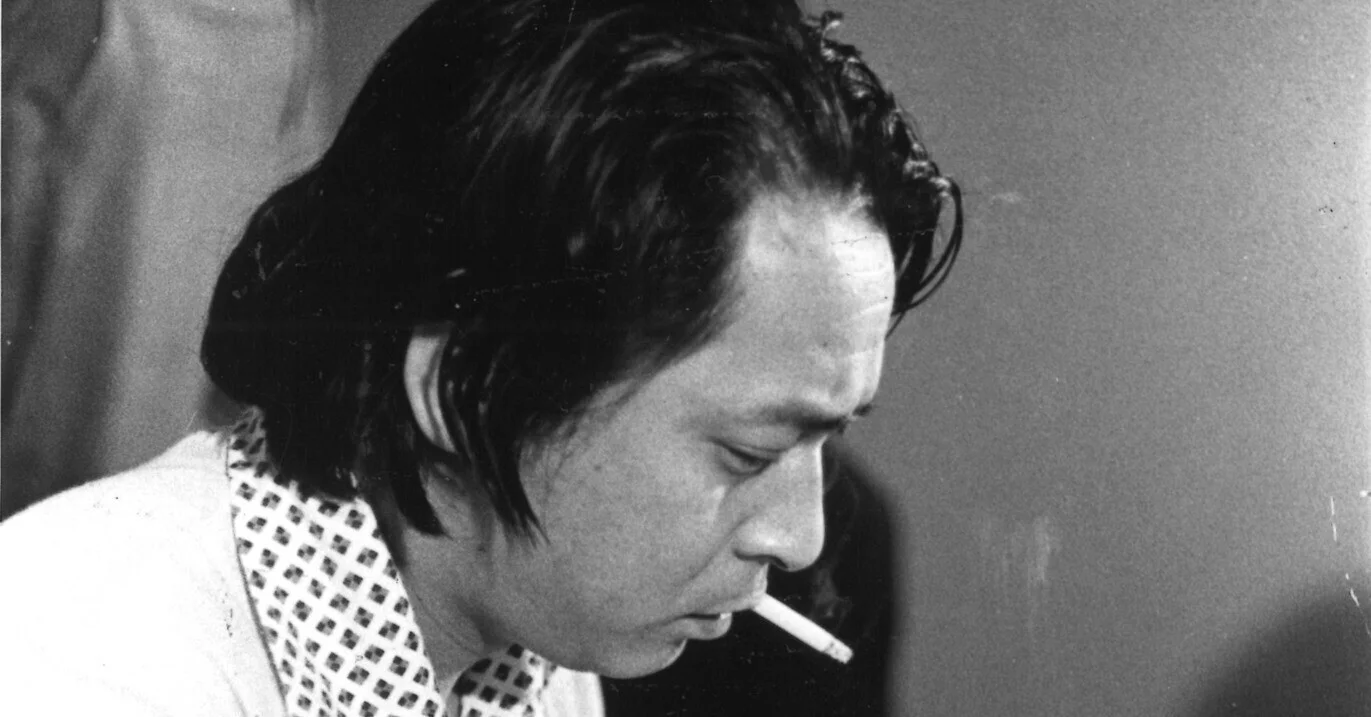

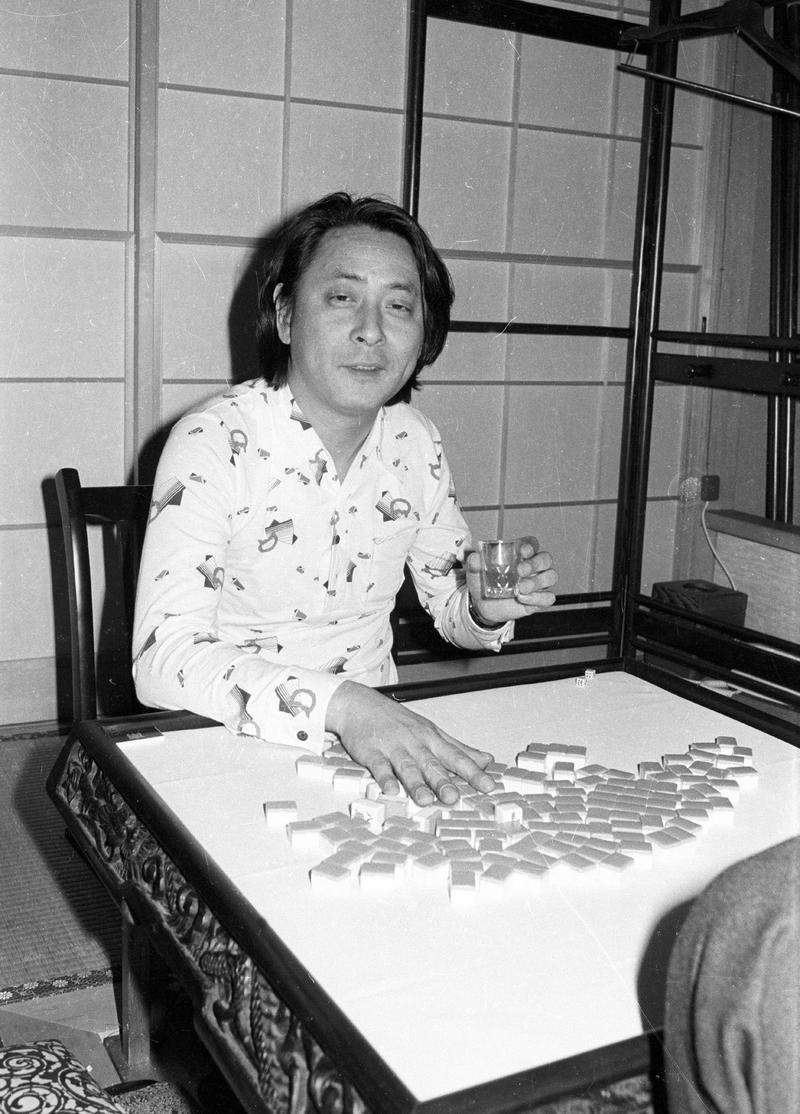

Kojima Takeo

If you’re broke but still you drink anyway

Mahjong player | 11 February 1936 – 28 May 2018

How to drink when you have no money?

This is a major dilemma for the destitute salaryman. “Just sit still and don’t go drinking then.” “Why not just drink at home?” If these were viable options, it’d be a non-issue to begin with.

Listen, we’re not asking for the world here. We’re not asking to be in Ginza drinking bottles of Rémy Martin, or that it has to be literally Igawa Haruka fixing us highballs at the counter.

But hell, it’d be nice to at least get to drink some draft beer in some back alley that reeks of piss. We simply want some cloudy sake to make our minds cloudy, too. Sometimes it gets old just drinking chu-hi’s and watching YouTube videos, you know?

You work and you work, but you just never seem to have any money. You save and you save, until finally you have enough that you just might be able to go out drinking. But even if you did, what’s the use? It would only feel suffocating. No wonder you feel miserable—under those circumstances, even great men would be staring into the palms of their hands in despair. Just what is one to do?

When life’s got you feeling down like that, just knowing how Kojima Takeo—”Mr. Mahjong” himself—lived his life, it might inspire you to go out drinking even when you don’t have the money to do so.

Surely there’s no doubt that there are now considerably fewer people who enjoy mahjong as a pastime. Even in places like Shinbashi—the “salaryman’s town”—work buddies sitting around a mahjong table has become a rare sight. In the past, it was even said that not being able to play mahjong would hurt your career prospects as a salaryman. Echoes from a different time.

According to data gathered by the Japan Productivity Center in Leisure White Paper 2018: The Current Status of Leisure and Industry/Market Trends, there were five million mahjong players in 2017, less than half of the 13.5 million players there were in 2009. According to the Japan Crime Prevention Association, there were nearly thirty-five thousand mahjong parlors operating in 1977. By 2017, that number had dropped to nine thousand.

Mahjong was at its most popular in the 1970s. Night after night, lines to mahjong parlors stretched out into the streets. Right in the midst of this mahjong boom, Kojima Takeo was appearing regularly on the popular late-night show “11PM” and mahjong segments on other TV programs, making a name for himself as a “mahjong personality.”

Kojima’s emergency was in large part thanks to the backing of Asada Tetsuya (aka Irokawa Takehiro) who had captured the hearts of young people in the film Mahjong Horoki in which he was portrayed as the “Mahjong Saint.”

Born in 1936, Kojima was a Hakata native. He graduated from junior high school, apprenticed as a pastry chef, and then began working as a mahjong parlor office boy. In his late twenties, he moved to Tokyo, got a job at another mahjong parlor, and made his living working as the manager there. Around the same time, he took part in a famous mahjong tournament, winning the championship out-of-the-blue and thus making a name for himself.

It’s at that mahjong parlor where he became acquainted with Asada Tetsuya. His book Shousetsu Asada Tetsuya contains a story celebrating Kojima’s “talents.”

He was your stereotypical man of debauchery. Drinking, gambling, prostitution—he was lacking in no area. In fact, it’s difficult to imagine anyone being as thorough in their dedication to drinking, gambling, and prostitution.

A complete dedication to drinking, gambling, and prostitution. In a perfect world, people would be singing his praises. They’d call that a hat trick!

Helped by his innate optimism and lovable character, Kojima then became increasingly active as a TV personality. In his book Legendary Good-For-Nothing Mr. Mahjong: 75 Rascally Years of Alcohol, Women, and Money, Kojima writes:

In my life, alcohol, women, and gambling have been my everything. From the time I was young up until this very day, I have never been interested in anything else whatsoever.

It’s tough to say whether that is a desirable life or not. In any case, even among his three favorite things—drinking, gambling, prostitution—Kojima was especially fond of drinking.

Ever since I first started drinking, I do not recall even one day when I didn’t have at least a sip of alcohol. It didn’t matter if I had a cold or if I was hospitalized, if my mother died or if my father died—I was always pouring alcohol down my throat. […] On days when I had no plans, I would drink from morning till night.

He would yield to nothing. Rain, wind, or the common cold—nothing could stop this man from getting pickled. No matter the circumstances, Kojima would continue to drink.

Even as he got older, this debauchee simply kept on going. In his final years, after drinking himself unconscious with five or six highballs, he fell over while trying to get into a taxi and broke his collarbone in the process. And yet he still hadn’t learned his lesson as he just kept getting his drink on.

One might worry that he was perhaps drinking too much. But in Good-For-Nothing, he declared as follows.

People always say you should “drink responsibly.” But I actually think it’s the opposite.

It’s better to get totally blitzed; to absolutely drown yourself in booze. Otherwise, why bother putting alcohol in your system in the first place? […] Indeed, when you get absolutely piss-drunk, your body is in terrible condition. But the strange thing is that it also makes your fears fade away. Suddenly, you find yourself amazed at how full of courage you feel!

The latter part of his description has a rather alarming air about it. What he seems to be implying here is that anything is possible as long as you have spirit, and if you don’t have any spirit, you need only to drink to gain some.

I feel like we might not wish to linger on this point for too long, so let us just move along.

Kojima was now a major mahjong personality. He was flying high. However, that didn’t mean that his financial affairs were always in order.

While he drank non-stop, he considered it “stingy” to be just sipping sparingly at home. Instead, he took great pleasure in drinking 300,000 yen (USD$2,000) bottles of Rémy Martin at high-end clubs with pretty young ladies. No matter how much money he had, it was never enough.

Forty years ago, Kojima’s yearly income was 30 million yen, and yet he has said he was spending 100 million a year in places like Ginza and Roppongi. The numbers don’t add up. So how was this possible?

According to Kojima, “The good thing about high-end clubs is that you can drink there even if you don’t have any money.” Tab systems, you see.

He was proud of the fact that he could walk in and out of a club, never having to take out his wallet. Although, of course, even if he didn’t pay right away he would still have to do so eventually. In fact, it was apparently a regular occurrence for him to be unable to pay his whole tab in one go, having to ask to pay in installments.

Being able to walk into places, not a care in the world despite having unpaid debts—that’s the Kojima Style of doing things.

Kojima says that if you beg and say you only have 30,000 yen (USD$200), that is enough to allow you to drink at places where it costs 50,000 yen even just to sit down. He would say, with a smug look on his face: “The mamas prefer the 30,000 yen right now over the promise of 100,000 yen months from now.” For a man who says he “hated stinginess,” Kojima sure could be a bit of a stingy guy himself.

But the Kojima Style can be implemented outside of high-end clubs, too.

Once, when he was still a college student, Baba Hirokazu—who also later became a professional mahjong player—was taken out to a sushi restaurant by Kojima. Baba was excited as it was his first time at a “non-conveyer belt” sushi restaurant. They ate and they drank, and their bill came to 32,300 yen (USD$215).

Kojima said, “Here’s 2,300. So I owe you another 30,000. Righty-ho.” He only paid the 2,300 yen and left the establishment. It should be noted that Kojima was by no means on the wane at this time—to the contrary, he was at the peak of his career. When he’d win a mahjong tournament and receive his prize money, he would take his personnel out drinking, regularly spending a million yen (USD$6,700) in one night.

Now, I can hear the salarymen among you objecting. “What help do you expect me to glean from stories about high-end clubs and non-conveyor belt sushi restaurants?!”

Well, I believe the thing one can learn from Kojima is this concept of how nothing good will ever come to you from trying to accumulate money.

It’s one thing if you’re a wealthy person. Money begets money, and your fortune grows exponentially. But if you’re a mere salaryman, even if you spend your entire life trying to amass wealth while working yourself to the bone, it still won’t amount to all that much in the end. Is a life like that even enjoyable, I wonder?

In Kojima’s case, emotional leeway seemed to make him overly defensive in his profession. To combat this, he says that going out to drink and to have fun is what gave him vitality, and that for him it paid off many times over.

I’m not saying you should be wasteful, but I am saying that using your money freely on your passions is without a doubt also linked to one’s sense of work fulfillment.

In other words: if you want to go out for a drink, go out for a drink. Don’t worry about it even if you don’t have the money. Go to that bar you always frequent, and throw yourself at their mercy. Tell them you only have 3,000 yen (USD$20), and see if they’ll let you eat and drink reasonably well even for that amount of money.

Who knows, perhaps the ability to build such relationships is exactly what determines whether or not you’re going to live a happy life.