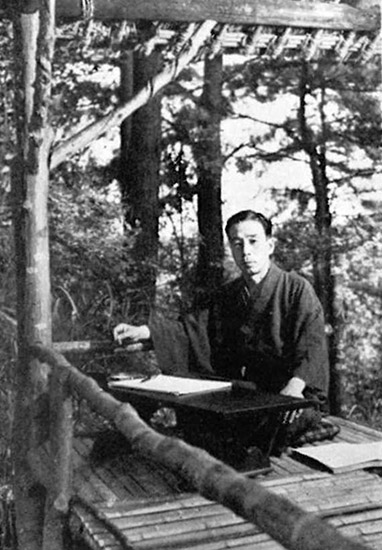

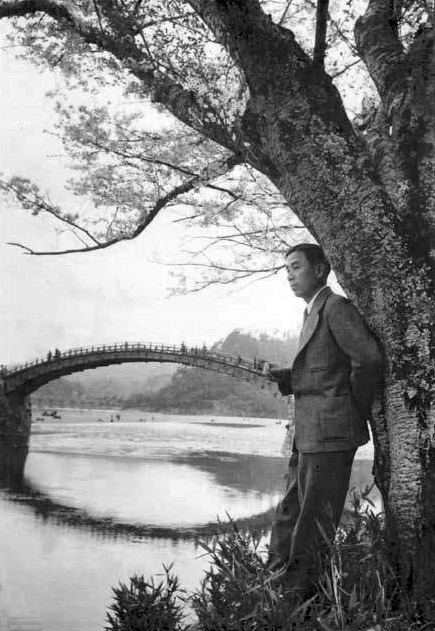

Kawakami Tetsutaro

If you wake up in police custody

Critic | 8 January 1902 – 22 September 1980

Each time the New Year holiday season rolls around I’m always deeply concerned, not knowing when I might find myself waking up somewhere unfamiliar. What with it being the season of drinking parties, there is an exponential increase in the likelihood of me getting slobberknockered.

Drinking in Ikebukuro, yet finding myself at the foot of Mt. Takao the next morning. Feeling a little lost in thought on the JR Yokosuka Line between Chiba and Kanagawa, then wondering how I managed to end up in Zushi of all places. Drinking out in Otemachi, but somehow ending up falling asleep on the streets of Shibuya.

And, of course, you always miss your last train. As someone living in the suburbs on a meager salary, not only is it hard on the wallet but it’s also mentally and physically draining.

In times like those, I like to remind myself of a certain person and it always makes me smile. A person by the name of Kawakami Tetsutaro.

The 21st century youngsters among you might be thinking, “Who the hell is that?”

Well, Kawakami Tetsutaro was one of the biggest literary critics of his time, comparable to Kobayashi Hideo, another big name from the same generation of critics.

Born in Nagasaki in 1902, he became acquainted with Kobayashi Hideo while he was a student at the Faculty of Economics at the Tokyo Imperial University (now: University of Tokyo), after which he began his critical work. After the war he was awarded the Japan Art Prize, and he was himself an Art Academy member as well as a Person of Cultural Merit.

In 1942, the year following the start of the Second World War in Japan, he served as the moderator of a symposium called “Overcoming Modernity,” featuring thirteen all-star controversialists of the time, including Kobayashi Hideo, Nishitani Keiji, Kamei Katsuichiro, and Moroi Saburo.

The theme of the symposium was “overcoming Western modernity.” The participants discussed what Western modernity was, the merits and demerits it had brought to Japan, and where Japan might be able to overcome the contradictions which it posed. Their conclusion was that American-style individualistic values—which the country had been oriented towards ever since the Meiji era—were now to be rejected.

In the Bungakukai magazine, which recorded the symposium, Kawakami was quoted as saying:

How muddy; how unpleasant the disordered gloom of peace compared to the purity of war!

A pretty questionable remark, looking back. In fact, after the war he was denounced as a warmonger.

But of course, to us drinkers, such matters are of no importance.

Kawakami, the spirited critic. The story of his that most broadens the outlook for us tipplers is the time he got in trouble with the police. I wrote above how he was comparable to Kobayashi Hideo, and one could say that the pair were in an equally close-fought competition as to who was the worse drunk.

So far, I’ve never been put in lockup. But the other day, I had my first experience spending some time in a police facility called the “drunk tank.”

Kawakami writes about this experience in his essay My Drunk Tank Chronicle. That’s a term you don’t hear much these days. The “drunk tank” mentioned above refers to a holding cell provided by the police in which they protect and detain drunkards.

So why was he put in protection?

While Kawakami’s recollection of the events is understandably hazy, he says he had been drinking red wine in Ginza when he ran into a friend of his, helped himself to a bottle of brandy which had been supplied to him, and blacked out. Next thing he knew, he was waking up on a police station linoleum bench.

That right there is your quintessential “drunk.” No more, no less. The details of how he got obliterated are so picture-perfect, I just want to applaud him. Making all these clever remarks about “modernity,” “overcoming,” and “the meaning of war,” when in reality he was just another boozer! The Shinbashi salarymen would all be welcoming him back with hip hip hoorays!

Man, enough with “Kawakami.” I’m going to start calling him by a friendlier nickname. Let’s just call him Tecchan.

So, how do you suppose “Tecchan” reacted upon awakening at the police station?

Under those circumstances—having injured his face and lost his wallet—an ordinary person might feel a bit flustered, dumbfounded, or perhaps too embarrassed even to speak. But the great thing about Tecchan is how he could always remain exceptionally collected.

His younger sister and her husband who lived nearby came to pick him up. On their way home, Kawakami gave them his rather curious report on the experience.

The policemen there were so nice, they were like hotel bellboys.

True, they had protected his safety and had courteously even phoned his family to come pick him up, so I suppose in a sense everything had worked out in this drunkard’s favor. But comparing the officers to “hotel bellboys,” that’s so novel that even his sworn friend Kobayashi Hideo would’ve been at a loss for words. Tecchan had finally pulled off “overcoming modernity”—even if at the cost of his memories from the previous evening.

Although penniless, as he was leaving the police station he said, “To express my gratitude for everything you have done for me, I’d like to make a toast with you all. Do you know where I might be able to procure some whisky?”

He was being strangely considerate to the officers, even wanting to give them gifts. One has to admire this degree of thoughtfulness—even if in the same breath you also want to ask, “You’re still going to keep drinking, Tecchan?!”

While the intellectual types can occasionally seem characteristically out-of-touch with the real world, it’s no exaggeration to say that Tecchan elevates it to a point where as a reader I really don’t even know what to say.

Even his own retelling of the events to friend and critic Yoshida Kenichi (son of former prime minister Yoshida Shigeru) is so tone-deaf it just makes one want to go, “Bravo!”

As Tecchan finished recounting his experience, Yoshida—somewhat perturbed by what he had just been told—said, “Well, I’ve heard that in the past, aristocrats who went to jail in Bastille were allowed to bring along servants and cooks.” (A rather peculiar response, but okay.) Tecchan’s response? “Could they bring women though?”

Sheesh, this guy…

By the way, Yoshida Kenichi was himself known among friends for his outrageous drunken antics. But back in the early years of the Showa era (1926–1989) when he had only just come back from studying in the United Kingdom, he was not yet accustomed to alcohol. Author Oka Shohei remembers:

He’d just returned from Cambridge, and of course he’d never had a drink before then.

So as we were drinking at this filthy bar out in Ura-Ginza, it was only to be expected that he’d suddenly start feeling sick. But when he did, he simply kept seated in his chair as he began throwing up, projecting his vomit in all directions like a water fountain, making a right mess of his face and his clothing.

(“Kobayashi Hideo“)

That is such innovative behavior, one might mistake it for British dinner party etiquette. That’s a friend of Tecchan’s alright!

This “waking up in a drunk tank” episode tells us that Tecchan, aka Kawakami Tetsutaro, possessed the mental fortitude necessary to not be fazed no matter where it might be that one comes to.

But it also suggests a need for the ability to alter one’s mindset when confronted with unforeseen circumstances. For instance, the sort of flexibility that lets you re-conceptualize “waking up in police custody” as merely something akin to “waking up in a hotel room.” That skill is what will allow you to abolish all those feelings of distress. (Well, maybe that’s asking too much…)

With that said, trying to follow Kawakami’s example by going in to catch a bit of shut-eye at the police station only because one’s missed their last train, that’d be quite an ask. “Drunk Tank Chronicle” is one thing—I don’t want to have to write my own “Lockup Chronicle.”

In doing research for this manuscript, I was surprised to learn Kawakami’s age when he was put in the drunk tank. He was 70 years old.

Incidentally, after getting boiled-as-an-owl and being detained in said drunk tank in August 1972, he was selected to be a Person of Cultural Merit a mere two months later. While it was a more idyllic period of time to be sure, giving a drunk like him the recognition of Person of Cultural Merit was a rather astonishing thing even back then.

Kawakami himself commented on the matter in the October 28 issue of Yomiuri Shimbun.

Giving an award to a carouser like me who was just thrown in the drunk tank, Japan sure is a surprisingly sensible country. Ha ha ha!

You can say that again, Tecchan. I can’t be the only one who’s thinking, “Good job, Japan!”

Now, while we all wish to be like Kawakami in that we hope we can keep drinking ourselves silly even at the age of 70, the fact is that these days you couldn’t wake up in a drunk tank even if you wanted to.

While the Metropolitan Police Department used to have dedicated drunkard shelters, the last one was closed in 2007. During the “Golden Era,” over ten thousand drunks a year were being detained in four different locations within the Tokyo area. But by 2006, that number had dropped to only around 500.

In 1972, the year our Kawakami was thrown in the drunk tank (Toriizaka Shelter), the number of drunks admitted to these drunkard shelters was 12,798—the highest figure ever recorded.