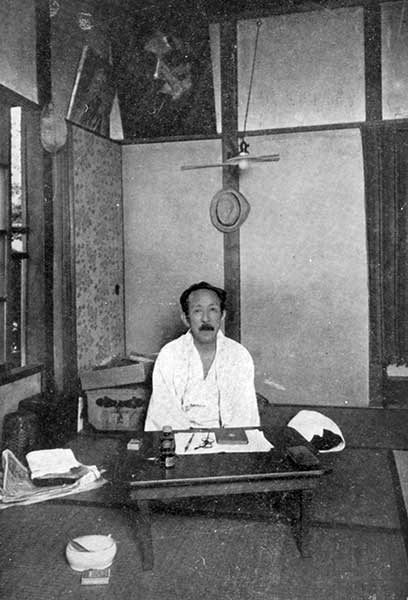

Tsuji Jun

If your coworker jumps off a roof

Author | 4 October 1884 – 24 November 1944

I’m sure many of you have experienced that feeling when you’ve had too much to drink, and then, suddenly, you feel like you could literally do anything.

While it goes without saying, that feeling is of course but an illusion. And yet, the majority of booze-related troubles and gaffes are brought about by this simple misunderstanding.

Drinking can’t turn you into a superstar—at the end of the day, an office worker is still but an office worker—but it can change the way you think and behave. Your department chief, that one Average Joe who’s always going, “Oh, I’m no Ichiro, I’m just a nobody,” who happens to like baseball? If he were to turn into a serious binge drinker, it might get him to start copying Ichiro by eating curry for breakfast every morning and practicing his bat-swinging skills at the office.

Or, well… He might start not coming to the office in the first place.

Shishi Bunroku, popular Showa era writer whose works have recently been reissued one after the other, wrote the following in his essay Drunken Confessions.

Drinking when I was young, it felt like I had twice the stamina I normally did.

Suddenly getting the urge to start running, when I actually did so, I was extremely fast and I never ran out of breath. My physical strength had doubled.

One might point out that if the above was really true, all athletes everywhere would just be drinking themselves silly before training.

But then one should not expect rationality from imbibers to begin with. Your speed and physical strength have doubled! (It feels like they have anyhow.) That is exactly what we think when it’s 9 PM and we’re at the Shinbashi Steam Locomotive Square going, “I can do anything! Anything! If I wanted, I could make this train start running again and take me home!”

Shishi also wrote this.

Climbing up to the roof of the waiting room, standing there under the glistening moonlight, I looked over to the roof of the adjacent building and I thought to myself, “If I was to try right now, I’m convinced I could make the jump across.”

I understand the feeling. When I drink, I also get the urge to jump over to the building across from my place.

Estimating the distance, I use my liberal arts brain to think about how high I would have to jump in order to make it. But then either my calculations are wrong or my feet are too wobbly or something, because when I do a practice jump from the corner of my apartment over to the balcony, I can’t muster up nearly enough speed. Ultimately, it all just starts to feel like too much of a hassle and I never get to actually making the jump for real. But dammit, I do understand the feeling.

Unlike me and Shishi, however, there is one historical figure who got drunk and actually did jump. This person was Tsuji Jun, a Dadaist of the Taisho era.

Tsuji Jun is one of those literary figures who is hardly ever spoken about in today’s literary history. When he does get mentioned, it’s usually only in passing to note that he was the ex-husband of Osugi Sakae’s partner Ito Noe—sort of in the spirit of, “A friend of a friend of my older sister was a celebrity.”

Originally an English teacher at a girls’ school, that is where he met Noe, laid hands on her, and resigned from his position in order to settle matters. Suddenly left with nothing to do, he wound up just wandering around for a while.

But since he was gifted with languages, he then began doing translation work. Tsuji is best known for his translations of Max Stirner’s The Ego and Its Own and Cesare Lombroso’s The Man of Genius. (Well, I say that’s what he’s known for, but these days nearly no one has actually read these works. Most people have never even heard of them.) The Man of Genius was the first book to shed light on the medical differences between genius and madness, and it’s this book that first introduced the expression about there being “a fine line between genius and insanity.”

Tsuji also possessed a wide range of knowledge beyond languages. It was him who encouraged Ito Noe to go over to Hiratsuka Raicho’s Bluestocking Society, and some of the early manuscripts written under Noe’s name were in fact written by Tsuji.

Ironically, it was Noe’s involvement with Bluestocking Society which would consequently lead her to leaving Tsuji—she became so absorbed in the movement that she ended up falling in love with anarchist Osugi Sakae. Meanwhile, Tsuji himself was hardly working at all.

Oh, and he also had an affair with a relative of Noe’s. Perhaps there was blame on both sides…

It was at the age of 38 when Tsuji’s life went awry. (Well, he was already out of his mind by the time he met Noe, so it might be more appropriate to say that that’s when his life went completely awry.) In the turmoil following the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, Noe along with Osugi were killed by the authorities.

That’s what did it. Tsuji had ultimately always been fond of Noe, and the impact of this news caused him to dive headfirst into alcohol. He writes:

If you were to ask me what my hobbies are, I would tell you that it’s reading and drinking. Take those two things from me, and my life would be reduced to zero.

But this incident would cause his alcohol intake to increase even further. Kojima Kiyo, who was living with Tsuji at the time, remembers:

That’s when it started—that is when Tsuji Jun became a full-blown alcoholic.

Until the very end of his life, Tsuji would continue to carry a picture of Noe with him. One can imagine how big of a shock her death must have been for him.

In his main line of business, Tsuji was at his peak in the final years of the Taisho era (1912–1926) to the early years of the Showa era (1926–1989). Right around the time before the earthquake disaster he came to know of Dadaism through his translation work, and he soon began calling himself a Dadaist, henceforth becoming a “thinker” as well. It was also Tsuji who first discovered Hayashi Fumiko and Miyazawa Kenji amidst the literary circles.

“Dadaism” is a word you no longer come across in the present day. But back then, it created a sensation. Even Tanizaki Junichiro acknowledged how well-informed Tsuji and his friend Takebayashi Musoan were concerning the subject.

With that said, one’s understanding of any given subject—no matter how deep it may be—has no correlation to their behavior.

Author Yamamoto Natsuhiko, who had known the pair since childhood, declared that despite their extensive knowledge, Tsuji and Takebayashi were both “no-good people.” Meanwhile, fellow author Yoshiyuki Junnosuke stated that there was nothing noteworthy about either of these men or about Dadaism for that matter. (Yoshiyuki’s father, by the way, was Yoshiyuki Eisuke, a Dadaist who had contact with Tsuji. Eisuke’s wife, Yoshiyuki Aguri, became the protagonist of the 1997 NHK morning TV drama Aguri, and in this adaptation the character based on Tsuji Jun is portrayed as a mere “master extortionist.” How terrible.)

While Dadaist writings from this era can be rather nonsensical in certain respects, Tsuji’s writing was very plain and it attracted many fans. Tsuji wrote, “If the bourgeoisie are demons, then the proletariat are brats.” He also said, “I am neither a socialist nor an anarchist.”

The reason I’m not an anarchist or a Marxist or anything like that is because, unlike those people, I cannot hold myself to any admirable “ideal.” Or, rather than me being unable to hold such ideals, it’s really that I’m unable to attain them in the first place.

If I did possess any one ideal, it would be the “unideal.”

Tsuji Jun was a unique individual; someone who opposed all authority and valued the free spirit over everything else.

As Tsuji became a daily drinker, he began to lead an increasingly “unique” sort of lifestyle indeed.

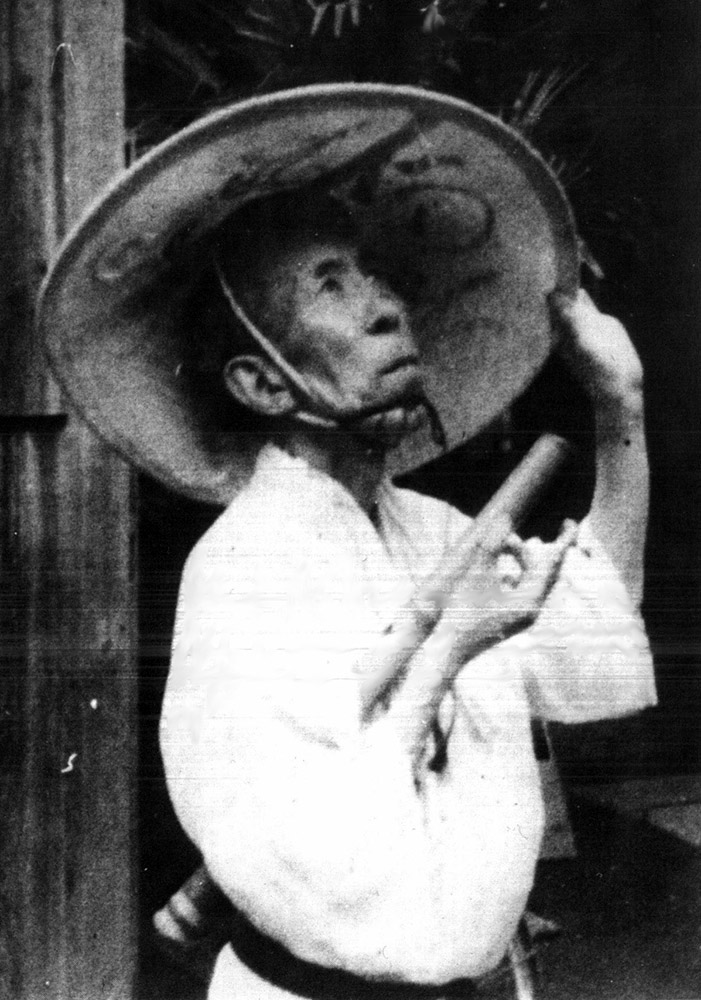

In the Showa years, he was often causing a stir in the newspapers due to his “genius’ eccentricities.” Many times when they found a homeless-looking, filthy man lying on the street and took him into custody, it would turn out to be none other than Tsuji Jun.

For instance, one time in 1937 when he was taken into custody in Kyoto, he was dressed bizarrely in a torn business suit, straw hat, and women’s geta sandals, violently swinging around a wooden cane. Once the police had restrained him, he introduced himself as “Tsuji Jun, the writer,” listed off the names of his works, and—using English, German, and French—began quoting them names of distinguished authors from the East and West. He hadn’t the slightest clue, however, as to where he was or how he had gotten there.

In March 1932, he suddenly ran upstairs in the middle of the night, started strangling the woman he was living with, and screamed out that he had become the mythological monster tengu before jumping out the second floor window.

This was the so-called “Tengu Incident.”

While it didn’t earn him quite as much publicity as popular Heisei era actor Kubozuka Yosuke who jumped from his ninth-floor apartment, Tsuji’s stunt really was something rather sensational at the time. Yomiuri Shimbun reported about it as “TSUJI JUN BECOMES TENGU!” Each time the papers said how Tsuji Jun had gone crazy, the readers were never buying it. “Yeah, right. Again?” But this time around, they were saying it was for real—he really had gone crazy.

On one occasion, before he became a tengu, Tsuji dropped by at a friend’s house on his way back from a bathhouse. He poured his friend something from his gourd, telling him that it was “the tengu’s alcohol.” While his friend had no idea what he was on about, he tried some only to then discover that it wasn’t even booze at all—it was just water.

As the sound of military boots on the ground grew louder, publishers could no longer afford to put out books by writers like Tsuji, and even magazines which had previously allotted him space on their pages had suddenly disappeared. Even while opposing authority, it was not an easy nation to live under.

Strapped for money and with no place to stay, Tsuji liked to fall back on the “telegram, telegram!” scheme. With limited methods of communication available back in those days, what people would use in times of emergency was the telegram. Thus, if you went banging on someone’s door while shouting “telegram, telegram!,” most households would open the door to see what it was.

In his book, editor Nohara Kazuo writes how fellow writer Dazai Osamu would similarly use the “telegram, telegram!” technique when visiting friends’ houses at night. But even though the two of them did essentially the same thing, there’s a big difference when it’s done by Dazai, who did it as a joke and people actually recognized that it was a joke, and when it’s done by Tsuji, who did not intend it as a joke and the people did not see it as one.

To make matters worse, he would try to force himself on any women that he found in the homes he infiltrated, even when it was his friends’ family members—occasionally, even when it was their elderly mother. The guy was an absolute nuisance. And yet, surprisingly, they would continue letting him stay over simply because, “Well, you know how Mr. Tsuji is—he can’t help himself.”

Whether this was human virtue on their part or merely a sign of the times, I do not know.

There are various theories as to why his eccentric behavior made itself manifest. Some have pointed out that he had a manic-depressive temperament to begin with, while others theorize that it was syphilis that made him go crazy. Even when he was with a woman he was dating, he would apparently try to lay with other women before her very eyes. Considering how loose Tsuji was with his nether parts, it would have been more strange if he didn’t have syphilis.

There’s also the theory that it was drugs.

Tsuji knew French literature scholar and translator Hirano Imao, and they were said to have been good buddies. Not translator buddies, mind you, but drug buddies. Hirano was a proper drug addict, being admitted to and escaping from a mental hospital, repeatedly committing acts of shoplifting while he was on the run, breaking into his brother-in-law’s pharmacy to steal cocaine… While of a different orientation from Tsuji, this was another rather unhinged individual. (By the way, Hirano is the father of culinary expert Hirano Remi.)

Another persistent theory is that Tsuji’s eccentric behavior was feigned, with people suggesting that he was simply pretending to be a madman in order to deceive the watchful eye of the authorities.

Under the wartime regime even speech was controlled, and what with him being a Dadaist, Tsuji was initially a marked as a “dangerous person” by the authorities. But as he ran around shouting “Glory to the Emperor!” while looking like an outright vagrant, they eventually figured the man was just out of his mind, and they left him be. It is not out of the question that Tsuji—upon learning of the deaths of individuals like Kotoku Shusui and Noe—simply pretended to be crazy, thinking to himself, “These people killed them. But I’ll be damned if I’m going to let them get me.”

Ultimately, the reasons are unclear.

But while there may have been more than one cause behind his eccentric behavior, the current prevailing theory is that alcohol, for sure, was a major factor. The harmful effects of alcohol were not yet deeply understood in Japan at the time, therefore leading to the emergence of these various theories.

In the final years of his life, even while short of money, he still managed to get by thanks to his supporters—the “Tsujimaniacs”—who would offer him a place to sleep.

By this point, however, his writing had virtually come a halt. Partly presumed dead during the war, his name was removed from the directory of living writers, showing you the extent to which he no longer had a presence.

Freeloading at other people’s homes and various temporary residences, people still had food to spare at the beginning of the war. But as the war was drawing to a close, so too was the food situation growing dire everywhere. Even so, Tsuji would not accept any food rations. (He would accept food from his friends, though, so one kind of feels like telling him to just take the damn rations. But that’s Tsuji for you.)

His son, Tsuji Makoto, looks back on his father as follows.

Generally speaking, people would describe his final years as “miserable.”

But were they really? As far as I know, he was the only Japanese person who was never, ever defeated on a human level.

(“Tsuji Makoto Selection 2: Geijutsu to Hito”)

In the end, Tsuji died of starvation at an acquaintance’s house in 1944.

To be true to oneself, or to just go with the flow—even in the present day, it’s a choice every company employee has to make.

Tsuji took the “staying true to himself” thing so far that he became an alcohol abuser and ultimately died, losing it all. And yet, it’s also true that it’s only the people who stay true to themselves who are capable of creating new eras in culture. Sure, Tsuji may have died of starvation. But then hindsight is always 20/20.

So if that booze-loving boss of yours suddenly begins practicing his bat-swinging skills at the office, it’s not like he’s going to listen to you even if you tell him he ought to start moderating his drinking. After all, his chances of becoming a professional baseball player at the age of 50 aren’t zero.

Just like how people used to say, “Well, you know how Mr. Tsuji is—he can’t help himself,” you ought to extend the same courtesy to your section chief and just warmly watch over him. Perhaps it’s precisely this sort of kindness that is lacking in our modern society.