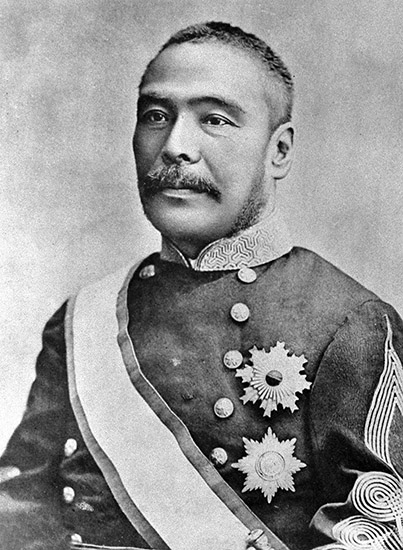

Kuroda Kiyotaka

If your boss accidentally fires a cannon

Politician | 9 November 1840 – 23 August 1900

People who become annoying when they are drunk. Surely you, the reader, know one or two individuals who would fit that description.

There’s drunks like me: guys that are usually quiet who suddenly get all jovial, guzzling down booze by themselves like it was water until suddenly you notice they’ve passed out.

But then you also have the guys who can get surprisingly belligerent. While you might yourself be feeling nice and woozy, you can never quite totally relax when you’re drinking with these individuals. You never know when that switch inside of them is going to flip.

They’re the sort of people who are going to pester other customers and waiters, sometimes with verbal abuse. More than just once or twice, I have personally had to apologize on behalf of these people. One drunk apologizing for the misbehavior of another drunk to a third party who is in all likelihood also drunk themself—it’s the Japanese izakaya hellscape.

It’s one thing when it’s just abusive language. But when hands and feet also become part of the equation, that’s when it starts to get really bothersome.

To be fair, these days there are fewer people who get physical like that. But if you take a look at historical figures of the past, you will quickly discover many individuals who would involve not only their hands and feet, but even swords. Even in this book we’ve discussed actor Mifune Toshiro who, when drunk, would bring a real sword out to his garden and swing it around for practice, making his family so distraught they had to plead Kurosawa Akira for help.

But while there have been other eminent figures who have similarly been known to brandish swords, Kuroda Kiyotaka is surely the only one to have been suspected of using said sword to slay his own wife.

For most of you reading this, you probably remember Kuroda Kiyotaka only from your junior high school history textbooks which told you he was Prime Minister during the promulgation of the Meiji Constitution.

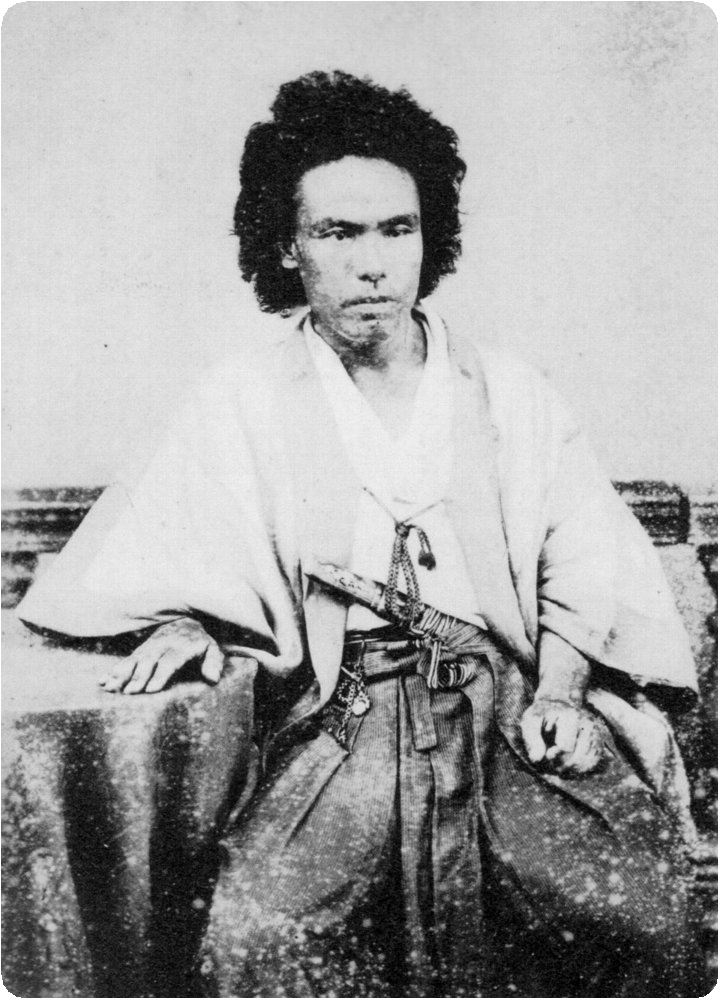

Born into one of the lowest-ranking samurai families in the Satsuma Domain, he took part in the Boshin War, fighting in the battles of Toba–Fushimi and Goryokaku. Consecutively holding the posts of Lieutenant General, Councilor, and Hokkaido Development Director, he then served in the Satsuma Rebellion, successfully driving back the forces in Satsuma.

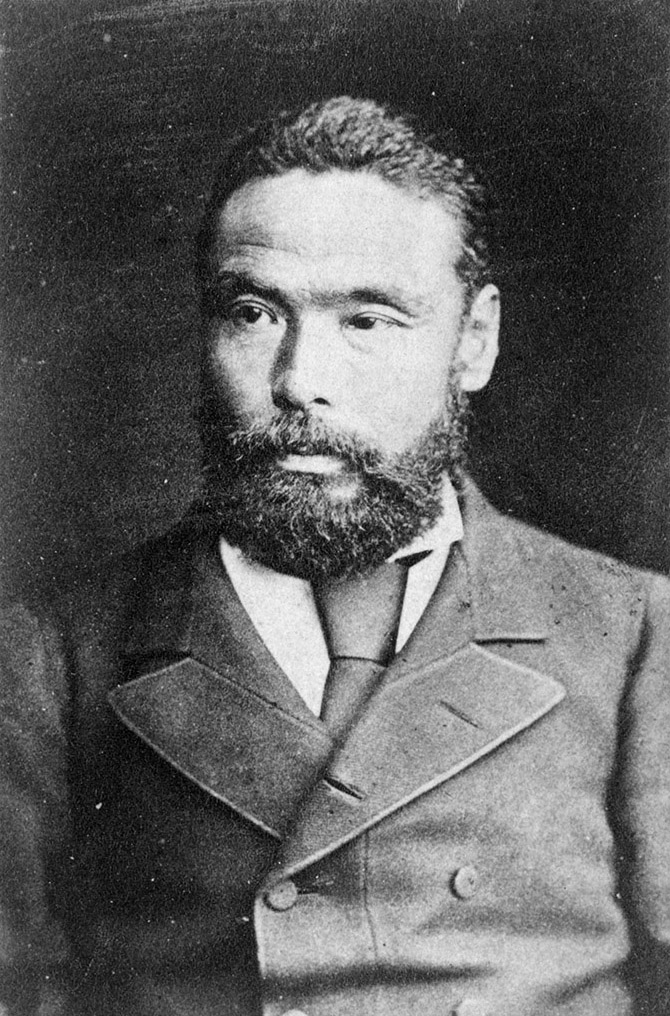

With the deaths of Saigo Takamori and Okubo Toshimichi, he unexpectedly became the leader of the Satsuma Domain. Then, succeeding Ito Hirobumi, he was inaugurated as Japan’s second Prime Minister in 1888.

The above serves as a brief curriculum vitae of the man. However, it is not for the reason of celebrating Kuroda Kiyotaka’s achievements that he is featured in this book. Rather, it is because as mentioned earlier, he was such a terrible drunk that it has become an established fact that he slaughtered his own wife.

Kuroda had a penchant for swords, and he often liked to pull one out when he was drinking, giving him a reputation for being somewhat on the crazy side.

But then again, that’s just the sort of time it was back then. Not all that long ago, it was commonplace for people to be going at it with swords against total strangers. You might suddenly slash at someone or get slashed yourself, and not only on the battlefield but even just on the street. Thus, someone like Kuroda taking his sword out was really no big deal at all.

But as for the central issue of the murder of his wife, Kuroda himself of course never stated that it was he who did it, nor is there any evidence to prove it. The scary thing is how, despite this, people have always said that he had indeed killed his wife like it was a basic fact. “A guy like that? Yeah, he wouldn’t hesitate.”

The story goes that one night in March 1878 as Kuroda returned home in a drunken stupor, he took offense to his wife, Sei, taking too long to come and greet him, and thus he proceeded to slay her with his sword. Sei, the daughter of a former shogunate retainer, was 23 years old.

Kuroda, 38 at the time, was one of the top-ranking councilors of the new government. When this murder was exposed in the Marumaru Chinbun newspaper, it caused great turmoil in society. But just when his resignation seemed inevitable, Okubo Toshimichi—the most powerful man at the time, and fellow Satsuma native—emerged to cover things up.

His trusted confidant, Police Superintendent-General Kawaji Toshiyoshi, while acting on orders from Okubo, personally went over to exhume Mrs. Kuroda’s grave so that an autopsy could be performed. Once the body had been dug up, Kawaji gave it a cursory glance, reported that there were “no signs of murder,” and the case was closed. (This is believed to have been the origin of the traditional Japanese art of sontaku. Maybe.)

Even Shiba Ryotaro writes in Tobu ga Gotoku how “Kuroda, after returning home in a drunken haze, apparently slashed his wife dead over some trivial matter.” He even includes the bit about how Kawaji, acting on Okubo’s orders, dug up the body and arbitrarily decided there was no sign of foul play.

When you even have a national bestselling author giving this description of the events, it is now for all intents and purposes the commonly accepted theory that Kuroda did, in fact, kill his wife.

Shiba describes Kuroda as “surely atypical, for after he had consumed a certain amount of alcohol there would always be a complete change in his character.” Describing Kuroda’s behavior towards his own higher-ups like Sanjo Sanetomi and co-workers like Ito Hirobumi and Inoue Kaoru, he says Kuroda would “verbally disparage them and threaten them with his pistol.”

The way he makes it sound like Kuroda would consume anything that contained alcohol, and was then always eager to reach for a sword, pistol, or anything in-between… It certainly does paint a picture of a proper drunken maniac.

With that said, one thing that kind of bothers me about not just Shiba’s description but about many of the accounts discussing Kuroda’s wife-slaying is how they make it out to seem like all bad drunks are somehow liable to murdering their wives.

In fact, when you do even just a little bit of research into this particular matter, you’ll immediately notice how different sources give different reasons behind the murder (with some saying Kuroda became enraged because his wife was late in welcoming him home, some saying it was because she got angry at him because he had been entertained by geisha, etc), differing accounts as to Okubo’s involvement in “putting out the fire,” and so on and so forth.

Thus, speaking as a fellow dipsomaniac separated from Kuroda only by space and time, I have to say I feel kind of sorry for him. Someone who was once Prime Minister, threatening his friends with a pistol and slaughtering his wife—that’s a level of shame that is going to last for generations to come.

While just now I used the expression “for generations to come” sort of in the heat of the moment—and while I digress—the astonishing thing is that this incident literally did become a source of shame lasting for generations.

In Asahi Shimbun‘s 2005/1/5 Morning Edition, they reported about the experiences of Kuroda Kiyotaka’s great-grandson, Kuroda Kiyoaki. “He said he’s had it happen where he’ll be drinking and someone will start ridiculing him by saying, ‘Ooh, scary! I don’t wanna sit next to Kuro-chan—I might get slashed!'”

Kiyoaki, 74 at the time, was enraged by this, saying it was “too much.” And it is too much. “Hey, your great-grandpa killed his wife, didn’t he?! Fess up! Ha ha!” It’s like adolescent bullying. The real scary thing here is people mocking someone for something that happened over a hundred years ago.

Finding myself feeling sorry not just for Kiyotaka but also for Kiyoaki, I suddenly felt driven and began researching for material. To my surprise, I soon came across a rather shocking book.

That book is Iguro Yataro’s Pursuit: The Death of Mrs. Kuroda Kiyotaka. (Can’t get much more to the point than that!) What’s amazing about the book is its premise, as implied by the title, that Kuroda was undeniably the killer. No question about it. Kuroda? More like Killerda.

Jokes aside, according to the book, when the newspapers exposed Kuroda’s alleged murder of his wife, it was feared that it might lead to an anti-establishment movement. The government thus had to make a move in regards to this Kuroda problem.

Panicked, the government held an extraordinary meeting of the Cabinet. The book details how someone behind the curtain, under orders from Iwakura Tomomi, eavesdropped on the cabinet meeting. This individual then made their confession about the meeting in 1912, thirty years after it happened. (I just kind of wrote it like it’s no big deal, but there was literally a man behind the curtain listening in. I feel like more than Kiyotaka, the truly frightening individual here is this Iwakura character making someone eavesdrop on a meeting of the Cabinet.)

As for his confession, what was immediately surprising—although the truth was not yet clear at the time of their discussion—was that it appeared likely Kuroda had not cut his wife with a sword, but rather kicked her to death.

“Cut to death” vs. “kicked to death.” It’s only a one-word difference, but it still gives quite a different impression. I mean, it’s still murder just the same. But you know.

Complicating matters at the meeting was a political issue between the domains of Satsuma and Choshu. As this scandal was caused by Kuroda (a Satsuma native), it was then Ito Hirobumi (a Choshu native) who saw an opportunity and went, “Dig it up! Excavate the grave and do a proper investigation!”

Try and picture the scene. A man at a cabinet meeting—where they could potentially be deciding the future of an entire country—screaming in indignation to dig up a corpse. These Meiji era politicians were all so… dark.

While Ito was furious, one of the other attendees, Justice Minister Oki Takato, told Ito that they wouldn’t be able to do something like that when there was no evidence. Indeed, had the wife been killed with a sword, it would be plain to see. But had she instead been kicked to death, ascertaining that fact would require an autopsy, making it all the more difficult.

The argument went on and on, until finally someone asked what Okubo, the supreme authority, made of all this. Okubo said, “If you have trust in me, then I wish for you to also have trust in Kuroda.” Being told this, even Ito fell silent. Everyone came to an agreement, and the meeting was adjourned.

In short, based on what was said at the cabinet meeting, it seems doubtful that Okubo actually gave out instructions to have the grave dug up. Furthermore, as per the perception of the person who did the eavesdropping, there was no rise in anti-establishment sentiment following the cabinet meeting.

Of course, based on this information alone, we still cannot say for sure that Kuroda didn’t kill his wife, or that Okubo didn’t order the exhumation of her remains. The question is: despite the details of the case being so unclear, why have these theories about Kuroda slaughtering his wife and her grave being dug up remained so widely accepted to this very day?

Sorry to ambush you with a question like that. But the answer is simple. While thus far I have been sort of defending the guy, I’m afraid I now have to totally flip the tables on him.

It’s really no wonder at all that Kuroda was suspected of murdering his wife.

Two years before the alleged murder. Summer of 1876. Kuroda was responsible for something called the “Director Kuroda Cannon Incident.”

Kuroda, who was the Hokkaido Development Director, suddenly fired a cannon aboard the ship he was on, aiming at some reef on the open sea. He misfired, and the shell landed on the hut of fisherman Saito Seinosuke. With fragments flying everywhere, the man’s daughter, who was in the central room of the hut, was seriously injured and died.

While the reason for this bombardment is a mystery, there is a theory that the drunken Kuroda was annoyed because of a prior argument with another person onboard, Dr. William S. Clark—famous for his slogan “boys, be ambitious!“—which prompted him to order the shelling.

While there are numerous theories out there, one thing they all have in common is the understanding that Kuroda was drunk when it happened. The only remaining point of contention is: exactly how drunk does one have to be to order a cannon bombardment? No matter how favorable of a view we might try to adopt, this really was just drunken violence, pure and simple.

Kuroda, who held judicial authority at the time, tried to settle matters by imposing a fine of 100 yen on the ship’s captain, as well as collecting 40 yen from the ship’s supervisor to give to Seinosuke for burial fees. Naturally, Seinosuke was furious, and this matter became a major controversy.

To reiterate: what happened here is that Kuroda got drunk and accidentally shot a private individual. Kuroda got drunk and accidentally shot a private individual. It’s such an astounding thing, I had to say it twice.

It’s not the same as missing the urinal in the pub toilet and accidentally pissing your pants. It’s not the same as getting drunk and mistakenly walking into the wrong room in karaoke, startling a group of young college girls into thinking you’re some creep. It’s not the same as drinking yourself unconscious at a hostess bar, accidentally falling onto the table next to yours and getting into a fistfight about it.

No. This man got drunk and accidentally shot a private individual.

Okay, this story’s gone so off the rails it’s like a Shiba Ryotaro novel.

In any case, Kuroda Kiyotaka’s alleged murder of his wife speaks to the true tragedy of drunkenness.

Ultimately, once you commit even a single crime while drunk, people no longer deem it strange at all even if subsequently you were to slash or kick someone to death. I mean, to be fair, Kuroda’s crime was shooting someone to death. But let’s leave that aside for now—it’s sort of difficult to try and justify it in any way. (The real weird thing is how, when they were running out of capable personnel after the deaths of Saigo and Okubo, they thought Kuroda of all people was their best bet for Prime Minister.)

There is something we can learn from Kuroda Kiyotaka.

If you’re making one drunken mistake after the other at the bar, it is going to lead to irreparable consequences. If a colleague of yours was to claim they saw you drunkenly walking into a dating club one night, and if later you were to be suspected of workplace power harassment or sexual harassment, people are going to be talking about you behind your back. “Oh, that guy? Yeah, wouldn’t surprise me at all if he did do it.”

At the same time, it also doesn’t have to mean your career path has been cut off forever. No matter how much they might call you a violent drunk or an incompetent ass, Kuroda Kiyotaka is a faint beacon of hope for all salarymen out there. He allows one to think, “They can talk behind my back all they like. I can still make it and become Section Chief—no, Executive, even!”

Although, of course, that could well just all be wishful thinking.