Fujisawa Shuko

If you have important work to do but you become an alcoholic

Go player | 14 June 1925 – 8 May 2009

“What’s more important, me or alcohol?!”

If there was a woman asking you that in tears, what would you say? “No one’s ever asked me that and no one ever will. It’d be pointless for me to even contemplate.” Now, now. You mustn’t be so uncouth. After all, it’s good to have a shelter for every storm.

I read this in some magazine over a decade ago, but apparently if one was to answer the question above with “alcohol,” that would mean they were on the verge of becoming someone with an alcohol dependency problem (hereafter referred to as “alcoholic”).

In my younger days I would have said, “I mean, okay, but be that as it may… Still it’s gotta be alcohol for me.” For better or worse, alcohol will never betray you. Although, of course, if you enter into a close relationship with alcohol, it suddenly becomes more dangerous than any woman out there.

Although the word “alcoholic” may have a rather distant feel to it if you’re the average respectable salaryman, there are roughly one million alcoholics in Japan. Furthermore, their “reserve army” is said to number at nine million. And yet, even many of the people who just love to drink would be quick to exclaim, “Alcoholism, hah. That’s got nothing to do with me!”

In fact, it’s got quite a lot to do with you.

There are folks who’ll get bad figures at their health check-ups because they like to get wasted on a daily basis, so they cut back a little—just until their numbers improve—and then it’s right back to chugging again. These people don’t know it, but they are all members of that reserve army.

Drinkers like to imagine there being a river as wide as the Yangtze between themselves and someone who is an alcoholic. In reality, what flows between them is at best one of those little artificial streams you see at all the city parks. They could easily jump over it any second.

You need to be aware that you currently stand in a spot where you could at any moment cross over to the side of the alcoholic who might cause the breakup of your family or get you fired from your job. To begin with, even the fact that you’re reading this book is already a pretty big warning sign in itself.

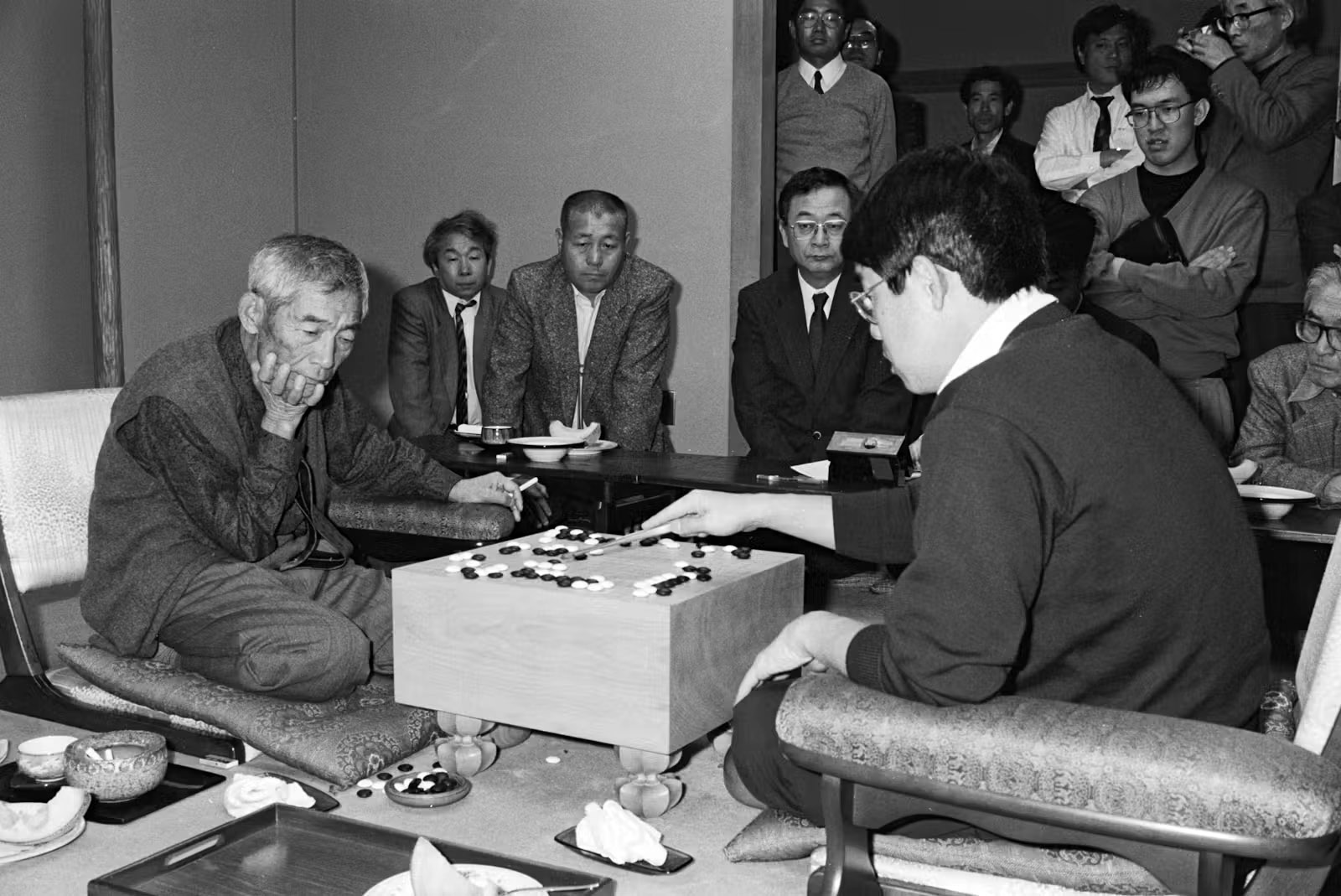

Now, when it comes to men who, despite being alkies, would continue producing results at work, there is probably no one who compares to professional go player Fujisawa Shuko.

Known as the greatest go player of the Showa era (1926–1989), winning over 23 titles including those of Kisei and Meijin, it was his personal life rather than his day job that attracted him attention. Booze, gambling, and debt—the man had all three bases covered.

But another constant presence in his life was violence and trouble with women.

He had seven children between three different women. He was rarely home. One time, as he was thinking of going back for the first time in three years, he realized he’d forgotten where his home actually was. He eventually had to phone his family from the nearest train station so they could come and pick him up. This guy—someone trying earnestly to just live his life—was infinitely funnier than some comedian telling stories with distorted facts.

Some alcoholics are mean drunks—they sometimes get verbally or physically abusive. The sad thing about Fujisawa is that nearly every story involving him and alcohol contains some form of abusive language, so it is difficult to determine exactly how much of it was due to alcoholism and how much of it wasn’t.

One well-known example of this is how, no matter who he was drinking with, he greatly enjoyed shouting out in rapid succession the popular slang term for female genitalia. It seems he did this in part just to enjoy the frowns on nearby women’s faces, but at the end of the day, no one really paid much attention. Ultimately, he just liked yelling out obscene words.

Apparently, he really did not care as to where he was or who he was with when he did it. One time he yelled it out in front of 2,000 spectators, while on another occasion he was in China where he was granted an audience with then-Supreme Leader Deng Xiaoping, only to drunkenly pester him by asking, “How do you say ‘pussy’ in Chinese?!”

In his book Dying a Dog’s Death, he explains how his usage of the word did not have any special meaning, but that he was “just using it as a greeting, similar to how I’ll shout out, ‘idiot!’” Of course, this serves as no actual explanation whatsoever—he just comes across as a bona fide pervert. But then it would be foolish to expect common sense from a genius.

When not even Supreme Leader Deng Xiaoping could faze this man, it is only obvious then that he would be constantly getting into disagreements with ordinary people, too.

One time he picked a fight with a professional fighter he happened to come across on the street, whereas another time there was a phone call made to his home with the party on the other side saying, “That man is not human. Under no circumstances do I wish to have anything to do with him ever again.” Sort of makes one curious as to exactly what level of violence would warrant a phone call like that.

This man would lash out violently regardless of time, place, or who it was against.

Naturally, the police station thus became almost like his go-to guest house. But eventually, even the police started to feel silly because of how often they were having to lock him up. One time, when a newbie officer took the drunken Fujisawa down to the station, they actually got angry with the rookie, going, “Just who do you think you have there?!”

Understandably, when a human weapon like Fujisawa makes the rare trip back home, you can be sure that the violence is going to be out of control. Especially if you’ve happened to lock the front door—that’s just a disaster waiting to happen.

If you read The Gambler’s Wife, a book by Fujisawa’s wife Moto, you’ll find yourself at a loss for words.

“Son of a bitch!”

Shouting in anger, he first destroyed the entranceway door. […] Then, he entered the house, still wearing his shoes, and destroyed the bathroom door. Next, he destroyed the kitchen entrance door. They were both sliding doors fitted with four frosted glass panes, and he kicked them down, cracking the glass all over. […]

Other times he would break the glass with his fists, causing his hands to be covered in blood. […] He’d go on a rampage until he was satisfied, throwing and breaking all sorts of things before finally taking off his shoes, tossing them somewhere, and falling asleep while snoring loudly.

Sometimes, after his rampage, he would just head out again. I believe he was going to some other woman’s place.

This was scorched-earth levels of drunken violence. You could have a B-29 fighter plane bombing a designated area and it would still not result in this level of devastation.

Apparently, Fujisawa’s riotous nature was well-known within the neighborhood. Whenever he was seen coming home, mothers in the vicinity would quickly call for their children to run back indoors and take refuge. If a day or two happened to pass without a violent incident, the neighbors would be chatting how “he’s been awfully quiet as of late.” (There’s a good chance he simply hadn’t been at home to begin with.)

Incidentally, writer Kaiko Ken also lived in the same neighborhood. In his essays, he wrote about “some man who yells obscenities night after night after night.” He apparently wasn’t aware how that man had, in fact, been Fujisawa all along.

So that is the sort of drunkard Fujisawa was. The one thing he was serious about was go. As he got into his forties, however, the drinks he’d had the previous night would still remain in his system the following day, often causing him to run out of steam near the end of his games.

Usually, when professional go and shogi players turn into problem drinkers, their careers tend to go downhill. Serizawa Hirobumi, a 9-dan shogi professional once considered a future Meijin class candidate, was someone who also turned to the drink. Boasting how he was “better at drinking than I am at shogi!,” he ended up losing his battle against alcohol, uncrowned, at the age of 51.

But Fujisawa was different—he saw how this wasn’t going to work for him. He thus made the switch to a style where he would cut himself off from alcohol in the days preceding a game, in exchange allowing himself to drink to his heart’s content as soon as the match was over. As a consequence, his results only started to improve from this point onward.

“If you have to go so far as to cutting yourself off from alcohol, how about just drinking less to begin with?” One would think so, yes. But of course, for Fujisawa, abstaining from drink was easier said than done.

His alcoholism was progressing day by day, and soon he was getting withdrawal symptoms if he went two hours without a drink. He would have hallucinations, and feel as if he had insects crawling all over his body. Even then, the fact that he was able to voluntarily stop himself from drinking shows just how passionate he was about go.

With that said, the instant the match was over, it would be straight back to drinking from morning while not eating a thing. It was gradually becoming more difficult for him to stop drinking on his own. If he was at home, he would soon start looking for cooking sake, phoning liquor stores, and turning over all the furniture in search of something to drink.

In his later years, Fujisawa won the Kisei championship on six consecutive years (second time in the history of the game). Around this time, it is said that he would confine himself in a hotel room sometimes several months prior to his matches, and abstain from alcohol. However, even then he was by no means in perfect shape, neither in body nor mind. Having lost around 20kg (45lbs), he would show up at the match looking like a completely different person, startling his opponent. He must’ve looked so eerie, go was the last thing on his opponents’ minds.

But really, I can’t be the only one who thinks that if you are capable of abstaining from alcohol, you could just… not drink so much to begin with.

But then Fujisawa seems to have been fully prepared for the eventuality of retorts like mine. In Dying a Dog’s Death, he explains: “It’s only because of alcohol that I could play that level of go.” (Really now? It kind of feels like doubling down this way was his only play here…)

While it is true that Fujisawa may be an extreme example, if there is something you feel you absolutely must grapple with—even if your body is saying it wants alcohol and it feels like you’re going to die—surely one can quit drinking. For this man, when he was playing go, it was always a matter of life or death. In every game that he played, he felt like either he or his opponent was going to get their head chopped off.

Although, ironically, even before the match began, he would have already tasted death in his struggle to give up alcohol.

The key is to have that one thing that is an “absolute” for you. Whether it’s your work, partner, family, friends—what that thing might be in your case is not for me to know. This is something that applies even if you’re not quite as bad as a “genuine alcoholic,” but you just want to cut back and do something about the amount you are drinking.

But despite me trying to sound like some perfect saint in what I just wrote above, when Fujisawa pushed himself to the limit before those championship tournaments of his, it may not have been merely because of his passion for the game. It may also have had something to do with his financial difficulties.

Before the establishment of the Kisei tournament—which offers the highest prize money in the go world—Fujisawa was nearly 300 million yen (USD$2M) in debt. It got so bad that he even lost his house when it was auctioned off, but he subsequently managed to repay nearly all of his debt during his streak of six consecutive championships. Looking back, he says how during the streak he was also giving many speeches, making him a good additional chunk of money.

You might be thinking, “Wait, what? So ultimately it was just all about money? That’s the punchline?” Ultimately, it sure seems like that’s the punchline. But then the fact that he was able to win so big at the last moment, even when he was up to his neck in debt, I suppose he could only do that because of his passion for go.

Fujisawa would continue to drink until the final years of his life, even while staring hell in the face. One man who had contact with him in his later years looked back on that time, saying:

He was always wasted. He’d ask for an oolong highball, but you could just hand him a regular oolong tea and he wouldn’t even notice because he was so drunk.

As one would expect, this lifestyle must have taken a toll on him as he developed a stomach ulcer and started vomiting blood. He was found to have stomach cancer, but even then he continued to drink. In the end, suffering from lymphoma, his body would no longer accept alcohol, and he died of pneumonia in 2009 at the age of 83.

Considering how the average life expectancy of an alcoholic is 52 years (as per a study by the All Japan Alcohol Abstinence Union), it is probably fair to say that in addition to his skill in go, this man’s physical strength was similarly well beyond the norm.