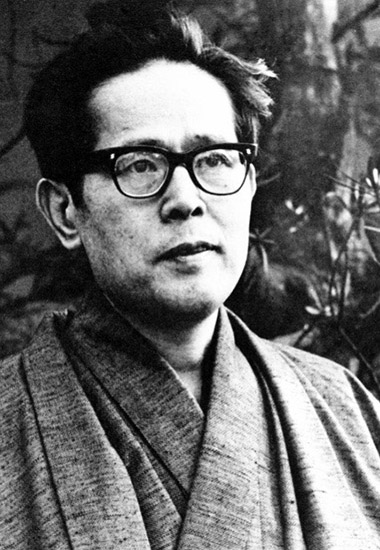

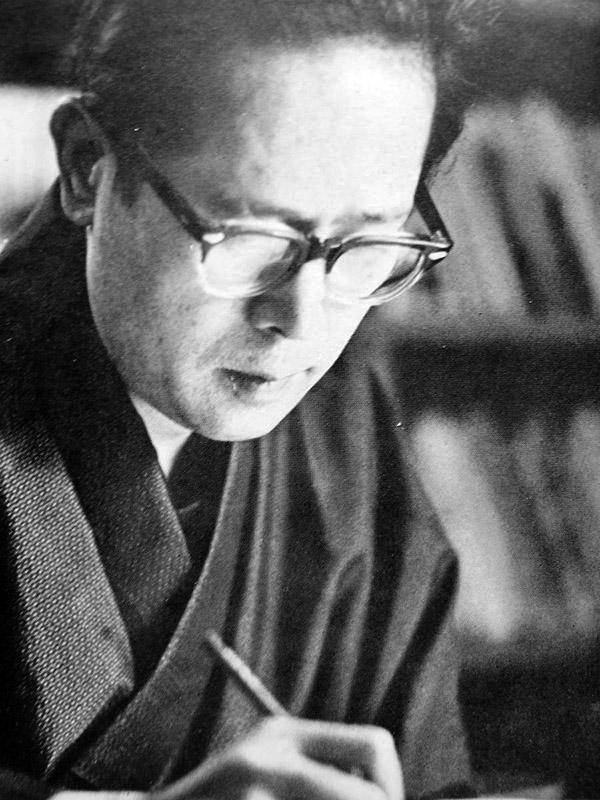

Umezaki Haruo

If you start drinking methanol

Author | 15 February 1915 – 19 July 1965

There was a time when my body would not accept sake. Whenever I drank it, I would always feel unwell the next morning. I was a big beer drinker at the time, so I figured that perhaps sake just wasn’t for me.

But as I became a working adult and got more opportunities to drink the stuff at fancier places, I realized something: what I had been drinking back then had not been the real deal. See, what with me being so broke, I would have to go out drinking in more dubious places, and I’m guessing what I had been drinking there had actually been cheap, synthetic sake.

Synthetic sake is, in a narrow sense of the word, different from actual sake. It’s an alcoholic beverage which includes amino acids and other food additives, but of course I had no clue about any of this back then. Some of you might now be scolding me. “Who cares what it is as long as it gets you drunk. Don’t be such a damn snob.”

It’s true that there are people out there who do not care what it is they’re drinking so long as it contains alcohol. Some people can drink anything and everything and still be completely fine. Be that as it may, there are plenty of examples in history of people who—because of their single-minded desire to get drunk—chose the wrong kind of alcohol to drink, and it nearly cost them their lives.

Umezaki Haruo was a writer born in 1915. He won the 32nd Naoki Prize for Occurrences of an Old Dilapidated House in 1954, and he was regarded as one of the first post-war writers along with people like Noma Hiroshi and Shiina Rinzo. Although I suppose unless you were a big literature buff, you’d be thinking, “I don’t know any of these people.”

While Umezaki’s presence is quickly becoming smaller and smaller with each passing year, as we now find ourselves in the 21st century, our way of life having grown weak and weary, now is actually the perfect time for us to re-examine this man. Today, as Japan has become frighteningly powerless while it advocates for a work-style reform, I personally believe that this man is one of those people to whom we should all be paying renewed attention.

Umezaki enrolled at Tokyo Imperial University (now: University of Tokyo), but he did not attend his lectures there and he failed all his job exams. He managed to slip into a part-time government office job, but even after he did, his desire to work remained elusive. During the war he was called up for military service, and it was after his demobilization that he became a writer. Even then, his lifestyle was still no different.

One thing that was absolutely inseparable from Umezaki’s lazy approach to life and his writing style was alcohol.

In Illusions, a masterpiece from his later years, he uses the expression, “The white walls are covered with ants.” This could be taken as just a literary expression, but some people see it as describing the visual hallucinations of small critters—a symptom characteristic of alcoholics.

Struggling with alcohol until the end of his life, he described alcohol for him as being “purely something to get drunk with.” Sure, he could tell whether something was sweet or salty, but he was not at all particular about the taste. He drank simply to get drunk.

No matter how you look at it, what we have here is a full-blown alcoholic.

It was during the war that Umezaki first began showing his talents as a swiller.

Helped in part by the cramped conditions of the war, if you read his diaries from 1943, they will tell you how he was getting drunk five nights a week. And when I say “drunk,” I mean totally stewed. Commodities at the time were scarce—shops had allocations for alcohol which was then rationed out to individuals. Considering all this, Umezaki was really going after it hard.

But as he was busy living the life of a full-time drunk, Umezaki was called up to the Navy in 1944. While claiming he was not yet an alcoholic at the time, he recalls how the navy life was so tiring that it made him want to drink. I must say, though, I think there is a good argument to be made that if you feel you need to drink because you’re “tired,” that pretty much makes you an alcoholic.

In any case, when you’re a regular foot soldier in the army, it’s not like you just get to drink good booze as you please. In Cheap Liquor Days, Umezaki reflects on his drinking habits as follows. It’s a bit long, but allow me to quote it just because it’s so crazy.

Near the end of the war, I was hastily made a petty officer. I thus had a bit more leeway, and as per recommendation of other petty officers, I was now drinking fuel alcohol. It was illegal to drink the stuff back then, so I had to do so in secret.

I’d heard rumors of people on other bases going blind from drinking, but at the time it didn’t make sense to me. Basically, I didn’t know there were different types of alcohol—methanol and ethanol. I thought alcohol was all one and the same.

I drank quite a bit of this stuff called Naval Aviation-Use Alcohol, but to this day I do not know whether that was ethanol or methanol. Seeing as I didn’t go blind, I’m guessing it wasn’t methanol.

You’re guessing it wasn’t methanol? What? This guy was someone who’d gone to an imperial university, yet here he was, playing Russian roulette.

It is difficult for us ordinary people to buy any of the above story. But then again, one must remember how ignorance really is a powerful thing. If the person doing the drinking doesn’t think he’s going to go blind, then it isn’t something he’s going to be afraid of.

You would think this manner of drinking could easily result in one’s death. In fact, Umezaki came very close indeed.

One time at a military base in Taniyama, Kagoshima, I drank something I was sure must have been petroleum, judging by the smell.

There was so much discharge coming out of my eyes the next day… That stuff had to have been methanol. It seems that stopping after just the one teacup is how I managed to not lose my eyesight.

One just wants to reprimand the guy. “How about you don’t drink something you think to be petroleum?!” But then the fact that he stopped after the one teacup must mean that he didn’t exactly love the taste either.

Having read this far, you might be questioning whether this man was all right in the head. However, because this was a time that offered very little in the way of amusement or commodities, there were quite a few similarly deranged individuals around back in those days.

Alcohol remained difficult to obtain even after the war ended, and poor-quality alcohol soon began circulating on the market. Two famous examples are kasutori and bakudan.

Also popular back then was doburoku—homemade moonshine—but the problem was that during this era, ordinary people couldn’t just be making it at will. With this new stuff, however, you only had to throw things into a pot, boil it, evaporate it, and voilà—you’d just made yourself some kasutori.

As a side note, back in those days they were also churning out these erotic, grotesque magazines printed on cheap paper, and they were called kasutori magazines. The reason for a type of alcohol and magazine sharing the same name was because they both led to imminent collapse. In other words: drink three cups of kasutori alcohol and you’ll be unconscious; put out three issues of a kasutori magazine and you’ll be out of business.

Now, bakudan, on the other hand—this stuff was dangerous. This was moonshine made by diluting fuel alcohol with water. Some of it would contain methanol, and for a time after the war it was the cause behind many cases of blindness and death.

Takeda Rintaro, a writer who founded the Bungakukai magazine along with people like Kobayashi Hideo and Kawabata Yasunari, is someone who is also thought to have died from drinking methylated alcohol.

Takeda, by the way, had relations with the wife of a friend of his, Niwa Fumio, who was devastated to learn of this betrayal. Niwa has a detailed account about it in his book Hito Ware wo Hijou no Sakka to Yobu. He apparently came across his wife’s diary containing the names of 47 men who she had had relations with. This anecdote might seem like it has nothing to do with alcohol, but his wife was a regular at bars—she was a Ginza club hostess.

“Poor guy,” you might be thinking. But keep in mind that he was a complete nobody at the time, financially dependent on his wife, and thus he simply put up with it and continued the relationship regardless. So perhaps there was blame on both sides. Although, then again, he also did contract a venereal disease from that wife of his, so…

But to get back on topic, while kasutori tasted horrible and had an awful odor to it, it was not accompanied with the risk of death upon consumption as was the case with bakudan. Consequently, kasutori is what all the heavy drinkers liked to drink.

However, that is not to say that it was by any means safe to drink either. One of Umezaki’s friends drank too much of it, went crazy, and suddenly assaulted a random woman on the street. Umezaki writes that he testified at his friend’s trial, saying the cause had been none other than kasutori.

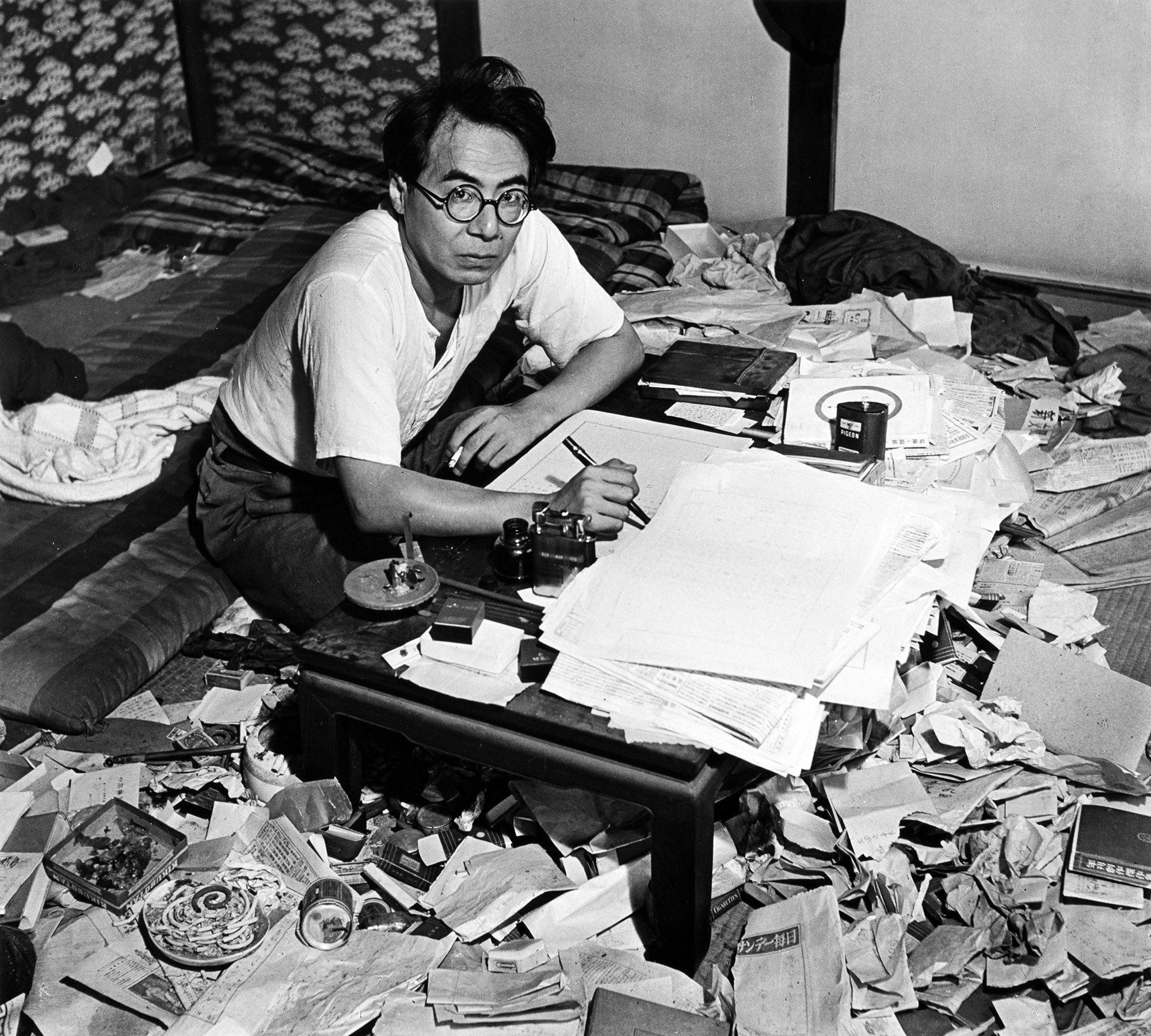

One writer who especially loved kasutori was Sakaguchi Ango.

Ango, known for his hiropon (methamphetamine) addiction, would work for five nights straight while high on the stuff, and once he was done with work, he would get drunk on kasutori so that he might finally get some sleep.

Ango was such a big fan of kasutori that he kept a barrel of it in his alcove, and visitors at his house were free to dilute it with water and drink from it as they pleased. Ango used to work in a room next to the alcove, but since no one had ever witnessed him in the actual process of writing, he asked photographer Hayashi Tadahiko to take pictures of him doing just that.

Many of you surely remember that famous picture of him in his undershirt, manuscript paper spread out on the desk, and him looking straight up at the camera.

Dazai Osamu, on the other hand—although a big time drinker himself—always avoided kasutori. How very typical of the guy. But while he was cautious about his booze, when you consider how he died, one kind of gets the feeling there were a couple of other things that should’ve gotten priority on his list of things to worry about before low-quality hooch.

When Umezaki was asked why he drank, he replied: “I drink because there is alcohol there.” (A very alcoholic-esque answer indeed.) However, the reason he first started drinking like a maniac is not entirely unrelated to the war. In Cheap Liquor Days, explains:

During the war (1942 onwards), my state of mind was actually the exact opposite. I mean, as to why I drank. I drank because there wasn’t any alcohol there.

Wartime and the period immediately after was a time when even the people who didn’t drink were all becoming drinkers. It’s not that everyone liked to drink—it’s that they had to drink even just to get by. And when you feel that you could die at any moment, it probably doesn’t matter a whole lot to you whether it’s methanol or ethanol that you’re drinking.

Conversely, even while it may not have the same momentum as it once did, Japan is still the 3rd greatest economic superpower in the world, and at least for now we live in peace. While it is no longer an era where the salaryman could just remain perpetually drunk without ever giving any thought to tomorrow, perhaps to lament that fact would be a bit of an overindulgence.