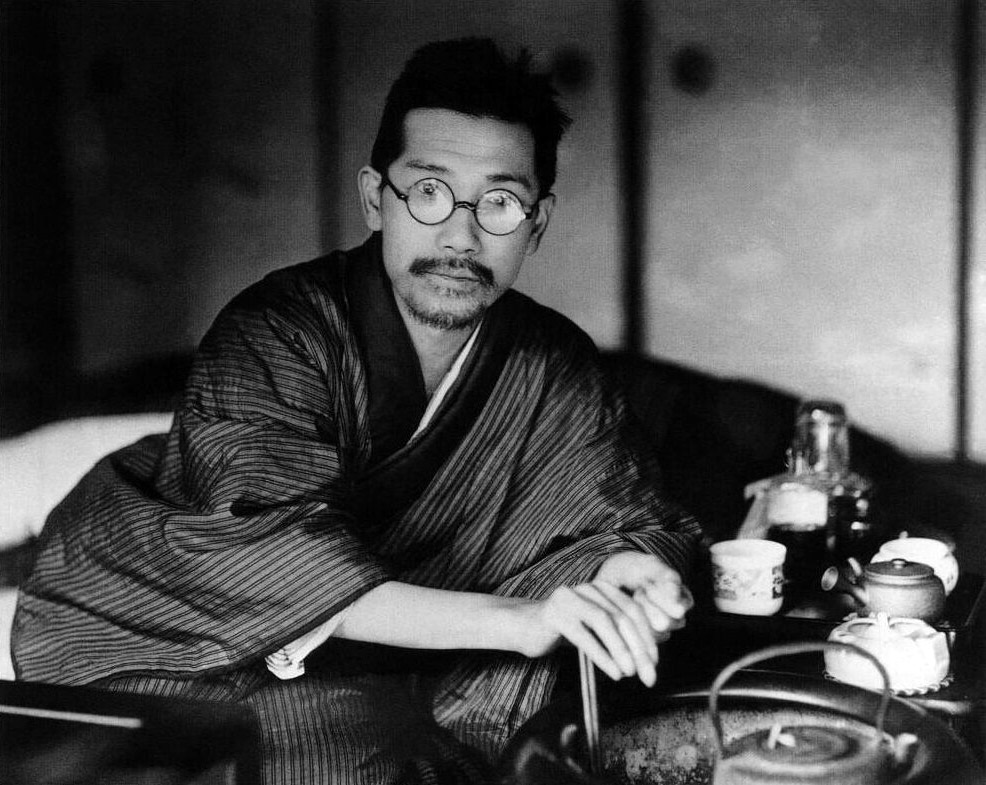

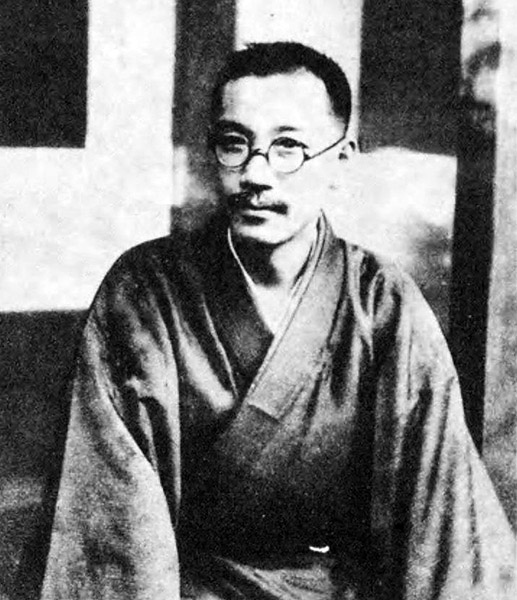

Kasai Zenzo

If you just try and keep drinking without a care in the world

Author | 16 January 1887 – 23 July 1928

Every organization has that one person who is funny to observe from afar, but a complete nuisance in close proximity. They get violent when drunk, knocking down beer bottles, covering themselves in vomit, and habitually exhibiting bizarre, eccentric behavior.

Author of numerous I-novels in the Taisho era (1912–1926), Kasai Zenzo—sometimes called the “Drunkard Author”—could surely be counted among these people.

But even if you’ve heard of him, not many among you will actually know any of his work by name. Some of his representative works include With the Children in Tow and Mourning Father. His work was always grounded in the negative aspects about himself: poverty, drunken frenzy, and illness. While some contemporaries such as Kikuchi Kan criticized his work, saying it was “not literature,” his self-deprecating writing style earned him many fans as well, especially among male students.

But in discussing Zenzo’s writing and his life, it is impossible to do so without also talking about his hardships. Even his breakthrough piece, With the Children in Tow, tells a story about poverty in which a father and his children wander the streets.

What, then, was the source of Zenzo’s hardship? Why was he so very poverty-stricken? Well, in his case, it’s not that he had no work. It’s that he wouldn’t work.

Reading the diaries of Kisaki Masaru, an editor at publisher Chuokoron-Shinsha, one gets a pretty good idea of just how unwilling to work Zenzo was.

Whenever Kisaki went to visit Zenzo at his house, he would almost always find him drinking. So badly did he perpetually reek of booze that even on the rare occasion he happened to not be drinking, it was hardly even something worth noting. (By the way, when Zenzo wasn’t drinking, he was often described as “lifeless.” But while he preferred to stay at home due to his love of solitude, when he drank, his hospitality would cause him to be in overly high spirits. His guests could then only wait patiently for the end of his one-man performances.)

Kisaki had commissioned Zenzo for a manuscript, and what with it being for a magazine, there was obviously a firm deadline. The problem, though, was that the second you took your eyes off him, he would be instantly drinking. Thus, Kisaki had to personally go over to Zenzo’s house first thing in the morning and keep watch of him until evening.

You would think if someone went this far for your sake, you would have to get on with it and start writing. But not so for Zenzo, oh no—still he refused to work. Persistent little bastard.

Not knowing when to leave well enough alone, Zenzo asked, “Could I please at least just have one cup?” Furthermore, even though Kisaki was literally standing right there, Zenzo’s neighbor suddenly barged in and suggested they start drinking, already beginning to make merry by himself. Shooting a quick glance at his editor, Zenzo then said, “Well, I suppose we can!,” as he started drinking and dancing. “The hell you can!,” Kisaki snapped. And who can blame him—anyone in his position would snap. Just how badly did this guy not want to work?

While Kisaki was in charge of other authors as well, because Zenzo was going to take advantage of any and every opportunity to start drinking, he could not afford to take his eyes off him. Thus, he ended up even having to spend that New Year’s Eve at Zenzo’s house.

Eventually, thanks to his efforts, Zenzo was able to complete the manuscript. But when someone had to be this diligent in babysitting the man, it was always a challenge to get any work done. In fact, there were other individuals who weren’t able to get that manuscript out of him.

When another editor was assigned to him, Kisaki said that it felt like “now someone else had to supervise his drinking.” But this other editor would actually bring Zenzo alcohol of his own accord. “I knew he would not write if he didn’t have alcohol, so each time I went over there, I had to bring a bottle with me.” It was not uncommon for them to then waste the day away by getting drunk together.

But it’s not that Zenzo had zero willingness to write. Once, when he was just first starting out, he left Tokyo and secluded himself in a hot spring resort in Nagano in an attempt to concentrate on his work. That’s all it was, however—an attempt. Replying to a postcard sent by his editor, he wrote, “The bath is good, the booze is good, the company is good, and the women are good,” making it difficult to say whether he really had any intention of working or not.

In the end, he never did get any writing done whatsoever.

Spending all his time in idle amusement, the lodging and entertainment expenses were piling up fast. The concerned editor thus gave some money to writer Kume Masao, a friend of Zenzo’s, asking him to bring the man back. But the pair ended up squandering the money on even more messing about, causing Kume to fall into debt, too. The birds of a feather really do flock together, it seems.

Because Zenzo was such a slow writer, he could not produce much. And because he could not produce much, he struggled to make ends meet. He left behind only about 60 works, all of them short, with only one of his works exceeding 100 pages.

In his final years he was constantly drunk, and so he would have to write through dictation. But it mattered not whether it was him or someone else doing the actual writing—progress was still just as slow.

Author Kiyama Shohei got to hear from one editor who took dictation from Zenzo. This story was recounted to him many times.

The booze-loving Zenzo began dictating to him over a drink. They started at around 3 PM, and finished around 3 AM. He went to the toilet several times while still dictating. He’d grind some ink and write these huge characters on Chinese paper…

When his dictation came to an end, he started crawling around on the tatami mat, pretending to be a dog that’s peeing, imitating a cow mooing… He’d rub his hands together to make grime… He’d suddenly start singing folk songs from his hometown…

(“Shinpen Nihon no Tabi Achikochi”)

A heaping serving of eccentric behavior, to-go. One can see how that’s a story you’d just want to keep telling over and over again.

The scary thing about Zenzo, though, is that this eccentric behavior was by no means a one-off event—it was an everyday occurrence. The “pretending to be a dog” bit especially was something he loved doing.

Author Kamura Isota, who assisted with the dictation, also wrote how after they’d finished writing two pages of a manuscript, Zenzo would be running around “in total ecstasy, completely naked inside that small room, on all fours barking like a dog.” You sometimes hear of people running around or being happy like dogs, but I don’t think many of us have seen people literally acting like one.

A grown man, crawling on all fours, happily woof-woofing away. Naked.

Even just the description of the act itself sounds rather horrifying. But when you consider how writing two pages was all it took for him to start acting like he was possessed… Something was very wrong with this man. It probably speaks to just how incapable he was of writing.

According to the aforementioned Kisaki diaries, by around 1925—three years before his death—practically no one would visit Zenzo at his home anymore, save for a colleague, author Tanizaki Seiji (younger brother of Tanizaki Junichiro), and some neighbors. It is probably no small number of people who had become estranged from him all because of his selfish, carefree way of life.

One of his victims, for instance, was future bestselling author Ishizaka Yujiro.

At one point in time, Zenzo was unable to afford the travel expenses to return from his hometown of Aomori. Thus, in order to make some money, he took some practice writings by Ishizaka—who was a student in the same town—and sent them to a publisher under his own name. Ironically enough, the newspapers gave this work rave reviews, saying, “Considering how dull all of Kasai’s recent work has been, this very good short story feels like a breath of fresh air from the author.” Poor Zenzo…

That’s not all. Zenzo had even dissed Ishizaka, telling him, “What the hell is wrong with you, making me read such vulgar, childish nonsense?!,” almost tearing his manuscript as he shouted at him. (Zenzo tried to tear up the manuscript, but he lacked the physical strength to succeed even at that. Again, poor Zenzo…)

Later, after Ishizaka had made a name for himself as an author, an editor asked him about Zenzo, and he reportedly turned pale and began shaking at the mere mention of his name. Even after his death, Ishizaka was never able to get Zenzo’s madness out of his mind.

Meanwhile, author Hirotsu Kazuo was good friends with Zenzo, to the extent that at one point they were even creating a fanzine together.

However, he then began to distance himself from Zenzo because of his work. Engaged in friendly rivalry, the fanzine’s authors would sometimes write stories based on each others’ private lives. Zenzo was very good at this, and he would tease his friends relentlessly.

One of his pieces featured Hirotsu. The piece tells a story about how Hirotsu had gotten his own wife’s younger sister pregnant and had then put the baby up for adoption. While the story itself was not true, the story’s foundation—Hirotsu’s womanizing ways—was. Helped by the strength of Zenzo’s writing, readers genuinely thought the man had gotten his wife’s sister pregnant, and Hirotsu was furious.

Back when Zenzo had been working with Kisaki, he had kept writing despite his poverty, not even having to resort to dictation. But by the time the Showa era (1926–1989) rolled around, the booze and his worsening lung disease had brought him to a point where his death now felt imminent.

By 1928, rumors about Zenzo’s worsening health were spreading, and friends and acquaintances were visiting him at his home. Hirotsu, too, hurried to see him when he was on the verge of death. The pair had momentarily reconciled, but by this time they were keeping their distance once more due to Zenzo including in his collection of writings the story that had initially caused their falling out. (This guy just didn’t learn, did he?)

At any rate, Hirotsu rushed to the scene as Zenzo was on death’s door. He asked to be left alone with him. Just when you thought this was going to be their big, emotional reconciliation, here is what Hirotsu said to the dying Zenzo.

“To tell you the truth, for the past month or so, I have been very angry with you. I honestly never thought I would see your face again for as long as I live. But then I spoke of this to someone else, and I suddenly felt that it wouldn’t be right if I didn’t also tell you. So that’s why I’m speaking to you now, because there’s no time.”

In other words, he was saying, “You piss me off so goddamn much that I never wanted to see your sorry face again, but then I heard you were going to die, so here I am.”

The average person might feel like that’s not the most appropriate thing to say to someone on their deathbed. But back in those days, writers always stuck to their beliefs no matter what—even if an old friend of theirs happened to be dying.

But although Zenzo was always making trouble, doing as he pleased, his funeral was attended by about 200 people, with 700 yen collected in condolence money. In today’s currency, that would be around seven million yen (USD$46,000). Aside from these donations, writer Sato Haruo and others pooled together a further 316 yen in donations for the bereaved family.

Kasai had been a lousy drunk, yes. But his simple and easygoing nature had also made him lots of secret admirers, both in and outside the literary circles.

One liquor shop owner who had been friendly with Zenzo, upon hearing of the many people mourning his death, said with pride in his chest, “Gathering as much as 700 yen in condolence money… Kasai-sensei truly was a great man.” The shop owner had been supplying Zenzo with an endless flow of booze, putting it all on his tab, and even after Zenzo’s death he did not ask to be reimbursed. (Zenzo’s tab, by the way, had been equivalent to the 700 yen collected in condolence money. This man drank too much.)

While many books have presented the above anecdote as a seemingly heart-warming story, I kind of can’t help but feel like this “kindness” shown by the shop owner is exactly what created Zenzo’s perpetually liquor-soaked existence. I don’t know, maybe it’s just my imagination…

In any case, despite Zenzo’s broken personality and lifestyle, it is clear that many authors had respect for him. According to his friend Tanizaki, even the dictation in his later years was something he only did reluctantly because he had to make a living. And indeed, while he would start barking like a dog after writing just two pages of a manuscript, when he would find those pages the next morning once he’d sobered up, he would tear them up and throw them away. Even here we can see glimpses of Zenzo’s pride as a writer.

It is often said that a person is judged by the manner in which they die.

The fact, then, that you could potentially get drunk and start barking like a dog on all fours while stark naked, and still there would be a large crowd of people there to mourn your death anyway? Surely that would be a wonderful ending to one’s life.

It is an encouraging story for all the drunkards out there who frequently find themselves covered in vomit and soaked in blood. But, of course, all of that is permissible only on one condition: you have to actually have some talent.