Fujiwara Toshio

If you feel like drinking for eight hours every day

Kickboxer | 3 March 1948 –

From the late 1960s to the early 70s, the Japanese Islands were captivated by a kickboxing boom.

Sawamura Tadashi, the central figure of this craze, was known as “The Demon of Kickboxing.” He was the equivalent to baseball’s Oh Sadaharu and Nagashima Shigeo, or sumo wrestling’s Taiho—a role model for children all over the country.

Sawamura even debuted as a recording artist, gracing the covers of boys’ magazines. It seems somewhat unsettling now, looking back, to imagine some guy with a beard and a crew cut smiling on magazine covers, but so great was Sawamura’s popularity that no one gave it a second thought. Even in the 1980s when I was a grade schooler, the “Vacuum Jump Knee Kick”—Sawamura’s classic move—had still not become an obsolete word, and kids were always imitating him in the hallways. (Although it may have been a strange phenomenon that was endemic only to the Nerima Ward in the outskirts of Tokyo.)

It was due to kickboxing boasting such popularity that then led to the constant mergings and dissolvings of its various organizations, ultimately causing the sport to disappear from the social stage. Right around the final phase of this boom, however, there was another character who made his entrance: Fujiwara Toshio.

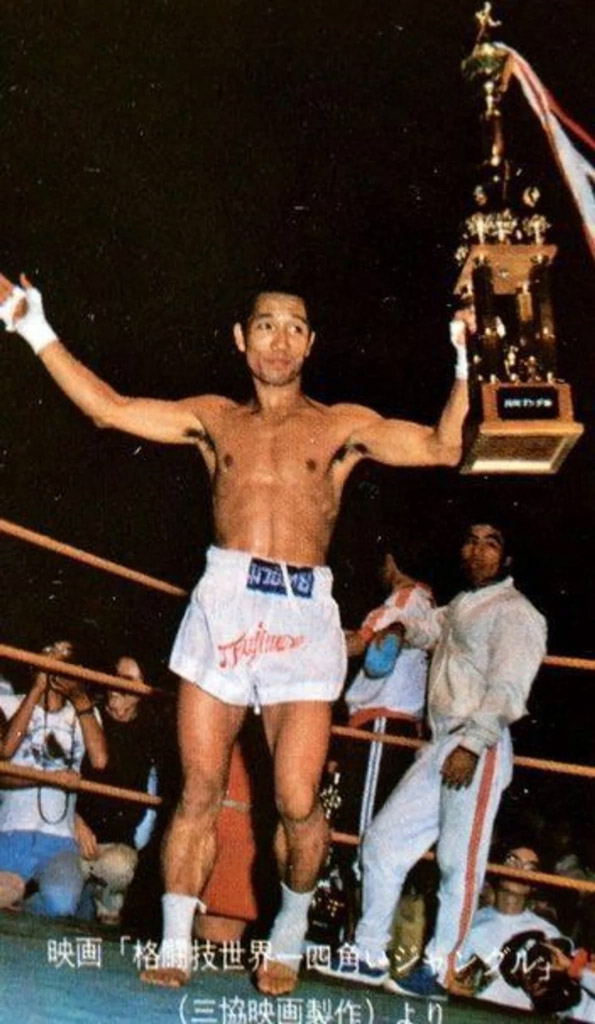

Fujiwara first joined a gym in 1969 at age 21. In 1971, he won the inaugural All Japan Kickboxing Association Lightweight title. In 1974, he had a high-profile fight against former pro boxing world champion Saijo “Cinderella Boy” Shozo. But it was in 1978 that he cemented his reputation as a kickboxer of legendary renown. Winning by KO against Thailand’s Mongsawan Lukchangmai, he took the title of Rajadamnern Stadium Lightweight, thus becoming the first foreign champion in Muay Thai’s 500-year history.

It may be difficult for Japanese readers to understand the significance, but this really was a tremendous achievement. Even today, Fujiwara is treated in Thailand like a guest of the state, with red carpet rolled out for him at the airport while he just walks through customs. It is even said that Rickson Gracie—a living legend if there ever was one, known as the “undefeated martial artist with 400 fights“—once spotted Fujiwara from a distance and ran straight over to him just to say hello.

There are more than a few individuals who are recognized overseas and yet underrated domestically. Fujiwara is one of these people. Unfortunately, in his case, the time just wasn’t right. In 1978, when Fujiwara became the first-ever foreign Muay Thai champion, Sawamura Tadashi was already a thing of the past. At the same time, it was also much too early for him to catch on as part of the unprecedented martial arts boom that was to come in the 1990s.

But now, having read this far, the more perceptive readers among you may have noticed something. We have just spent 500 words or so discussing something that involves not one drop of alcohol.

“You’re just going on and on about kickboxing trends! There’s no way this story’s going to end up in this guy getting fucked-up!” So far in this book, I have shared with you stories about eminent figures getting besotted, hitting people, being thrown in the drunk tank, and otherwise violating public order and morals. I feel like I can now hear some of you going, “What the hell, man? The discrepancy is too much!”

But worry not, dear reader, for Fujiwara is a legitimate, bona fide, honest-to-god drunk.

Here is something from the book Yoshida Go no Karate Baka Ichidai to give you a taste.

— How much do you tend to drink?

Fujiwara: On average, I’m drinking ten hours.

— Huh? How many times a week is that?

Fujiwara: Every day.

Ten hours every day. That’s about the same as the sleeping hours of a two-year-old.

He adds that he starts drinking every day from noon. In an issue of Nikkan SPA!, they write, “We met for the interview at a pub. He was simultaneously drinking three strong highballs, and after drinking for eight hours straight, he looked completely fine.” Now that’s impressive.

But let’s get back to the interview.

— Have you ever had any failures with alcohol?

Fujiwara: Most of my failures involve alcohol. Even though these days I no longer pick fights or use violent language, I’ve been told that people are too scared to approach me. They must have heard the rumors about me and Sayama (author’s note: Sayama Satoru, the original Tiger Mask) going on all those rampages.

They “must have,” yes. People not being able to approach a guy who’s just drinking in peace—exactly how frightening is he? What is he, Wada Akiko?

Fujiwara, who spends nearly half his day, every day, marinated in booze, also has something quite poignant to say.

I drink hard.

I work hard, I practice hard, I drink hard, I court women hard… 100% doesn’t cut it. If you don’t give everything 101% or more, there’s no way you’re going to win against your opponent, and what’s more is that you don’t even get excited about what it is you’re doing.

Damn, that is cool. That is absurdly cool.

But wait a minute… If you were to drink every day at full strength, at 101%, that means that ten days later the percentage would be up by 10.5%, and twenty days later by 22%. The body can’t take that amount of punishment! If you were pushing yourself to the limit every day like that, wouldn’t your body be crying out for sweet relief?

The interviewer asks Fujiwara the following.

— Do you ever get hangovers?

Fujiwara: You don’t get hungover if you drink like your life depends on it. It’s when you drink reluctantly that hangovers happen.

It’s like he’s in a state where he’s capable of anything as long as he has the energy. I feel like if a normal person was to try doing the same, the more they drank the worse it would be the next morning. Maybe they’re just not taking their drinking seriously enough…

Fujiwara can blow away hangovers with sheer determination alone. But when he was still active, he maintained a very a stoic lifestyle. Expecting to read a book about one seriously thirsty soul, I picked up Fujiwara’s autobiography, Shinken Shoubu: Tatakai no Shinjitsu, only to discover that this was a book involving not one drop of alcohol. But then I suppose it should come as no surprise.

When he was active, drinking and smoking were strictly prohibited. You will be surprised to learn just how thorough that prohibition was.

Many times it happened that I needed to urinate in the middle of training but I wasn’t allowed to go to the toilet, so I would just piss myself right there as I kept kicking the sandbag. There would be blood in my urine because I was training so hard. That was an everyday occurrence.

I trained hard, 365 days a year. Of course, whenever I had a match coming up, I would regulate myself starting from three days before the fight. But as soon as the match was over, unless I had taken serious damage, it would be right back to training the very next day.

An article in Gendai Business also tells us that he would only have “about three days off a year,” and that he would usually practice “around ten hours a day.”

These days, he instead spends ten hours a day—365 days a year—soaked in alcohol. But in the past, he was spending the same amount of time on training. He has said that he was training so much, even his muscles began to rot.

It was a strict, hierarchical relationship, one in which the master’s word was absolute. Fujiwara’s private life was thoroughly controlled, and whenever he went out, he had to report about every single thing he did. “I am now going to the greengrocer’s.” “I have finished shopping and will now return to the dojo.” “I will now head to the bathhouse.” “I have just arrived at the bathhouse.” “I got out of the bath just now.”

And the rule was that training was never over until the master said it was so. Fujiwara remembers feeling rather troubled one time when his master suddenly left to go out drinking in the middle of their training session. Had Fujiwara decided on his own to quit training for the day and head home, his master would have been furious when he returned. Thus, he had no choice but to keep training until dawn.

The master who disappears during practice and never returns, and the apprentice who just keeps going anyway… It feels like neither individual is quite right in the head.

I mean, you would have to keep kicking that sandbag until you lost consciousness. Even me, I don’t know how many times I came close to passing out. I was always in this half-conscious state as I just kept hitting the bag.

Booze could never bring Fujiwara to the edge of unconsciousness—only training could.

But it wasn’t just the length of these sessions. It was also his dreadful training menu.

One day, Fujiwara thought to himself, “Wait, why don’t I just build a body that it hurts to kick?” He thus got to work at strengthening his shins. He started out by kicking a tire, but once he’d gotten used to doing that, he began kicking an iron pole.

While it feels like there is a world of difference between kicking a tire and kicking a literal iron pole, that is nevertheless what he did. As a result, he ended up building himself shins that were as strong as steel.

Kickboxer Peter Aerts, who took the world by storm in K-1, went to visit Fujiwara at his gym. He asked him what sort of training he used to do back when he was still fighting. Fujiwara demonstrated by kicking an iron pole, reportedly leaving his guest lost for words.

And Peter Aerts was right to feel that way. While Fujiwara says it is this training method that made him a kickboxer that would go down in history, it really is just much too drastic, no matter which way you look at it.

After his retirement, Fujiwara worked as a golf course manager, and then began running a kickboxing gym. While he is famous within the industry for his constant drinking, he has at the same time continued to foster the next generation of fighters, and he also organizes an annual event, the “Fujiwara Festival,” where he takes on pro wrestlers among others.

In 2007, he was at risk of losing his right leg, and he was having difficulty walking. One year after his operation, however, he was back in the ring. While the people around him thought him to be reckless, he had reduced his drinking, and he had put in the work. Even now, after his retirement, this man is far more than a mere heavy drinker.

Whether you’re a sports athlete or a salaryman, there are times when you must stand your ground. Conversely, if you are capable of standing your ground in those moments without being tempted to turn to booze, then perhaps in the less critical moments of life you are allowed to drink as much as you like—even if it is ten hours a day.

If you’re going to do something, do it all the way. In the long run, life is all about balance. Although, when it’s me saying this, I’m afraid it might sound like the self-justifications of a drunk trying to hide his guilty conscience about drinking day in and day out…