Here are two magazine interviews with Shin Rizumu about his 2022 full-length album Música Popular Japonesa. The first one discusses mainly his roots and musical upbringing, while the second one is focused more specifically on this album and what Shin Rizumu is up to nowadays.

The first interview is from the March 2023 issue of Record Collectors’ Magazine, and the second interview is from the December 2022 issue of Musica.

Interview & text: Shibasaki Yuji (first interview), Ariizumi Tomoko (second interview)

English translation: Henkka

Shin Rizumu: Website, Twitter, Instagram, YouTube

Note: You can buy this album on CDJapan.

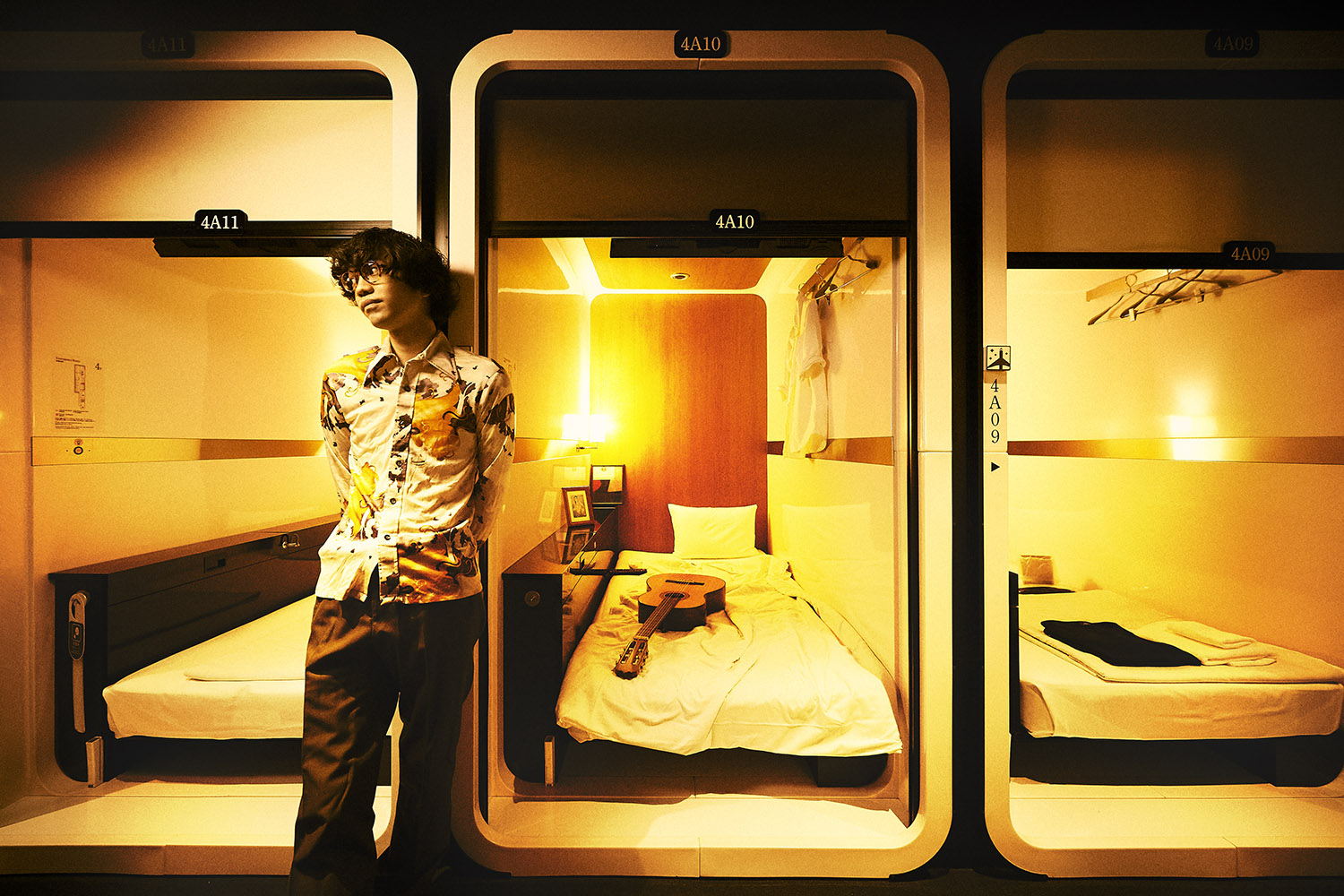

Shin Rizumu made his sensational debut in 2015 as a home-recording singer-songwriter who was only a high school student at the time. Aside from composing all the music and writing all the lyrics, he also worked on the arrangements, recorded all the instruments, and even did the mixing himself.

His first album—a natural mix of various musical elements, including yesteryear’s soul music and AOR, neo acoustic, and guitar pop—presented a kind of hybrid pop style of shockingly high quality. In addition to a certain sense of precocity, his biggest appeal was his fresh, lively sound that was very much of the new era, as well as his brilliant lyrical worlds. In 2017, he released his second album—the masterpiece Have Fun—which resonated even with other, globally renowned home-recording artists of the time, further showcasing the evolution of his talent.

Listeners had to wait five and half years for another album until finally, in November of last year, this new album was released. After writing songs for people like Fujii Takashi and Nakajima Megumi, becoming a supporting musician for acts like Kirinji and Hata Motohiro, and collaborating with Ryusenkei, the growth and self-confidence he has gained as an artist can be seen even in the bold title of his new album: Música Popular Japonesa. That is to say, his intention was to take Brazil’s “Música Popular Brasileira” (MPB) and adapt it into Japanese-language pop music—MPJ. While it may seem like a bit of a dramatic statement to make, the album’s content does not fall short of its title in the least. To the contrary, it’s truly a fantastic album—the kind of material that is likely to impress especially the more devoted MPB fans.

Now, already carrying the air of something like a maestro at the young age of 25, we asked Shin Rizumu about his musical history and about what kinds of music he is interested in these days.

Shin Rizumu: Although I had listened to things like anime theme songs and J-pop before, I was actually a bit slow in becoming interested in music—it took me until the later years of elementary school for that to happen.

I had this classmate and we both liked the same manga, and his father happened to be a big music fan. Through talking with him, I came to learn about the apparent existence of something called “Western music.” (laughs) I became very curious to hear exactly what it was for myself. My own father was also a pretty big music fan—in his youth he’d even been making music of his own on the synthesizer—so I began asking him questions about music, too.

Right around the same time, they had this Style Council best-of album on display at our local Tower Records, so I gave it a listen on the trial listening machine, liked what I heard, and I bought the album. The first song of theirs I heard was “Shout To The Top.” It was so catchy, and even as a child I was just instantly captivated.

It was once Shin Rizumu was in middle school that musical instruments entered the picture.

Shin Rizumu: I joined our school brass brand club and started playing the trombone, and I also began playing electric bass as a hobby. My father then started recommending me all these songs. “Why don’t you try covering this on the bass?”

But although my dad is a music fan, he’s the type who would never recommend me anything before I actually showed an interest in the thing. The moment he noticed that I was beginning to show an interest in music, it’s like the floodgates were opened and he started bombarding me with his stockpile of recommendations that he’d built up over the years. (laughs) We did have a record player at home, but it was broken, and even CD players take a bit of effort to use, so instead he just began hammering me with his recommendations using YouTube. It was information overload—I could hardly even keep up. (laughs)

After you learn a phrase once, it’s no longer that difficult. So I started out by covering songs with catchy bass riffs—stuff like Elvis Costello‘s “Pump It Up.” Then, once I got a little bit better, I was given more difficult material to play, like The Jackson 5 and Stevie Wonder. I’d give that stuff a try, but since I was only a beginner, it was so, so difficult… I felt like I’d hit a wall—I almost gave up. But then my father said, “If you give up now, then your music life ends right here.” That really lit a fire in me. (laughs) When he said that, I just went, “God dammit!,” and I started practicing those songs as if my life depended on it.

I’ve always liked Stevie Wonder ever since then, and I still listen to his music often. The first cover of his that I did was “Sir Duke,” and my favorite album is Songs in the Key of Life. His music is just so pop, and his melodies grab you from the moment you first hear them. His arrangements, too, are just overflowing with this sense of play, and that kind of thing is something that I would think has been an influence on me personally.

With the bass, I was mostly learning songs by ear. But already back then you could find all kinds of videos on YouTube—you could just type in the name of the song and the word “bass,” and for a lot of songs you could find instructional videos that showed the fingerings as the song played. I’d watch those and play along, like, “So… Something like this?” Then, around six months after I’d first picked up the bass, I started playing the guitar as well, and gradually I came to try out all sorts of different instruments.

Shin Rizumu was a young boy single-mindedly devoted to mastering his musical instruments. But hearing how he himself describes it, you don’t get the feeling that he was actually very stoic about practice—if anything, he makes it sound like he took it pretty non-seriously.

Shin Rizumu: I was never thinking, you know, “I’m gonna master this instrument!” I’d always liked video games, and so for me, whether it was covering a new song or learning a new instrument, it felt similar to clearing a new stage in a video game. To me it felt very laid-back; like I was just trying out one game after the other.

When it came to my father’s recommendations, while some of them were the sort of super demanding, Guitar Hero-esque songs, I feel like most of them were actually the type that were just overall fascinating to me music-wise. One example that especially left an impression on me was Aztec Camera. In terms of their discography, their debut album, High Land, Hard Rain, and their third album, Love, were ones that I listened to a lot. Also, Haircut One Hundred‘s album Pelican West.

While learning to play the bass, I also began gradually listening to AOR stuff, too. I started with a lot of slapping practice, trying to learn Steely Dan‘s “Peg.” From there, I was also listening to Michael Franks‘ albums a lot—I was totally drawn to that gentle singing voice of his.

At the same time, I was also being introduced to Japanese music which I similarly started listening to because I just liked what I heard. I started with SUGAR BABE, followed by the solo albums of Yamashita Tatsuro and Onuki Taeko, and so on… From there, I also came to know of Kirinji. It was like, “Wow, there’s people in Japan making music like this even today!” I was totally hooked. I remember when SUPER VIEW came out in 2010*—that was the first album of theirs that I bought in real time. I had it pre-ordered, and I went to pick it up straight after school, feeling all excited.

(* Note: SUPER VIEW actually came out in 2012, while the album BUOYANCY came out in 2010.)

In his third year of junior high school, Shin Rizumu began writing his own songs.

Shin Rizumu: This, too, was because of my father’s suggestion. (laughs) I started out making music on the computer. The stuff I wrote back then was all totally influenced by Aztec Camera and that sort of neo acoustic/guitar pop kind of thing.

By my first grade of high school, I’d written around five songs of my own, so I burned them on a CD-R and made my own mini-album. Back then I knew nothing about things like distribution—I had the wrong idea that you were supposed to directly go to stores yourself and have them sell your CD, so I went to like Tower Records and Village Vanguard, asking if they would put my CD up on their shelves. (laughs) Naturally, they would not.

The only place that did was my local Shimamura Music—they had an indie consignment board at the store, and they agreed to take my CD. I uploaded the same audio on SoundCloud, and I was then approached by a label after they’d heard that audio, leading to the release of the Shinri no Mori 7-inch and my first album.

When I released my first album, many listeners and writers were drawing parallels between me and Ozawa Kenji and Shibuya-kei music, but at the time I had never listened to either Ozawa Kenji’s solo works or Flipper’s Guitar. If anything, I was mostly just listening to that ’80s neo acoustic stuff, as well as this modern era Italian band—who were actually probably influenced by Shibuya-kei—called Fitness Forever. I was listening to them constantly, especially their first album, Personal Train, which I discovered through my YouTube recommendations. Their songs and arrangements are just so colorful. I really dig them.

It’s interesting to note that despite Shin Rizumu’s Shibuya-kei roots and influences, he overlooked the actual “originators” of the genre. To look at it from a different angle, however, perhaps that it is how his music has avoided being labeled under any one genre ever since he first made his debut.

Shin Rizumu: I only started listening to Ozawa Kenji’s solo material after that. I was especially hooked on the albums LIFE and Kyuutai no Kanaderu Ongaku. On my second album, Have Fun, there’s a song (“Haru no Niji“) where I quote one of his song titles and directly pay homage to him.

Around this time, I was constantly listening to home-recorded multitrack stuff by pop and indie rock bands of my era. Stuff like Vulfpeck, The Lemon Twigs… I was particularly influenced by The Lemon Twigs. Album-wise, especially their 2016 release Do Hollywood. I just love how many elements you can hear even within one individual song of theirs—they just keep coming. I think it was because of their influence that Have Fun has some of those more alternative type songs.

Through their producer, Jonathan Rado, I also came to know Foxygen, and soon I was listening to bands like Temples and Tame Impala… I had so much fun just discovering all these different indie rock bands.

As stated in the opening of this interview, on Música Popular Japonesa—Shin Rizumu’s first new album in five years—he is suddenly much closer to Brazilian music. We were curious to know about the particulars.

Shin Rizumu: It’s actually not that I suddenly went through another Brazilian music phase or anything. Rather, we’re back to talking about my father again… (laughs)

When I was little, there was this album that he apparently used to play for me all the time to make me stop crying. Of course, I had no memory of it myself, but then later I was drawn to the cover of Orlandivo‘s self-titled album when I happened to notice the CD in my father’s collection, and he told me the story. When he did, it suddenly felt like those songs were somehow already etched in the depths of my mind somewhere, you know? (laughs) It was around that time that I started listening to all kinds of Brazilian music.

Maybe it’s because of my childhood memories… All those unexpected, seemingly abstruse melodies and chord progressions you often get with MPB, I was already accustomed to hearing them. Even with the very first songs I wrote I was always using slightly unusual chord progressions, so maybe there was already a bit of unconscious influence there. But at the same time, I’d never written anything where it felt like I had fully digested those MPB elements and channeled them into my own writing. It’s like I had some kind of a resistance to doing so, or like, I felt like I wasn’t yet capable of doing it. And so that’s why I never even really attempted it.

Later, back in 2020 when I was spending more time at home due to COVID, I felt like trying something I hadn’t done before. I made a digital-only EP, and I ended up writing a few songs for it in which I consciously incorporated those MPB elements. I was personally pleased with how those songs came out and I received positive feedback from people who heard them, and that’s what made me decide to go all-out and make this album. Using as hints all my favorite MPB songs I’d heard up until now, I channeled them into my own pop originals.

Along with the aforementioned Orlandivo album, Shin Rizumu says he was also particularly taken with the works of the great João Donato.

Shin Rizumu: In his sound production, there are always so many different sounds interchanging or alternating. His drum sound is so distinctive, too. The lows are cut-off so it just sounds so light—“splish-splash!”—and yet it’s also got such a strong core to it. While I do have the strongest emotional attachment to Orlandivo’s album, I have to say that João Donato‘s solo work—beginning with albums like Quem é quem and Lugar comum—really is great. It’s incredible how he’s active even now, almost at the age of 90. Of his more recent works, I also like the electro-boogie album Sintetizamor that he made with his son Donatinho.

And he’s got such a great voice, too—I feel like there are some similarities between him and Michael Franks. It’s not like he’s got incredible range or anything, and his singing is soft, but it’s like his voice has just got this persuasive power to it… In a similar sense, Hosono Haruomi is another singer I also really like.

Speaking about the sources of inspiration for this album, I also have to mention Gilberto Gil. Album-wise, Luar (A gente precisa ver o luar) and especially the track “Palco“ were something I very much used as a reference—you’ll immediately hear what I mean if you listen to it. (laughs) It’s such a pleasant album, sounding all glittery and pop by keeping pace with the AOR and disco sounds of the era. It’s got that “sparkle” about it that’s really one of the characteristics of Brazilian music of that whole period.

As for female singers, I also like Rita Lee. But rather than the generally highly rated psychedelic-leaning stuff, right now I’m more a fan of her dance music albums of the early ’80s. Honestly, I recently find myself thinking that, generally speaking, I especially seem to enjoy the tonal textures of the late ’70s to the ’80s.

Shin Rizumu says that he is also becoming more interested in vintage synthesizers as of late.

Shin Rizumu: This album called 106 by Louis Cole collaborator Jacob Mann is so fun. He’s someone who usually does big band arrangements and that kind of thing, but on this album, everything beginning with the rhythm section was constructed with this ’80s analog synthesizer called Juno-106. It’s so inspiring—there’s nothing else out there that sounds quite like it.

(Interview conducted in Tameike-sanno on 13 January 2023.)

— It really is a great album. Even in your teens you always had such an astounding musical knowledge, but now it’s like you have polished and refined your skills and sensitivities even further, making for some truly fantastic, fresh-sounding pop music. First, I wanted to ask: what were the previous five years like for you?

Shin Rizumu: On this album, I did almost everything by myself. Ever since my second album, I had been in this Lemon Twigs and Vulfpeck state of mind—meaning, artists who do everything themselves, from recording to mixing and everything else. That to me is so cool, and I wanted to learn how to do all that myself. I had been studying that kind of thing in university as well, and so all the songs that I’ve released for streaming since then, I was making them sort of as a challenge to myself. It was me just learning through constant trial and error.

At the same time, I was also a supporting musician and I was doing arranging work, and that too afforded me lots of learning opportunities. Through my performance work as a guitarist, I got to explore such a wide range of sound design, working with other people. Through my arranging work, I of course had to make all the sheet music myself, and I also learned a lot about things directly related to engineering and producing—like, what kind of a sound you’re going to get working at this particular studio with this particular engineer.

While I was gradually learning about all these little things, I was also improving my home recording environment by upgrading my equipment. I then released an EP two years ago at which point I thought I was pretty close to the sound I was trying to get, and I started to feel that with a bit more work I might be able to put out an album. After updating my setup even more and after even more on-location trial and error, someone happened to approach me about the possibility of releasing a new album, and I decided to put everything I’d learned to the test and give it a go. That was the past five years for me.

— So, in other words, it was a kind apprenticeship period for getting you to the level where you needed to be in regards to recording music all by yourself?

Shin Rizumu: That’s how it turned out, yes.

— Listening to your explanation, am I understanding you correctly in that you recorded everything on the album yourself?

Shin Rizumu: Everything apart from the string instruments was recorded at home. On the EP, I did play even all the trumpet and flute parts, but the range of what I can actually do with those instruments is limited by my lack of ability, meaning I’d have to arrange within those limits—not to mention that it also takes a painfully long time for me to record those parts myself. So for those instruments, I did ask others for help.

Also, Kanesaka Yuki plays keyboards on “Aitsu no LIFE,” Wakui Sara plays keyboards on “Harebutai,” and Hashimoto Genki plays drums on “Harebutai” and “MPJ.” Other than that, it’s all me. My concept when writing “Harebutai” was that it’d be sort of like the Antônio Loureiro type of modern Brazilian music influenced by modern jazz, mixed with J-pop. I’d already decided I was going to ask Hashimoto to play on it, and I was planning on playing the keyboards myself, but then I happened to become acquainted with Risa and so I just asked her to do it.

— I see. The arrangements, performances, even the mixing—everything sounds amazing.

Shin Rizumu: Thank you. For me though, there are still parts in there that I feel I could have refined more. (laughs) Going forward, I feel like if I can hone my abilities to make home recordings that sound even more like studio recordings, it’s going to allow me to broaden my musical scope as well. Especially with the string arrangements, I feel like there’s so much more that I still need to learn. Still, I think I did alright with this challenge.

— The album is titled Música Popular Japonesa, an intentional pun on Música Popular Brasileira (MPB) which refers to post-bossa nova popular music from Brazil. While MPB has a rich history, there is at the same time also this emerging new generation—led by people such as the aforementioned Antônio Loureiro—which draws upon jazz music, and we have been getting lots of interesting new music in recent years. To me it feels like even in Japan we’ve been seeing more young artists who are influenced by that sort of thing.

Shin Rizumu: Right. Recently there’s been a lot of jazz musicians in Japan getting into the whole vocal-centered J-pop realm, so in that sense I can feel similarities between us and the current Brazilian music scene. For me, ever since my first album I’d always been more or less conscious of jazz modality when making vocal music, and on this album I think it’s even more obvious.

From the beginning, thanks to my father’s influence, I’d always been listening to stuff like João Donato ever since I was little, and thus the whole sound of MPB; the melody progressions; the harmonic feel—it always felt pleasant to me. So in my mind, I’d always had those influences in my music ever since my first album, at least to some extent, and just thinking about the chronology of my releases, I always wanted to make an album with MPB as its concept just as soon as I was capable of making it.

The problem is that I never did feel like I was proficient enough. Even when I started making this album, there were still things about it that I didn’t feel I could arrange to my complete satisfaction. But to be fair, knowing my own personality, I could keep studying forever and still never feel like I’m good enough.

— Probably, yeah. (laughs)

Shin Rizumu: I was thinking once I hit 30 or 40, then I could finally make something that sounds refined enough. But that “freshness” thing you mentioned at the beginning of this discussion, or like… Well, I felt like if I just went ahead and tried making this album specifically at age 24 or 25, it would be something different. I had no idea how it would actually turn out, but I just made up my mind that I wanted to take on this challenge of making an album with MPB as the concept.

— While “Flavor of lie” is a song with a breezy samba beat, the lyrics are an antithesis to the trends of modern society. What was your vision for this song?

Shin Rizumu: “Flavor of lie” and “Kurashi no Hanbun” are songs that were already on the EP that I released two years ago, and sound-wise they really haven’t changed much. In terms of my mindset at the time, it was like I was starting on a big, new challenge for myself. As for the lyrics, since it was during COVID and we were hearing all these gloomy news all the time, I guess I wanted to make that the theme.

I think the only songs I’d done before this one that had a cool, black music-influenced sound were “Houninshugi” and “Shohousen” from my first album, but I’m not satisfied with the lyrics I wrote for those songs. So that was another theme for this album—the songs on the second half of the album have that black music kind of taste to them.

— With lyrics like “samayou hibi no yoake / nanimono na no ka tou na” (“dawn of my wandering days / ask not who I am“) in “Harebutai” and the lyrics of the last song “Palette,” your inner feelings are very much apparent here.

Shin Rizumu: Yeah, I think “Palette” really shows an honest side of myself. And I wrote “Harebutai” with the intention that it would link to “Palette,” so maybe that’s why.

— With “Flavor of lie” being just one example, I feel like on this album you’re singing about what you actually want to sing as a singer-songwriter, even more so than before.

Shin Rizumu: True… I feel like on tracks 6 through 8, I took all the negative emotions I have—you know, the “To hell with the world!” kind of sentiment—and channeled it into those songs. And the reason I made “Palette” the last song is because I strongly felt that I wanted the song that most conveys how I feel at this exact moment to bookend the album.

— “Itsumo samayotterun da / kako no kui wo” (“Forever wandering / through past regrets“), “kurikaesu yoru ni / douka yamanaide” (“please don’t lose yourself / amid these repeating nights“), “doko made demo egakeru ka / samenai jinsei wo” (“how long can I keep sketching out a life / that never loses its fire?“)—you’re singing all these very heartfelt words in this song. How did these feelings surface?

Shin Rizumu: When I look back on my life, there are things that I regret; things that I think I should’ve done differently, and I’ve even wasted periods of my life dwelling on these past regrets.

But now, after having put myself in all these new environments, doing all sorts of different things, and through making this album, I’ve come to think that maybe even those choices weren’t actually mistakes. Now, after some time has passed, there are things that make me think that even those choices were actually good—seeing as I’m able to do fun things right now, then maybe it’s all okay.

So in making this song, it’s kind of like I wanted to write a message to my future self, so as to say: if I ever feel like looking back on my life and dwelling on past regrets again, just remember this. And it’s not only me, either—I’m sure there’s lots of people who have made mistakes who are now living their lives while clinging to those regrets; people who are struggling with those feelings right now, in real time. Taking all that into account, I feel like as long as you’re having fun right now, then maybe it’s alright to embrace that… That’s the sort of message I wanted to put into this work.

— I’m sure these past five years you have been wrestling with regret and self-conflict as you have kept experimenting through trial and error. But the fact that that struggle is what led to a musical work of this quality, I think that above all is what makes this song so convincing.

Shin Rizumu: I’m glad to hear you say that. I will keep striving to do my best.