Kajiwara Ikki

If you’re just drinking, when suddenly you’re under arrest!

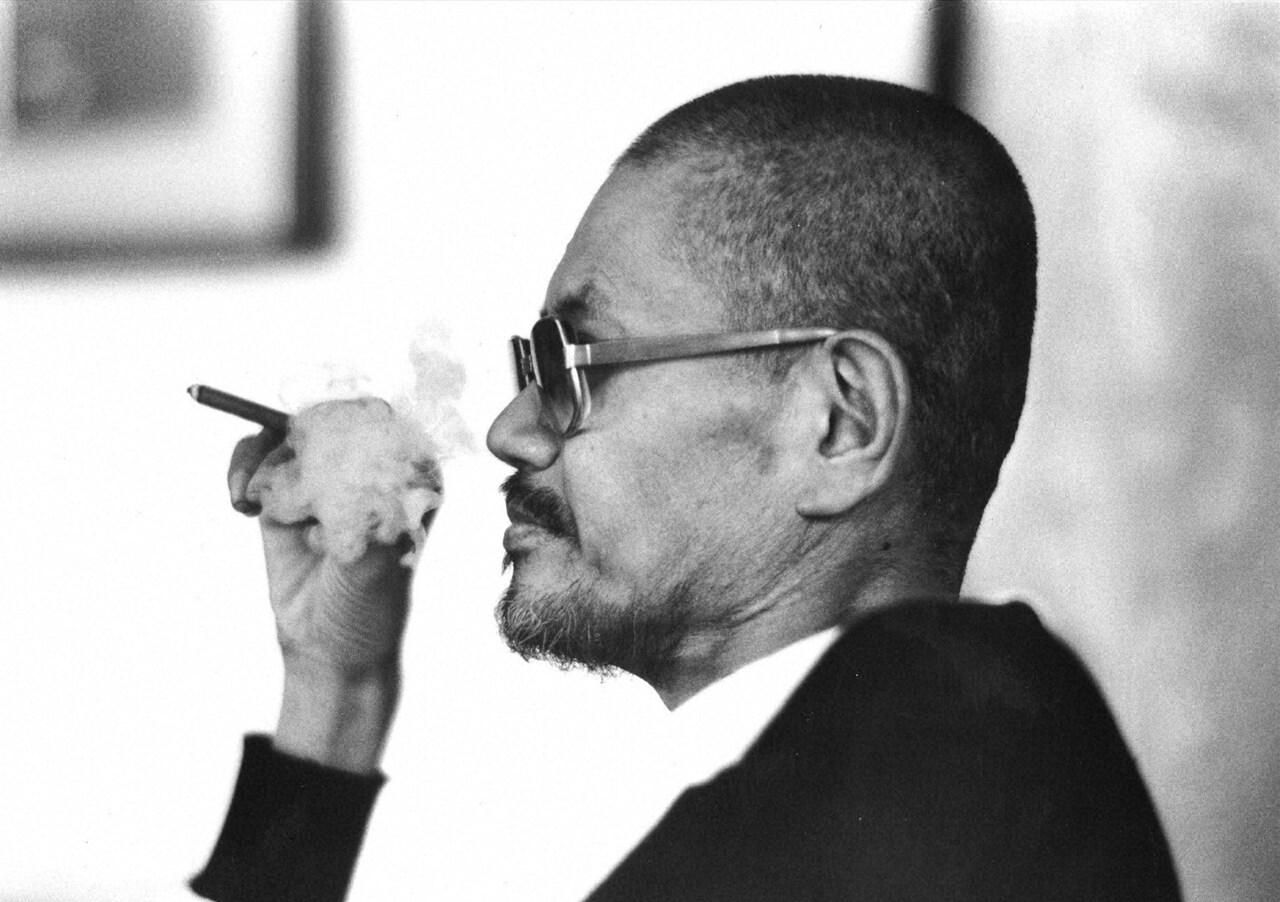

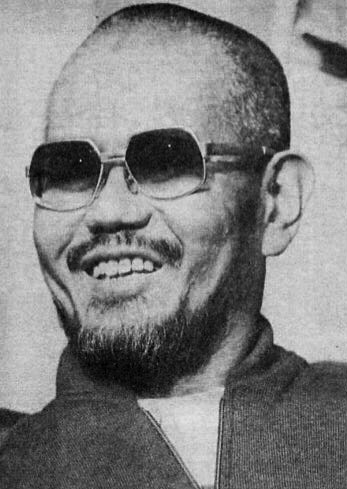

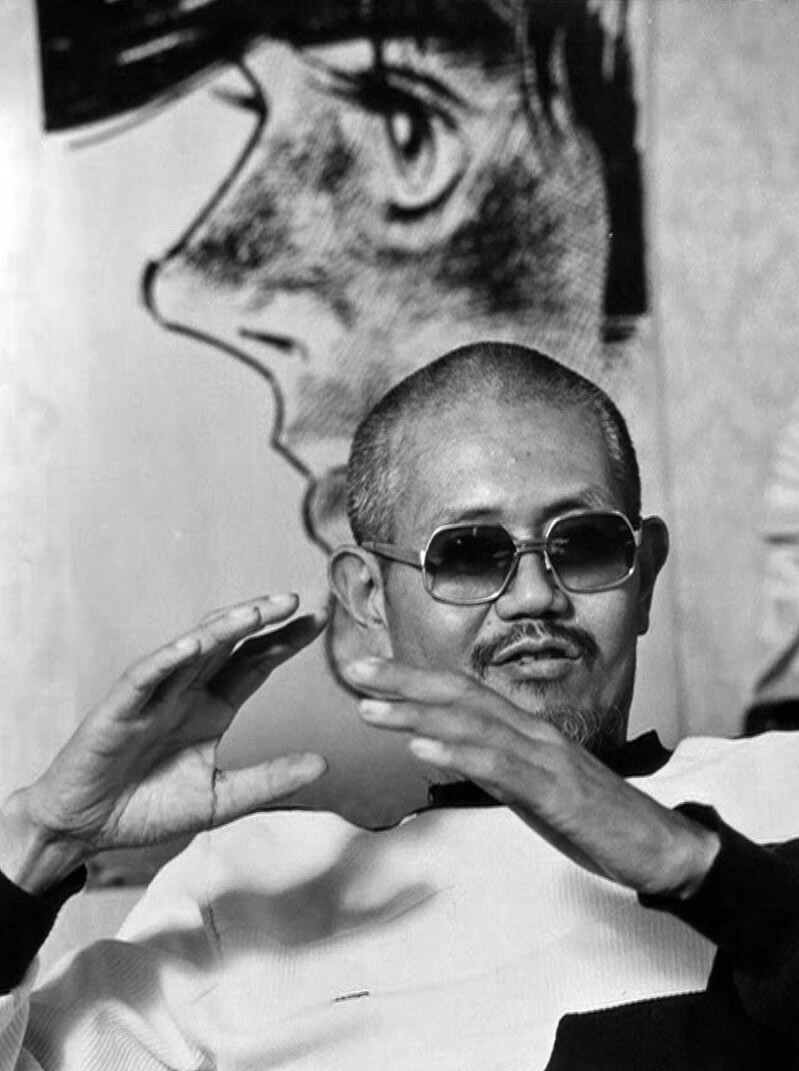

Manga author | 4 September 1936 – 21 January 1987

“A monkey that falls from a tree is still a monkey, but a politician that falls from grace via election is then just a regular person.”

Many of you may have heard these words of Ono Banboku, long-serving vice president and key figure in the formation of the Liberal Democratic Party. The point of his message is: when a member of parliament loses an election, they’re immediately out of a job.

But now in the 21st century, even the salarymen of the world can’t breathe easy.

Gone are the days when the salaryman career was considered low-risk, low-return. Even if you’re someone who works for a major corporation, you could easily wake up one morning only to find that your company has merged with some other company, or that you’re now funded by foreign capital. That kind of thing is not at all unheard of. When companies merge, it’s commonplace for them to do some restructuring to eliminate any redundancies between departments and such, and you could well be a candidate for the chopping block.

But even without any such major shifts in management, in this age of strict compliance guidelines, if you cause even the slightest problem at work you’ll be immediately put out to grass.

When you’re demoted, you might find that your subordinates who used to adore you until just yesterday have suddenly become more distant. Those same youngsters who used to always tell you, “It’s so fun to drink with you, Section Chief!,” now they’ll just leave your Messenger and LINE messages on read while they’re out happily drinking with the new section chief.

But while you might think them cold-hearted, try not to feel resentful. After all, they weren’t lying to you—they really do enjoy drinking with the section chief.

So then, how does one feel when they experience such unexpected tumbles in life? How does it change one’s attitude towards drinking and interacting with others?

Kajiwara Ikki is without question one of Japan’s most emblematic manga authors. Some of the works he brought into the world include Star of the Giants, Ashita no Joe, Tiger Mask, and Karate Master. Everyone born in the past few decades will surely have at least heard of these titles.

But the really amazing thing is that Kajiwara actually worked on all of the above around the same time frame. Star of the Giants and Ashita no Joe ran concurrently in Shonen Magazine (Star of the Giants from 1966 to ’71, Ashita no Joe from ’68 to ’73). It’s difficult to imagine in this day and age, but Kajiwara was producing two hit comics in one shonen magazine at the same time. Even after Star of the Giants ended its serialization, Ashita no Joe ran concurrently with Karate Master and Tiger Mask (which started its run in Bokura but then moved to Shonen Magazine).

His contributions to other magazines included, he was doing nearly ten concurrent weekly serializations, making him a very busy man indeed. But although he was sometimes holding a pencil in his right hand and chopsticks in his left as he wrote his manuscripts, Kajiwara was by no means someone who just stayed up working all night. And it’s not because he was conscious of his health either.

In the publication Waga Zangeroku Saraba, Geinoukai no Onnatachi!, he explains his reasoning as follows.

It’s simple: I just wanted to get work out of the way so I could go out to Ginza. I suppose the thought of spending my nights working, while admirable, was in complete odds with my personal disposition.

“Play” being the driving force behind one’s work—that part of it is understandable. But in Kajiwara’s case it was more than that. It’s like Ginza was calling for him constantly, and he was there so often he was known as the man with the “Perfect Ginza Attendance Award.”

In his biography, Kajiwara boasts that the entirety of Ginza was, in fact, his “reception room.” Apparently, when he was there he would sometimes talk about the intricacies of his work as well, but of course it couldn’t have been anything terribly complicated they were discussing, considering everyone was drinking.

Even past his 1970s heyday, the people around him would not leave a big name like Kajiwara alone. He was given a royal welcome wherever he went. Night after night, he would go on his endless pub crawls with his hangers-on that he kept around just to keep the party going, spending his nights with hundreds of different club women.

Incidentally, Kajiwara had an extremely high alcohol tolerance. Even in his forties, he would stay up all night emptying two bottles of bourbon. And even then, he never had hangovers bad enough to stop him from getting out of bed.

Unleashing himself on Ginza every night, when Kajiwara’s life took a turn for the worse, it was sudden. But then—observing his daily behavior—it was perhaps only inevitable.

On May 25, 1983, he was arrested. The direct charge was suspicion of assault, causing injury against his deputy editor from Shonen Magazine. In his book Jigoku Kara no Seikan, Kajiwara explains how the events transpired.

They were at a high-end club in Ginza, when suddenly the deputy editor cracked a joke. “Sure, you’re popular with the ladies. But you’ve gotta admit, you’re not really the best-looking guy in the world!” As we will later discuss, looks-wise, you’d have to agree that Kajiwara was not the most handsome guy ever.

But Kajiwara was drunk. And so, for this little quip, he served his deputy editor with a backfist across the table.

Kajiwara was no amateur either. He was 180 cm tall, weighed 90 kg, and was a fifth dan in karate and second dan in judo. It had to have hurt. The other party was a tough guy himself, being a second dan in kendo, but without his bamboo sword he was only a regular guy. Kajiwara’s angry blow knocked him unconscious, and according to some reports Kajiwara not only punched the man but also kicked him as well.

It’s no wonder he was arrested.

Still, this was a master author and his editor. The matter was settled on the spot, and Kajiwara figured it had been just an ordinary fight between an author and his staff. Obviously it was in no way “just an ordinary fight,” and six months later this incident would be rehashed.

In his book, Kajiwara writes that the authorities received an anonymous tip-off saying he was using stimulants. The police wanted to get him for this so badly that they made Kodansha, his publisher, file a criminal complaint about him.

Normally, the police might not act on the words of a single tattle-tale. But unfortunately for Kajiwara, he had a lot of enemies. As he began going up the ranks as a hit-making manga author, he lost all vestiges of that naive young man who had once aspired only to become a literary figure.

As is all too common, he had become arrogant.

Chiba Tetsuya, who had previously teamed up with Kajiwara to create Ashita no Joe, recalls how he was out in town one night when he happened to run into him. As Chiba tried to introduce Kajiwara to an acquaintance of his, Kajiwara curtly asked him, “Who the hell are you?”

But before even considering his personality, physically Kajiwara looked scary. I implore you to look up pictures of him on the internet. The man gave off some serious yakuza vibes.

In fact, Kajiwara was deeply connected with people from “the other side.” He was sworn brothers with Kyokushin karate master Oyama Masutatsu, and he himself worked for a long time as a Kyokushin karate advisor. They first met when 20-year-old Kajiwara heard a rumor about a man who had come back from the US who could “kill a cow with his bare hands.”

That same Oyama was good friends with Yanagawa Jiro, former don of the Yanagawa-gumi yakuza family. Kajiwara, through Oyama, became like brothers with Yanagawa as well.

Yanagawa-gumi were known as “The Yanagawa Killers.” Once, when a friend of theirs had been taken hostage, they sent just eight of their members to rescue said friend from the offices of a 100-member rival gang. They were known as one of the most violent factions under the umbrella of Yamaguchi-gumi.

No matter how arrogant he might have been, everyone knew he was close with these two killers—of both cows and men—and this made Kajiwara untouchable.

As mentioned above, he was also himself an expert in karate and judo. His father had died when he was young, and so to provide for his household he had run a bar in Kamata where he along with his brothers would frequently have to chase off the local yakuza.

Even after becoming famous he would still frequently resort to violence, including getting into a fight with a foreign wrestler and assaulting a yakuza member in the toilet after they got into an argument at a hotel bar. Not only did he have confidence in his own abilities, but he also surrounded himself with other karate tough guys to act as his bodyguards.

One time, the president of a certain company commissioned members of a violent gang to go and “punish” Kajiwara for stealing from him the mama of a certain Ginza club. But when the gang learned who Kajiwara had backing him, they refused.

Ultimately, the company president then personally marched into the mama’s apartment, demanding that she break up with Kajiwara. When the woman said no, he threw sulfuric acid at her, leading to a criminal case. When the whole story came to light, it made Kajiwara’s scariness that much more distinct.

Under these sorts of circumstances, he would naturally be intimidating to others even when it was not his intention to do so, causing many to become resentful of him. Thus, when Kajiwara was arrested for assaulting his deputy editor, he was suddenly under investigation for a number of other cases, too.

One such instance was the “Antonio Inoki Confinement Case.” These charges came about from him summoning Inoki to a hotel room where he and his friends proceeded to threaten him. Had this been your average fight, Inoki probably would’ve had the upper hand. But as they got to talking, Kajiwara’s ex-yakuza buddies could be heard calling someone on the phone, telling them to “bring a gun.”

Doesn’t matter if you’re Antonio Inoki—that’s got to be scary.

Like kicking a man when he’s down, when Kajiwara was arrested the media showered him with blows. To give an example, because Kajiwara was also involved in movie production, he would often make “acquaintances” with actresses, too. But while before his arrest the media had been forced to accept that these women were all falling for him because of his talent, the second he was arrested the weekly magazines were suddenly labeling him a rapist, saying, “No actress would ever go out with a man who looks like that. He must have raped those women.”

Part of this may have been due to the style of Kajiwara’s works prior to his arrest.

Long gone were the days of him writing stories about the simple appeal of sports. While the protagonists might’ve been karate practitioners, the women in his works would be put in confinement, stripped naked, and whipped mercilessly. Naked women tied to a raft and sent floating down the Amazon River—that kind of stuff. This level of full-on sadism must’ve been too much for the reporters, causing their imaginations to run wild.

In any case, Kajiwara had suddenly become the bad guy overnight.

While Kajiwara Ikki did leave a major mark on the history of manga, a big part of the reason why his achievements were hardly ever talked about until just recently must’ve been because of this media controversy in the final years of his life.

Yes, he was a scary-looking guy. No doubt about it. But even so, the media really did him dirty.

When he was released two months later, he naturally found that his circumstances had completely changed. At the time of his arrest, he had been working on five serializations and was making 10 million yen (USD$65,000) a month from his manuscripts alone.

What, then, do you suppose happened to all that? Waga Zangeroku Saraba, Geinoukai no Onnatachi! has the answer.

Until my arrest, my phone was ringing constantly.

Now, the calls had suddenly stopped coming. All my serializations were discontinued.

Boredom. Nothing interesting happening. I was just going out drinking every night.

While his circumstances had changed, it seems his behavior had not. You might be thinking, “You’re still gonna go out drinking?! Are you not the least bit sorry?!”

But that was apparently not quite the case.

I stopped going to Ginza. The media had beaten the crap out of me—I figured I’d be inconveniencing the establishments if I showed my face in there.

Kajiwara kept his distance from all his favorite clubs, instead hanging around night after night at hotel bars, mostly populated by foreigners. He would rotate between the Hilltop Hotel, the Okura Tokyo, and the Imperial Hotel.

But while he was still bar-hopping like he had in the past, he was now doing so for a different reason. Back when he was club-hopping, he was doing so to approach and seduce all types of different women. But now, frequenting these hotel bars, his scandal had apparently made him self-conscious about how he appeared to others, and so he could never stay in one place for long. Even someone like Kajiwara must have felt utterly defeated.

Many writings have detailed this time of his life. Judging by what he wrote in Jigoku Kara no Seikan, he was feeling rather downhearted indeed.

When I want to get drunk, I usually drink dry martinis. I’ll have about ten of those before I’m done. But drinking in Ginza, it wasn’t really so much about the booze as it was about making a racket with all the girls.

Back then, even if I went to five clubs or so, I only ended up drinking about a bottle’s worth the whole night. […] Now, drinking at bars, since most of the bartenders aren’t very talkative, I just sit there and drink in silence.

Anyone who had themselves caused an incident like this would surely turn away, reflecting alone on their loneliness. However, Kajiwara expressly writes that he wasn’t lonely. He says that “feeling lonely or sad is no different than feeling sorry for yourself,” and that the only thing he felt was the recognition that he had done something foolish.

But even while society at large now only spoke of Kajiwara in connection to assault, confinement, and rape, not everyone around him would abandon their old friend.

Kajiwara would say how people who weren’t cold by their nature would never turn their back on their friends no matter what happened. He concluded, “Some people are kind; others are cruel. The world is a complex mixture of all kinds of human emotions.”

In the spirit of self-reflection, Kajiwara also wrote the following.

I’ve come to profoundly realize the importance of multifaceted relationships, not limited to just the world of publishing. No one knows what tomorrow will bring, and so one should try and be in touch with all kinds of different people. If you cling stubbornly to only one bridge, you’re going to sink into the abyss when that bridge falls.

I see now how important it is to have normal relationships with people who have no self-interest in mind. Even if you’re busy, if you’re able to have the emotional leeway that allows you to self-sacrifice just a tiny bit and not worry about it, that will surely lead to stronger, less self-centered feelings of companionship. […] I now realize how I might have been using things like the approaching deadlines and me being busy as excuses for destroying personal relationships which I had previously held important.

This sort of advice is something one still often hears even today, but it’s an especially poignant observation considering it’s from 35 years ago when Kajiwara had himself fallen on hard times.

In early August that year, less than three months after the incident, Kajiwara was diagnosed with pancreatitis. He made a miraculous recovery, but then, on January 21, 1987, he died from heart failure at the young age of 50.

Thank you very much for this!

Hey there. Thank you for reading! Check out other chapters too if you feel like it!