Acting Debut and “The Human Condition”

After his admission into the Haiyuza Training School in 1952, Nakadai went on to rise to the top of the Japanese world of cinema in the blink of an eye.

In this chapter we trace the footsteps of young Nakadai, at the core of which is The Human Condition, the work which first brought him fame.

Movie Debut

Nakadai’s professional debut work was the 1956 Nikkatsu film Hi no Tori. He was 23 years old. Playing opposite to top actress Tsukioka Yumeji, this was a very sudden, exceptional role for him. Nikkatsu had only just restarted producing films and they were in urgent need of leading actor-level talent. As a result, they also picked up Nagato Hiroyuki and Kobayashi Akira shortly before Nakadai, and then Ishihara Yujiro right around the same time as him. At the time, they were all very much rookies who were chosen for leading roles as they quickly rose to stardom.

I was very fortunate to make my movie debut.

Haiyuza’s performance of Ghosts is what earned me my first award—they called me a “promising actor.”

Nevertheless, there just wasn’t any money to be made in shingeki theater. So to cover for our living expenses, we would work as extras in radio dramas. You know that sound of the hustle and bustle of people talking out on the street, right? The popular name for that sound effect is “gaya.”

So then this one time I was doing gaya on a radio drama featuring Tsukioka Yumeji. Recording technology back then wasn’t nearly as developed as it is today, so it would literally be Tsukioka speaking in front of the microphone with us penniless shingeki actors talking behind her, doing our gaya acting. This was right around the time of my important role in Ghosts, and yet here I was being forced to do gaya on a radio drama just to make ends meet. Anyway, as I was doing my thing behind Tsukioka, she took notice of me. “Hey, here’s someone interesting!”

Nikkatsu were in the midst of planning a film adaptation of Ito Sei’s novel Hi no Tori. Tsukioka was to play the leading part, and Inoue Umetsugu—who would later become her husband—was the director. It was a love story between a prominent actress and a rookie actor, and Tsukioka was in search of someone to play the opposing role.

I didn’t have any money to buy wigs for Haiyuza, so if I was playing a foreigner I would put peroxide in my hair to bleach it. Nowadays you’ll see people with blond hair all the time, but back then it was so embarrassing you couldn’t even walk outside with hair like that. But I had no choice, so I would go into the studio to do my radio drama job with bleached hair. Tsukioka just happened to see me like that and she found it funny. I had failed a film audition nine times, and yet I had now been noticed by Tsukioka herself—the famous actress! She just recently passed away, but she actually lived close by me for the longest time. I will never forget what she did for me that time. That’s how indebted I am to her.

I played this juvenile delinquent type—a new face in the film industry with a great ambition to find some roles quick. He was making eyes at the lead actress, gradually approaching her. On the very first day of filming we shot a love scene on the beach at Chigasaki. I was shaking—it was my first movie, it was such an important role, and I was filming a love scene with a superstar actress! Seeing my nervousness Tsukioka slapped me on the backside, telling me to “be a man.”

Tsukioka later played my mother in Karei Naru Ichizoku. Whenever we saw each other, I could only bow my head to her in gratitude.

Tsukioka Yumeji and Nakadai (with fake film crew) in “Hi no Tori”

Choosing to Go Freelance

In the 1950’s and 60’s, movie theaters would regularly see in excess of one billion visitors a year. This was commonly known as the “Golden Age of Japanese Film,” and there was fierce industry competition between the five major Japanese movie companies: Toho, Shochiku, Daiei, Toei, and Nikkatsu. Each company had their own film studios, and in those studios each company produced close to a hundred films per year. This led to the emergence of countless of superstar actors, directors, scriptwriters, as well as staff, and audiences were mesmerized by the tremendous energy produced by this simultaneous emergence of interwoven talent.

Back then, practically all movie stars would sign an exclusive contract with one of the companies, which meant that they couldn’t appear in works produced by any of the other companies. Nakadai, on the other hand, was not affiliated with any one company. As a freelancer, he was able to move from one movie company to the next.

Having done the role in Hi no Tori, I was approached by the higher-ups at Nikkatsu asking me if I would like to sign an exclusive contract with them. Being attached to them would have meant higher pay—compared to the poverty of a shingeki actor, I would have been rich indeed.

But then I just had this thought… If I became exclusive with Nikkatsu, I would have had to quit Haiyuza. But I wanted to do both theater and movies, and so I simply chose not to sign an exclusive contract with any one company. Sure, had I signed with Toho for example, I would’ve gotten the Toho star treatment and it would have meant a lot of money for me, but then I also wouldn’t have been able to appear in films by any other movie company. Ishihara Yujiro, for example, debuted around the same time as I did and he became exclusive with Nikkatsu, meaning he couldn’t appear in Toho films. Something about that just rubbed me the wrong way, and so I chose to be a freelancer—I was always moving between the five major companies. But this, of course, meant significantly less money, too.

I also wished to avoid getting into a situation where I would be constantly doing the same types of roles. Once you become exclusive with a movie company and you’re a star and you get that one big hit, you will be given the same type of role over and over again. Before I became an actor myself, I would be watching movies and thinking, “how come foreign actors can play all these different types of roles each time?” With Japanese actors, once you get that one big hit you’ll be stuck doing the same type of thing forever. I found myself unconsciously thinking how it’d just be more fun doing all kinds of different roles depending on the film.

And then there was the fact that I just loved doing theater. I chose that even if it meant that I would struggle and not have any money, I would dedicate half of each year to doing theater and the other half to doing movies. I decided that I would spend the first half of each year doing movies, flat-out stop at the end of June, and then spend the second half of the year doing theater, even if the only role I could get was that of a passerby on the street. I felt that I would do so even if I was in talks of potentially doing a lead role in a movie.

Business must have been good for the film industry back then. Even if I turned down a job because I wanted to do theater, the director would tell me they would just push it back until the following year for me. That’s the kind of era it was. I was very grateful about that.

When I was touring across the country doing theater, it would be around ten of us young guys sleeping in one eight-tatami room. But when I was out shooting a lead part for a film, I’d be sleeping in a suite on-location. I enjoyed leading this sort of a double life. And of course the pay was totally different—I mean, we did shingeki for free. “You won’t get paid for ten years or so, not until you’ve learned everything. Beginner sushi chefs work for free too, you know.” It was that sort of an apprentice system. Shingeki… It was supposed to be a new (“shin”) kind of drama, but they sure had an old-fashioned way of doing things!

I feel that all actors should also do theater. Look at Hollywood and you’ll see even big movie stars like Tom Hanks doing theater at least once every few years. Theater isn’t something you can just jump right into, not even if you’ve been film acting for decades. On the other hand, you can always make use of theater experience when doing movies.

There are some genuinely great film stars out there. But there are also many actors who were pampered by their agency or movie company from a young age, pushing a good thing too far and ruining them as actors. In that sense I really feel like leading that sort of a double life was a great experience for me.

So, having appeared in that Nikkatsu film, they asked me to sign an exclusive contract with them. “We’ll build you a house!” Going over to Toho, they’d make me the same kind of offer of exclusivity. “You could take your wife traveling around the world!” But I realized that if I let them build me a house or something, that would be like me borrowing money from them. It gave me the sense that I would be forced to do things I didn’t want to do—my life as an actor would be constrained by the whims of some movie company.

I was extremely poor in my teenage years, so of course I did have a desire for money. But at the same time, I also had a kind of distrust towards it. I first started working at the age of 11, and ever since then it had felt like everyone who’d employed me up until that point was only after money. Sure, I wanted a house of my own—I was living in an apartment. But I had the feeling that if I allowed myself to get tied down, then all that hardship I’d experienced in my teens would’ve felt like it had been for nothing. You might call it a strange kind of rashness of youth, and I suppose that’s what it was, but I couldn’t help but feel that I wanted to live a more dynamic sort of life.

From that point on, I mostly appeared in films by the request of its director. Kurosawa Akira, Kobayashi Masaki, Gosha Hideo, Okamoto Kihachi… I appeared in the films of all those different movie studios by the request of each respective director.

Say I was doing a lead role for Toho for example, by request of the director. In the beginning the executives would be saying hello, courteously giving me their greetings. But as soon as I had a flop, they wouldn’t even bother looking in my direction. They would take care of their exclusive actors, but freelance actors like me? We were disposable. Once you had another hit, however? Then they would be doing their everything to be polite again.

Meeting Kobayashi Masaki

The Human Condition was based on a best-selling novel of the same name by author Gomikawa Junpei, detailing his own military service experience; his many battles near the border of Manchuria and the Soviet Union, and later his detainment in the Soviet Union after the war. It was filmed over the span of four consecutive years and released in six parts from 1959 to ’61, two parts at a time. With a total running time of nine hours and thirty-one minutes it was the longest film ever produced at the time, being listed as so in the Guinness Book of Records. But not only was it a lengthy film, it was also the recipient of critical acclaim: it was nominated for the Golden Lion at the 21st Venice International Film Festival, and the movie received numerous awards from film critics.

This monumental work was not produced by one of the major Japanese movie companies. Instead, it was an independent production by Ninjin Club, established by actresses Kishi Keiko, Kuga Yoshiko, and Arima Ineko. The fact that even a non-major company was in a situation to be able to afford the sort of budget required to produce such a large-scale film speaks of the state of abundance in the Golden Age of Japanese Film.

Throughout all six parts of the film Nakadai Tatsuya portrayed “Kaji,” the protagonist harboring resentment towards the anti-humanist mentality of the armed forces, with an undying sense of justice. Nakadai was very much still a rookie only a few years into his career, and he had yet to appear in a single leading role. But with him attaining the starring role in The Human Condition, he instantly rose to be one of the top actors in the world of cinema.

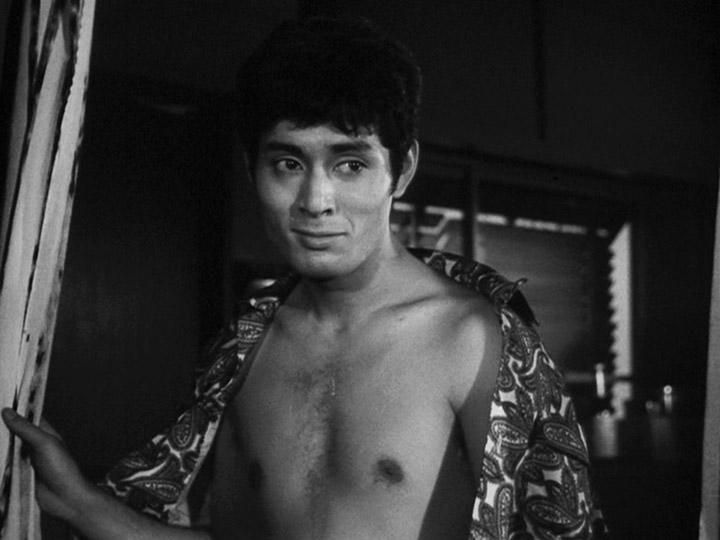

The person who selected Nakadai for the role was the director of all six parts of the film, Kobayashi Masaki—a spirited director for Shochiku, having received attention for his films like the Abe Kobo-penned The Thick-Walled Room. The first time the two worked together was on the ’57 Shochiku film Black River. In a film set against the backdrop of the rough streets near the Atsugi military base occupied by American forces, Nakadai played “Killer Joe,” the leader of an unjust gang of hoodlums.

Director Kobayashi Masaki was a quiet person. He was also in great shape—he was a single player of golf. He was a graduate of Waseda University where he was the last disciple of Aizu Yaichi who was a researcher of ancient arts. So rather than coming across as a film director, there was instead something rather scholarly about him.

He was originally an assistant director at Shochiku’s Ofuna Studios before the war. He was then called up for military service, and after he came back he became the assistant director to Kinoshita Keisuke. He had made many movies even before I met him. The one that left the biggest impression on me was the film The Thick-Walled Room which was written by Abe Kobo. I was astonished. “Oh, so even Japan has directors who make films this way!”

He was the director who first discovered me. I made my debut in the ’56 Nikkatsu film Hi no Tori, but after that I actually took part in the auditions for Kobayashi’s film Fountainhead, starring Ineko Arima. I unfortunately failed that audition, however.

But film production is a strange thing. I had left an impression on Kobayashi, and so when he started filming his next movie, Black River, he said he “absolutely wanted to use Nakadai.” In that film I was originally supposed to play the virtuous student, the role of which was actually portrayed by Watanabe Fumio. But then for some reason as our interviews for the film went on, Kobayashi came to feel that I was better suited for the role of “Killer Joe.” The villainous role of “Killer Joe” was the embodiment of a cruel, new kind of post-war yakuza. It definitely felt like a role worth doing.

Nakadai and Arima Ineko in “Black River”

However, at the time I had only just joined Haiyuza and I was set to appear in the role of a pedestrian in a Haiyuza children’s play called Rikou no Oyomesan. The two leads on it were both my juniors, Hira Mikijiro and Ichihara Etsuko. But the play was going to overlap with the filming schedule of Black River for ten days or so, and there was just no way around it. I was still only just a lowly, inexperienced rookie in the world of shingeki, and as a member of Haiyuza I felt that I just had to take part in the play. I was going to turn down Black River.

A great senior of mine, Tono Eijiro, was also set to appear in Black River. Apparently, Kobayashi had been talking to him about how he wanted to use me for the role of “Killer Joe,” but how he couldn’t because of our play. So then Tono came to see the play, and he saw how my role in it was very minor and inconsequential compared to the role in Black River which would have been huge. He spoke to Senda Koreya, the very top person of Haiyuza. “So there’s this guy, Nakadai—he only just joined Haiyuza around two years ago. Black River is a great movie and you should let him do it.” He then came and spoke to me about it. “I’ll cover for you on the Haiyuza play—you should absolutely do the movie!” So then Tono—this huge, veteran actor—did my tiny role in that children’s play for about a week. Even now I feel so very grateful to him. That film is what led to The Human Condition… The fate of an actor truly is a strange one.

Kobayashi would never say anything even if the actor didn’t act in the way he wanted. Directors like Kurosawa Akira would be on your case immediately. “Can’t you do anything properly?! Do it again!” Kobayashi, on the other hand, would remain quiet… But then he would also never roll the cameras until your acting was to his liking. In the meantime, he would offer zero explanation—you just had to give the utmost effort and focus to your acting, trying to figure out what you were doing wrong. In that sense, as a director, I might go so far as describing him as something like my foster father.

Being Chosen for “The Human Condition”

Following his appearance in Black River, Nakadai immediately started receiving many more film opportunities. He starred in the Toho hit series Oban and was blessed with the opportunity of working with master director Ichikawa Kon on the film Conflagration. However, he had not yet had one starring role—indeed, him being selected for the blockbuster The Human Condition was something completely unprecedented.

I read Gomikawa’s The Human Condition which the film was based on. I was never a soldier myself, but I was still of that whole generation of war. The themes of the work… Gomikawa’s feelings towards war; how a man who opposed the government of a country at war would change once he himself went to war… And moreover, the setting of how he was both the victim and the perpetrator… I thought it to be truly an amazing book.

When it was announced that Kobayashi Masaki would be adapting the book into a movie, it created a sensation. Who was going to play the protagonist “Kaji,” this single-mindedly righteous, heroic man? Newspapers even ran articles with actors recommending themselves for the role. Still, Kobayashi said he had not yet made a decision at the time.

In Black River, I had played “Killer Joe”—this inhumane, new type of yakuza—and so I thought there was no way I would be chosen to do “Kaji.” Still, I was hoping I would receive at least some role in the movie.

When they were in Hokkaido scouting for locations, Kobayashi was picturing in his mind the story of that entire nine-and-a-half hour, six-part movie. He later told me that, apparently, as he was imagining that final scene of “Kaji” and the look in his eyes when he has partly lost his mind… “The eyes I saw in my mind were yours, Nakadai.” When I first received the phone call from my manager, I was as shocked as anyone.

Nakadai in “The Human Condition III: A Soldier’s Prayer”

It created a huge fuss when it was announced. I was still pretty much a no-name newcomer so the distributor of the film, Shochiku, was against it. However, the film itself was an independent production of Ninjin Club, and so their president, Wakaki Shigeru, pushed back. The matter was thus settled, and they began preparations for the film. Shochiku had wanted to cast their exclusive star actor, Sada Keiji, in the role. However, Kobayashi flat-out rejected the idea and selected me instead, despite the fact that he was himself an exclusive director for Shochiku. Both Kobayashi and Wakaki hung in there, going against fierce opposition from the company.

I was also surprised by the casting of Toho actress Aratama Michiyo in the role of “Kaji’s” wife, “Michiko.” As it was Ninjin Club producing the film, the assumption was that it would be one of the three actresses in its management—Kishi Keiko, Arima Ineko, or Kuga Yoshiko—to be cast in the role of “Michiko.” But for Kobayashi it was art for art’s sake—there was to be zero compromise. I’m sure the three actresses of Ninjin Club were heartbroken.

Director Kobayashi Masaki felt driven to create this record-breaking epic production. His personal wartime experiences were something which greatly colored the film.

Kobayashi saw himself in “Kaji.” I asked him about his war experiences, and what he shared with me was indeed dreadful.

Like “Kaji,” Kobayashi himself fought in numerous battles around Manchuria and Mongolia, and at the end he was part of a unit in Miyakojima, Okinawa, meaning he didn’t have to get dragged into the suicidal final battle on the main island. Nevertheless, he was then captured and he spent some time in an internment camp as a prisoner of war—which is again the same as with “Kaji,” albeit with the difference that “Kaji” was a prisoner of Soviet Union and not America. Moreover, the director himself had always taken an anti-war stance, but in that climate of a nation at war there was nothing he could do about it. He had some real regrets about that. I believe that’s one of the reasons he was able to become so passionate about the production of The Human Condition.

And then of course the author of the original work, Gomikawa, was also “Kaji.” I actually got the opportunity of visiting him in his home a number of times, and looks-wise he was the spitting image of Kobayashi. They were both in such great physical condition. I just found myself viscerally thinking… “Huh. Kobayashi and Gomikawa are the same person.”

I simply played “Kaji” in place of those two. That’s usually the case with my movies. If I feel like I can’t quite grasp the concrete image of the role I’m doing, just watching the director will give me the gist of it. Oftentimes, the director will have an exact resemblance to the role. And so just watching Kobayashi in his day-to-day life became a great help in preparing me for my role. Even just the way he would never back down on what he said—that was the definition of “Kaji.”

Another thing that helped me in terms of preparing for the role was what I was taught at the training school: “read the book and imagine yourself in the role.” So let’s say I was reading a novel. If the protagonist in the novel was played by an actor, what sort of a facial expression would he have? What would he be wearing? How would he walk? That’s the sort of thing I’d think about. Would he speak in a high pitch, a medium pitch, or a low pitch? In the case of The Human Condition, the character of “Kaji” started his journey as this very immature man as he then went on to gradually develop, step by step. As I played him, I would think about how each of these aspects about him would transform as he grew. That’s how mindful I was as I played him.

For Stanislavski, his “Magic If” concept was at the base of his acting theory. What it means is thinking if you were to play this character, what would happen? That’s the basic premise of acting. By the same token, there’s the other type of actor such as Takakura Ken, and with him it was the movie companies who would decide to cast him in roles that made the best use of his aura and his charm. That is a wonderful thing as well, but in my own case I chose the former method—the method which allows one to play a wider variety of roles.

Growing as an Actor

The protagonist, “Kaji,” is a supervisor at a mining operation in Manchuria with Chinese prisoners as its workforce. However, “Kaji” being the idealist that he is strives to improve the working conditions of these prisoners, leading him into conflict with the on-site workers and military personnel.

In the first and second parts of the movie there is an air of immaturity about Nakadai, mirroring his role. But beginning with the third part, due to his opposition of the army’s policies, “Kaji” himself is conscripted and sent to fight in the front lines. Growing alongside his role, there can be seen a kind of toughness arising from within Nakadai as he showcases a magnificent transformation into a soldier.

The filming took four consecutive years, but as we took breaks in between to prepare for the upcoming parts, it was actually three years.

Parts one and two took six months to shoot. Then there was a period of some months for prepping, during which I appeared in Kurosawa’s Yojimbo. Then we shot parts three and four, and once that was done and there was another break, I did Sanjuro, the sequel to Yojimbo. After that, we shot the last two parts.

Rewatching those nine hours and thirty-something minutes now, I can see how even I personally changed throughout the movie.

“Kaji” is an anti-establishment, anti-war, leftist young man working at Mantetsu (South Manchuria Railway), a government company. After criticizing his management, he is demoted and sent to work at a Chinese prison camp. From the perspective of the local prisoners of war he is in effect—as a Japanese person—just one of the perpetrators, and he is troubled over how he could best treat those prisoners in a humane way. This is the kind of green young man he is when we first meet him.

He then joins the army, refines his abilities as a soldier, fights the Soviet Union, and becomes their POW… Until escaping and ultimately finding himself wandering through a desert wasteland. In doing the role, I found my own appearance becoming similarly resolute. If I may say so myself, I was shocked to see my own transformation.

There was quite a bit of training during the preparation. In fact, they had us do around a month of genuine military training for new recruits. For a whole month, we’d spend each night at the Ofuna film studios, sleeping in our pajamas, waking up to the sounds of a trumpet, and changing into our combat-ready military uniform in three minutes. I also learned things like the proper military way to stand in line and how to give orders, all through training.

There was a person on staff with military experience who coached us on everything. He took the realism so far as slapping us in the face if we were late. None of us liked that, so we all learned quick. That’s why you see us looking tougher and tougher on-screen.

This wasn’t the case with just Kobayashi, but also with Kurosawa Akira and all the other masters of every movie studio: they would all reserve lots and lots of preparation time in order to train the actors. In that sense, I actually feel bad for today’s actors—they’re just thrown straight into a combat scene or what-have-you without any training whatsoever.

In charge of the cameras on this movie was Miyajima Yoshio, who would go on to create many masterpieces with director Kobayashi Masaki. Having gone against Toho as a senior union leader during the “Toho Dispute” in the late 40’s, he then went independent and worked on films such as Imai Tadashi’s And Yet We Live. Miyajima’s highly creative camerawork and his filming style of occasionally going against the director’s wishes by his own judgement earned him the nickname of “Emperor Miyajima.”

There was another person aside from Kobayashi Masaki who was crucial to the film, and that person was cameraman Miyajima Yoshio. Truly, it felt like the film had two directors. He was fierce to the point that even if Kobayashi gave his OK on something, Miyajima might say that it was not OK. But even so, those two had excellent chemistry. They were both dancing to the same beat. They had respect for one another and they worked well together.

Miyajima himself was very much a realist. During his training as a new recruit, “Kaji” becomes a platoon leader. This means that when one of his subordinates makes a mistake, he’s the one who gets beaten the hardest. The thing that left the biggest impression on me was the scene where I was beaten up by ten guys or so. Splicing up the cuts and playing with the angles, you could make it look like I was being hit even when really I wasn’t. But Miyajima insisted that we do it in one take. There was no way for me to not get punched for real. My face was becoming all swollen and yet he just kept standing there, mercilessly rolling his camera.

It wouldn’t be an exaggeration for me to say that I learned everything I know about making movies during the filming of The Human Condition. The first thing Miyajima told me was: “You’re a stage actor. But when you’re acting in a movie, it doesn’t matter how good you are if you aren’t in the shot.”

When it’s a scene with no movement, the cameras will be set in fixed positions so you know how you will look from each angle. But when you’re acting in a scene with movement that leads to stillness, that sort of thing can be hard to grasp. For example, Miyajima might be trying to film a one-take scene like this. “You run here from over there, you stop there for a close-up, then you go over there and do your lines with Yamamura, and then you run over there, you stop and you look over your shoulder, wave your hand, and run off.”

So then when I’d run over and stop where I’m supposed to do my lines with Yamamura So—during which they’re supposed to have us in a close-up—if my center of gravity changes even slightly as I’m running I won’t be in the shot when I come to a stop. Sure, we would have markers in the correct spots during rehearsal, but they would of course be removed during actual takes. Therefore, as I was acting I would have to have almost an animal instinct in regards to things like my position relative to the camera and how it would capture me. That’s what filming was like every day for three years. It was immensely educational for me in terms of film acting.

Nakadai in “The Human Condition II: Road to Eternity”

A Diverse Cast of Co-Stars

In the first and second parts of the movie, the protagonist “Kaji” finds himself working as a labor manager at a mine in Manchuria. Upon his arrival, “Kaji”—passionate in his youthful ideals—is greeted by a number of excessively stubborn veteran chiefs, foremen, and laborers. The film’s setting mirrored Nakadai’s real life on the movie set: playing the roles of those battle-worn men were actors like Bungakuza’s Nakamura Nobuo and Miyaguchi Seiji, and actors like Mishima Masao and Ozawa Eitaro from Nakadai’s own Haiyuza—all of them mainstays in the world of shingeki. To a total beginner like Nakadai, they all seemed completely out of his reach. Similarly to his role in the movie, the difference in experience and sheer presence was evident.

I was surrounded by all these veterans who I could’ve just as well called my teachers, and the pressure was immense. The nights were tough… My seniors wanting to play mahjong with me was like a nightly ritual—and I was terrible at mahjong. But I felt like I owed it to them since they were appearing in the film, and so ultimately it would be me asking them to play. And I kept losing. I was constantly phoning home, begging them to send me more money. Pretty much my entire pay for the first two parts of the film disappeared just like that.

Well… I believe I still did well considering all the many teachers and seniors around me.

Out of all my senior actors in the film, the person I learned the most from was Yamamura So. I was young and brazen, so during one rehearsal I asked the director if I could change my line, “that’s right“—“sou desu na“ to “sou desu ne.” Yamamura quickly pulled me aside. “You need to understand that screenwriters will spend a year thinking about whether to end their sentence with a “na” or a “ne.” You are not to throw in your ad-libs at the script that they have written.” Ever since then, I have to this day never changed a single word of my lines in the scripts I have been given.

All that changed when the setting of the film moved to the battlefield. Here, Nakadai was met with many actors of his generation, such as close friends from his Haiyuza Training School days including Sato Kei and Tanaka Kunie, as well as Shochiku newcomer Kawazu Yusuke.

The director trusted me, and so he would often come to me for advice as to if I might know of someone for a specific role. There was this role of “Pvt. Shinjo.” He was a veteran, yet he would disobey his superior officers and thus he had been demoted to a new recruit. The role called for a certain cynicism, and when Kobayashi asked me if I knew of an actor who could fit the role, I recommended to him Sato Kei. The two of us had been generation-mates at the training school, and even back then I could feel a sense of cynicism about him. I thought he was the perfect fit. Sato was still back in Aizu recovering from tuberculosis, but upon phoning him I learned he was much better now so I asked if he wouldn’t mind coming to Tokyo for a bit. The director thought Sato fit the image in his head perfectly, and he was thus chosen for the role.

The director also spoke to me about the role of “a new recruit who can’t keep up with the training, so he commits suicide in the bathroom.” He asked me if I knew of someone suitable, and I recommended Tanaka Kunie. He was three generations my junior, and at the time he was still almost entirely unknown.

Compared to parts one and two, I was now living together with all these actors I was close with who were the same age as me. It felt like we were all comrades. We’d have fun every night, drinking cheap liquor at our on-location lodging house. There was this card game called dobon that was all the rage back then, so we would be constantly playing that while drinking. We knew there would be an intense day of filming waiting for us in the daytime, and so at night… We would drink.

It’s incredible how we were even able to do that type of filming while having had drinks the previous night. Near the end of part four, there’s this scene where I’m surrounded by Chinese soldiers, there are machine gun bullets whizzing past me, I’m crawling along trying to escape, running through the gaps of all the shells exploding around me one after the other… I’m amazed I could even move like that while hungover!

Kobayashi’s Demanding Direction

All six parts of the movie were set in Manchuria and Mongolia. Almost as if filmed at the actual scenes of war, the locations featured in the story show lands stretching far beyond the horizon. But because there were no diplomatic relations between Japan and China at the time, the film was shot entirely in Japan.

Kobayashi and Miyajima had both seen Manchuria first-hand, so when they were doing location scouting they struggled to find the sorts of vast areas of wilderness which one might’ve seen in Manchuria. It had to be total wilderness with no light poles or anything else. Ultimately, they found these wetlands out in Sarobetsu Plain nearby Cape Soya. We filmed quite a bit there. In addition, we went all around Hokkaido. Most of the cast only shot in one or two locations and they’d be done, but I had to go everywhere. It was like we were in a traveling caravan, me and the staff. Sometimes we’d stay in guesthouses, but there were so many staff members and actors that we couldn’t all fit in one place. Hokkaido still had lots of coal mines in places like Bibai back then, so we’d rent out guesthouses in those sorts of spots.

Kobayashi and Miyajima both said that the biggest difference between Japan and Manchuria was the clouds. For instance, there is a scene during the first part when a train carrying extras playing Chinese prisoners stops in the middle of the wilderness. The prisoners, completely starved, collapse one after the other as they get off the train.

On the day we were supposed to film that scene, it was perfect weather and the sun was just lovely. We all thought we would get to shoot it that day when suddenly they told us it was a no-go. When asked why, Kobayashi and Miyajima just said, “those aren’t the clouds of Manchuria.” We then proceeded to wait an entire week for those “Manchuria clouds.” And eventually, they did show up—those huge, fluffy clouds that do seem to be quite rare in Japan. It was only when we had the clouds that we could finally begin shooting.

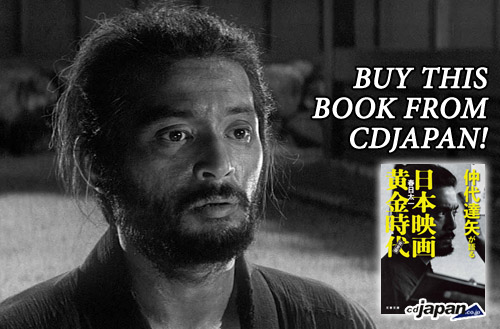

On the set of “The Human Condition”

(L-R) Aratama Michiyo, Nakadai Tatsuya,

Director Kobayashi Masaki, Cameraman Miyajima Yoshio

Beginning with the third part, some highlights of the film are surely the various extremely realistic combat scenes that depict those miserable battlefields. Exchanging blows while drowning in a swamp, running through trenches with bombs and bullets flying past, carrying all their equipment as they walk through slushy wetlands… Even just watching those scenes on the screen, one can grasp in a very real way the harshness of these situations of the time.

Later on, I came to call Kobayashi by the name of “Kobayashi the Demon.” That’s how relentless the filming was. Me and Kobayashi were the only two people who didn’t get sick even once during those four years. Everyone else, they all got sick. And it’s no wonder—we had to do things like hiding under passing tanks and falling into frozen lakes at sub-zero temperatures. And yet, most of it didn’t bother me much.

I feel like the job of a professional actor entails satisfying any and every one of the director’s demands.

The thing about actors is, as long as we think that whatever we’re doing will be captured by the camera, we can do anything. We could be at a wetlands site somewhere, splashing around in a bottomless swamp, and while it isn’t pleasant we can do it no matter how hard it is because we’re thinking, “this will be captured by the cameras and it will have impact.” We sincerely wish for it to be the best film that it can be.

There was that scene where I had to run and crawl under a moving tank. One mistake and I would have been crushed to death. When the director told me to prepare myself for it, I admit… I had no appetite for a week leading up to the shoot.

When I told this story to Mifune Toshiro, he told me about how he’d had real arrows shot at him in Throne of Blood. He said, “No matter how professional they might be, if I made one small mistake as to my position, I was dead. I couldn’t eat for a whole week because of it.” But then just before the real thing you think to yourself, “there’s no helping it—I’ve just gotta do it.”

At the end of the sixth part of the film, before we shot the scene where “Kaji” escapes from a Siberian POW camp and is then wandering aimlessly in the wilderness, Kobayashi barely let me eat anything. (He did allow me to drink alcohol, though.) “Please don’t eat. You have to lose around six kilos or so in the next week.” But then he also didn’t allow me to even sleep! “I’m not going to sleep either—I’ll do this with you,” he said. Well, I do believe he did eat though… In any case, it didn’t take long for me to lose those six kilos.

The sixth part concludes the film. “Kaji” is detained by the Soviet Union and sent off to a prison camp in Siberia, but he manages to escape. Wandering endlessly through the Siberian wilderness without aim, he finally collapses. In the closing scene the falling snow continues to pile on top of “Kaji” until finally, when his form can no longer be seen, the film ends, leaving the viewer with an immense feeling of utter desolation.

“Kaji collapsed. The falling snow kept piling on top of him until it had formed a small hill.” That is how the original work ends, and Kobayashi intended to film that scene exactly as-is. We filmed it right there in midwinter Sarobetsu Plain, in a location with heavy snowfall.

There was absolutely nothing there. Before the shoot, we stayed in this rest area they’d built that was enclosed with veneer, and they had these Gangan oil cans that each had five or so charcoal pieces in them to keep us warm. We waited there until the snow was just right, and then I was told to go. I fell down to the ground, wearing just my thin coat costume. They intended to keep filming me all in one take until an actual hill of snow had formed on top of me.

They kept filming until every part of me had become covered in snow. It was ten-something degrees celsius below zero—a place cold enough where one usually wouldn’t even be able to stand still, and I was going to just keep lying there until I was completely covered in snow. Little by little my hands and feet began to go numb, and near the end… it started to feel strangely pleasant. I thought to myself, “this must be what freezing to death feels like.”

All this time, I could hear the sound of the cameras still rolling. This told me that if I got up, the take would be ruined and my perseverance until that point would have all been for nothing, so I simply kept desperately enduring it. And then, just as it began to feel good and I was about to lose consciousness, I heard “cut!”

The AD’s immediately rushed out to me all at once. First, they took that ragged outfit off of me and stripped me completely naked. But if they’d taken me directly into that veneered room with the Gangan cans, I would have been at risk of frostbite. So first I had five or six AD’s just slapping me all over my body—that would heat up my skin so I could finally go in and warm myself by the fire.

So as I was standing there being slapped, I thought, “Wait, where’s the director? And where’s Miyajima?” They were both gone. Once I got to warm myself up by the fire and I could catch my breath and change into my own clothes, I remember thinking to myself, “Huh… They made me go through something so extreme and yet the director and the cameraman are both gone.”

I found both men waiting for me in the car. I got into the passenger seat, the two of them were sitting in the back… And yet, they offered me not a single word of gratitude or appreciation. They both just remained silent.

Even once we were done with all six parts of the film, I barely heard a word from Kobayashi. Director Kurosawa Akira would always congratulate me afterwards and ask me if I was okay—the two of us always worked together on all these relentless, pandemonic scenes as well. But with Kobayashi, he always just kept quiet. Just to be clear, this was by no means because he lacked compassion or some such. It was just that he saw all of that as simply being par for the course in our line of work.

In any case, I devoted four years of my twenties to work on The Human Condition, and thus I think of it as my youth. And what a hell of a youth it was.