Nagabuchi Yozo

If you made it to work but you’re hungover

Baseball player | 4 May 1942 –

Whenever someone asks me why I drink, it always makes me flinch.

“Because it feels good,” I answer them. But if you picture a man who’s drunk himself to an unconscious state, breathing heavily with an anguished look on his face, while the man himself might be feeling good it sure is a pretty repulsive sight to anyone else.

Sure, it’d be all good if you could just stop right before you reach that “dead drunk” stage. But unfortunately, it’s difficult to recognize when you’re about to cross that line you’re not supposed to cross.

Here’s something that someone told me right around the time I first entered the workforce. “Even if you get hammered when you’re young, you’ll get the hang of it eventually. You’ll gradually learn to drink more responsibly. So drink away and don’t worry about it.”

So I took their word for it. I’ve simply kept drinking, “not worrying about it” while devotedly and haphazardly continuing to drink myself to states of drunken stupor, and pretty soon I will be past the age of forty.

But the thing is that even when you do drink yourself to oblivion, morning still comes.

Doesn’t matter if there’s a huge typhoon, if it’s the heaviest snowfall in decades, or if it’s the end times and there’s literally spears raining down from the sky—the Japanese salaryman is nevertheless expected to keep marching towards the office. Even if he’s hungover and his futon is absolutely covered in filth, he simply has to carry his body to work.

But suppose he does. How exactly is he then going to be able to do his job in his debilitated, near-death state? Is there truly even a need for him to be at work in the first place?

While many people end up spending days like that as if they were a disabled person, Nagabuchi Yozo—model for the protagonist of popular baseball manga Abu-san—would always show up on the field even in times when he had been busy drowning himself in booze the night before.

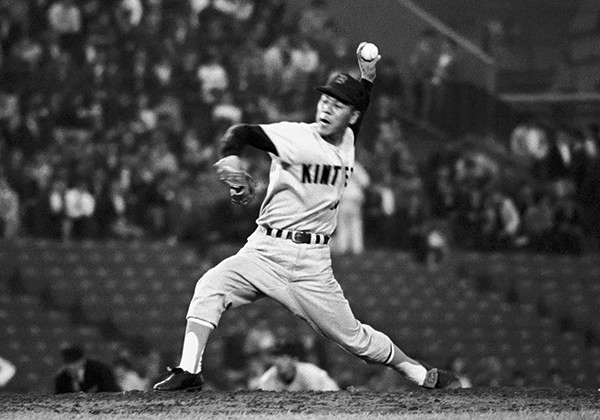

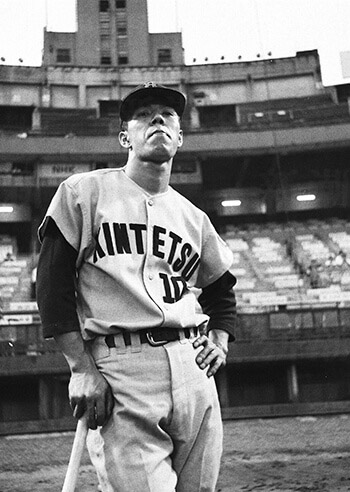

Through the prestigious corporate baseball team of Toshiba, Nagabuchi went on to join the professional baseball team Kintetsu in 1968. He made headlines as a “two-way player,” someone who would play both as an outfielder as well as a pitcher. In his his second year, he devoted himself to being a batter and acquired the title of top hitter.

(By the way, while in more recent years major league athlete Ohtani Shohei is also a two-way player, the original two-way playing pioneer was Noguchi Jiro. For six seasons, Noguchi exceeded wartime and post-war averages for pitching and batting, ranking among the top ten players in two of those seasons. Rivaling some of the representative pre-war righties like Sawamura Eiji and Victor Starffin, he had a total of 237 wins and 830 safe hits. In 2016, when Ohtani reached a double-digit number of wins and over 100 safe hits, it was the first time in 67 years for this to happen in Japan after Noguchi had accomplished the same in 1949.)

But let us get back to Nagabuchi. While he had started showcasing his talents as a professional batter, when it comes to the main subject at hand—alcohol—he was actually not a big fan until his twenties.

In an interview with Asahi Shimbun on January 19, 2004, he answered as follows.

I took the test for Nishitetsu when I was 23, but due to my small size they couldn’t even be bothered to properly assess my playing, and I was rejected. Going pro was the only thing I’d wanted in life, so I was in shock.

That’s what started it. I began going out drinking pretty much every night.

He started drinking to drown his sorrows, and before he’d noticed it his tab at the bar had ballooned to 300,000 yen. Considering how Nagabuchi’s monthly salary at the time was only 30,000 yen, he was really hitting that bottle hard.

And the surprising thing about it is that it’s not that Nagabuchi had started going to some high-end clubs either. He had accrued this debt—ten times the amount of his salary—at your average izakaya bar that serves fried tofu for 180 yen.

Nagabuchi—who was working at Toshiba’s accounting department at the time—pondered what to do. How was he going to repay this debt? If he was to set money aside and try paying it back little by little, he didn’t even know how many years that would take him.

He decided that he would simply have to go pro and use the resulting hiring bonus to pay them back.

It was a crazy idea. But then if one is incapable of dreaming big, that might mean they’re not suited for the professional world to begin with.

Although he was small in stature, he did have the chops. And so, through a high school connection of his, he was the second draft pick by Kintetsu who had a shortage of left-handed pitchers. Just like he’d planned, he was able to repay his debt, and his salary tripled. And so, without delay, he went straight back to drinking every night.

A life of no regrets and no savings, one might call it.

Looking back, Nagabuchi says that as soon as he’d repaid his debts, he was in a mental state where he wouldn’t have cared even if they’d fired him right away.

But life works in mysterious ways. While he had initially joined the team as a pitcher, after celebrated baseball manager Osamu Mihara witnessed Nagabuchi’s batting, he went on to devote himself to just that, quickly making him very successful as described above.

Rain or shine, Nagabuchi would drink.

No matter how good or bad he was feeling, he was always going out drinking. The optimal dose for him was a one-sho (1.8 liter) bottle of sake, or 20 bottles of beer when that was what he was having. But despite his hangovers the next day, he would still head out to the batter’s box without fail, and strangely enough his nausea would always fade away when it came time to demonstrate his masterful batting.

At the third All-Star game in 1969, he had been drinking all night long the previous evening, not getting a wink of sleep. He arrived at the stadium, but seeing as there was still time to spare, he headed out to drink beer at a nearby cafe.

And yet, he gave an MVP-like performance at the game, scoring a home run off Horiuchi Tsuneo (Giants) in his first at-bat and getting hits from Takahashi Kazumi (Giants) and Kaneda Masaichi (Giants). (The game was a tie; no MVP was awarded.)

But even Nagabuchi made the occasional blunder, as detailed in the book Sengo Pro Yakyuu 50nen — Kawakami, ON, Soshite Ichiro e.

The president of a certain construction company was taken with Nagabuchi’s talent for drinking, and so whenever Nagabuchi was in Osaka—Kintetsu’s home base—he would invite him out for drinks every night. He would start drinking from around 10:30 P.M. and get home at around 3:00 A.M. To mix things up, he would rotate between a one-sho bottle of sake and a bottle of whisky.

If you keep drinking like that every night when you have a game the next day, it doesn’t matter even if you’re a professional baseball player who’s in great shape—there’s going to be times when you don’t feel so hot.

So what do you do when that happens?

Well, as it turns out, both the professional baseball player and the salaryman act very much alike when they feel sick.

I was at the right fielding position, and as I was stooping down I began to feel nauseous. Finding the exact moment between pitches, I vomited out the contents of my stomach right there onto the field.

Because he was playing defense he couldn’t just rush out to the toilet. Thus, his only option was to throw up on the spot. Naturally, you’d expect people in the stadium to make a fuss. But there is an unexpected twist to the story.

Not one person noticed. There were only 2000 people in the audience that day, so I guess it’s no surprise. And especially at the right outfield bleachers, there were only around a hundred people in those seats, so there was no way they’d notice.

At the time, there was a major disparity in popularity between the Pacific League (home to Kintetsu) and the Central League (home to teams like Giants and Hanshin). Pacific League matches were often deserted, and spectators were commonly more interested in their yakiniku or nagashi somen noodles rather than the game, so it’s little wonder that no one would spot Nagabuchi barfing on the field. You do feel bad for the players though.

The only person to notice Nagabuchi’s anguished expression was right-field umpire Tagawa Yutaka (who later became Pacific League’s umpire-in-chief). He then approached Nagabuchi to have a word with him. “I’m a drinker myself so I’m not really one to talk, but you really ought to stop drinking so much that you’re throwing up the next day. You’ve got some real talent, boy. Be sure to cherish it.”

Upon being admonished in this way, Nagabuchi nearly burst into tears.

But while he was deeply moved by Tagawa’s concern, he had of course not learned his lesson. He went out drinking that very same night.

As he entered the establishment’s toilet, there was an older man there who was puking. Rubbing the man’s back, he thought to himself, “Sheesh, this old guy…” When the man finished vomiting, he turned around. And wouldn’t you know it, it was Tagawa himself.

It’s your quintessential story of how drunks can be kind to others, but even kinder to themselves.

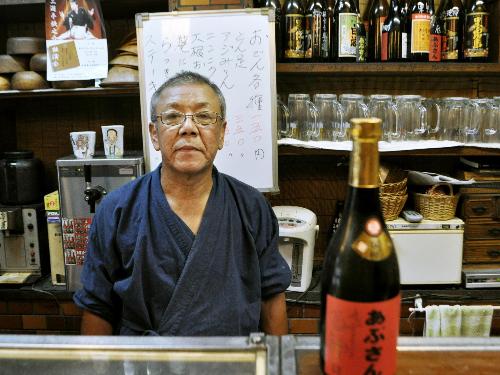

Nagabuchi Yozo at his izakaya bar “Abu-san”

Nagabuchi was very much a pragmatist.

Because he was so small in stature, he would refrain from practicing to save his strength, and right after he was done with his pinch-hitting he would be dismissed and he’d go take a bath. Sometimes his batting turn would come around during the same inning, and he would have to hurry back out to the batter’s box still smelling of soap.

In his second year with the team—practically right after he’d joined—as they were finishing up with their training at the camp, there was still some time left until dinner. And so, not caring the least bit about what the others might think, he produced a one-sho bottle of sake and began drinking its contents out of a teacup.

Seeing that this was very much a man who went his own way, his teammates around this time started referring to Nagabuchi as “Boss.” Thus, even when he did throw up on the field and everyone saw it, they all probably just thought, “That’s typical Nagabuchi for you.”

Office workers are similarly allowed to look tired at the office when they have a hangover. And while tossing one’s cookies all over your desk is probably not okay, you can at least just hole up in the office toilet when you need to.

It’s tough being an office worker in this day and age. “Stop slacking off!” “We must increase productivity!” You hear this stuff so much it makes you sick.

However, even if you’re constantly “on the job,” standing up straight from sunrise to sunset, it doesn’t make any difference if you can’t actually get the job done. And so, even if you are hungover and you feel rotten, be the pragmatist who gets the results. It’s this “Nagabuchi Model” of doing things that we should all be striving for in this current era.

In 1980, a year after Nagabuchi retired, he began running Abu-san, a yakitori restaurant in his hometown of Saga. He managed the restaurant together with his wife, but due to health issues they closed shop in October 2018.

During their years of operation, baseball fans from all over the country would come over to see this man in action, roasting his chicken skewers, always with a drink in hand just as he’d learned to do in his days as a boozehound athlete.