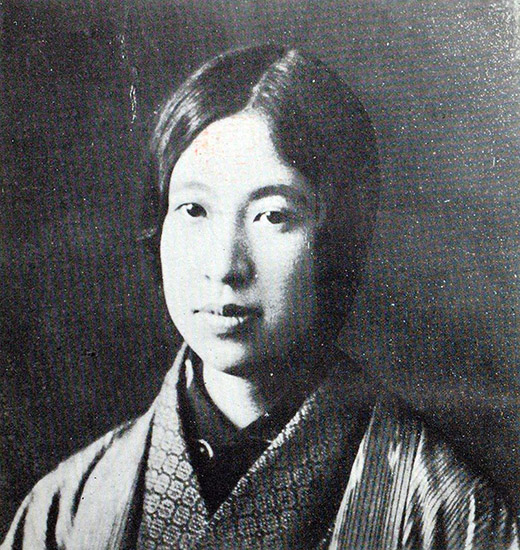

Hiratsuka Raicho

If your coworker hurls rocks at your house and still you don’t stop drinking

Thinker | 10 February 1886 – 24 May 1971

The proportion of women over 40 who regularly consume alcohol is increasing.

According to a survey by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, the percentage of women in their forties who drink frequently (meaning more than one unit of alcohol on three or more days a week) has seen a drastic rise in the last 20 years. It now stands at 15.6%—an increase of 5.7% since 1996. On the other hand, the percentage of men in their twenties who drink has dropped to less than a third of what it used to be, falling from 36.2% to just 10.9%.

Surely a result of women’s social advancement and diversification of interests, if you actually go to a bar and do a quick visual survey, you will instantly notice the multitude of lively women present there. Then, almost as if to prove the results of this survey correct, if you go and read the comments on forums discussing this news, you will find numerous young men saying things like, “Alcohol just tastes bad.”

But while it is none of anyone’s business what anyone else drinks or does not drink, you still come across comments saying things like, “What are you aunties doing, drinking alcohol? And you call yourselves women?” Apparently, it does bother some people.

“I can’t make it through life without alcohol.” Surely this is a sentiment shared by both men and women alike. But with criticism like the above still being directed at women today—in the 21st century—it isn’t difficult to imagine what women of ages past had to go through if they happened to be someone who liked to get under the influence.

They would get called “sluts,” and people would stone their houses. “Stoning? That’s beyond barbaric!” One might be inclined to think so, yes, but that was simply the reality of life in Japan around a hundred years ago.

And one person from back then who almost got killed—for the simple reason that she enjoyed getting sozzled—was Hiratsuka Raicho.

Bluestocking Magazine, first published in September 1911 with Raicho playing a central role, was known for its manifesto: “In the Beginning, Woman Was the Sun.” But although some people might think this is what made her famous, Raicho was actually a well-known “troublemaker” even before the magazine.

Born as the daughter of a bureaucrat, after attending the girls’ high school affiliated with Tokyo Women’s Higher Normal School (now: the Junior and Senior High School affiliated with Ochanomizu Women’s University), Raicho then went to Japan Women’s University.

At a time when it was expected for women to marry immediately after graduation, Raicho instead devoted herself to practice of Zen Buddhism, walking around downtown wearing her hakama. This already makes her a bit unusual. And maybe not just “a bit”—she was also sexually uninhibited while doing so, saying that she was personally taking the initiative in going around seducing monks. (Perhaps it’s best not to expect people who have left their mark on history to be big followers of standard social etiquette…)

Raicho first garnered public attention with her “Attempted Double Suicide Incident.”

In 1908, at the age of 22, she had a failed suicide attempt at a hot spring resort in Nasushiobara together with Morita Sohei, a pupil of Natsume Soseki. They made a big fuss about it in the newspapers, and Raicho found herself amidst a huge scandal, showered in criticism.

Incidentally, the other party, Morita, was a bad drunk. He, too, was attacked by the public after this failed suicide attempt, and he sought refuge at Soseki’s place. While Soseki agreed to protect Morita from this scandal, he also instructed his wife not to serve him any alcohol as he was “not a guest.”

The wife, however, felt bad for Morita, who was just keeping himself hidden in the female servants’ bedroom out of shame. She would bring him alcohol when Soseki wasn’t at home.

Morita, embarrassed by the whole situation, would initially just sip little by little. But as time went on, he gradually became more and more brazen until finally he didn’t care even if Soseki was home trying to get some sleep.

Noisily walking around the house, he would go into Soseki’s library to get some books while loudly proclaiming in the corridors how the wife had served him alcohol that day. He was your archetypal lousy drunk. Meanwhile, Soseki would be complaining about it to his poor wife. “You let the guy drink again, didn’t you?!”

Even aside from this failed suicide incident, Morita was always causing trouble for Soseki. He would do things like bring other drunks to his home, infuriating Soseki. In the year following the attempted double suicide, Morita debuted in Asahi Shimbun with the serialization of Baien, his novel based on the incident. His trouble-making knew no limits.

Furthermore, even though he had up until this point received so much help from the man, Morita would actually disparage Soseki in public. He would say things like, “His novels are not really novels in the true sense of the word.” Or—because his wife was the only woman Soseki knew—Morita said, “All the women in his stories are made-up. None of them are alive.”

Both ungrateful and audacious, this guy.

In 1920, after Soseki’s passing, Morita became a professor at Hosei University through a connection with another Soseki pupil, Nogami Toyoichiro. The two then got into a conflict, however, and Morita left the university.

In all honesty, this man is more known for the scandals in his personal life rather than his written works. And the biggest of those scandals, as all would surely agree, was his attempted double suicide with Raicho.

For Raicho, this incident gave her some first-hand insight into the social structures in which women are oppressed and into the reality of male chauvinism, leading her to start thinking about self-liberation. And so, using the wedding money her parents had prepared for her, she launched the publication of Bluestocking.

…Or so I write, but the above is no more than your average textbook interpretation. Given Raicho’s wildly unpredictable behavior, it’s impossible to say whether any of that is true or not. Who knows, she may have just been thinking, “Oh, great. Now my suicide partner’s saying he never had any intention of marrying me to begin with, and suddenly everyone’s treating me like I’m some sort of a scandalous woman. I might as well start up a magazine or something. It’s not like I have anything better to do.” It certainly feels like the majority of all new businesses are started in a similarly casual manner.

Perhaps helped in part by the general feeling of hopelessness immediately in the aftermath of the High Treason Incident which had led to the execution of Kotoku Shusui and others, the magazine’s first issue of 1,000 copies sold out immediately.

The magazine’s message for women to be “more free” resonated with their audience, and the Japanese Bluestocking Society was soon receiving an endless stream of passionate letters and subscriptions. People like poet Yosano Akiko and critic Ikuta Choko were giving them high praise, and at the height of its popularity the magazine was selling 3,000 copies a month.

Naturally, not everyone was a fan of what Raicho and the Bluestocking Society were doing. As they were advocating for women’s individuality and self-liberation—ideas which ran contrary to the existing traditional family system—the majority of men did not look kindly upon them.

When you put it like that, men in their conservatism sure do come across as utterly hopeless no matter what the era. Men can be terrible, no doubt about it.

But Raicho’s behavior, too, could be pretty erratic.

Trailblazers are always going to be radical. Her motto being “I will do everything that men do,” Raicho would systematically imitate men’s behavior. She smoked and drank, of course, but in addition she would also wear a cape as well as gold teeth. She must’ve come across as someone pretty suspicious. (And even back in those days, I get the feeling that men who looked like that were but a small minority.) But then Raicho couldn’t have cared less about potentially looking suspicious.

And it wasn’t just her. Other members of the Bluestocking Society were causing uproar in society, too.

When one of its employees, Otake Kokichi, went out to a bar to hand out advertisements, she happened to drink a layered, multi-colored cocktail consisting of five Western liquors of different relative densities. Her doing so became a huge deal in the newspapers, and they were quick to name this the “Five-Colored Alcohol Incident.”

Now, when you think about it—although it’s hardly rocket science—the only thing that happened here was that a woman drank a cocktail at a bar. And this, they said, was an “incident.”

Furthermore, when Raicho along with Kokichi and others went to a red-light district and spoke with the prostitutes there, they wrote this up in the papers as “GIRLS LIVING IT UP IN YOSHIWARA!” Sure, even in the present day it would come across as somewhat odd for women to be going to a hostess bar by themselves, but it’s hardly something to make a huge fuss about.

What with these scandals, the headwinds against Bluestocking were growing stronger.

Girls’ schools banned buying and reading of the magazine, people were throwing rocks at Raicho’s house around the clock, and Bluestocking Society was constantly receiving threatening letters. Very extreme.

Raicho now stood in fear of her life. And when you think about why this was the case—although, again, it’s hardly rocket science—her only “crime” was going out drinking and speaking to prostitutes. Even so, she would not budge. She kept writing about things like prostitution and abortion, themes which were considered to be very radical at the time.

Encouraged by their own radicalism, many of Bluestocking Society’s members also began leaning towards homosexuality.

Raicho herself started dating Otake Kokichi. But even while Kokichi was still infatuated with her, Raicho began living together with Okumura Hiroshi, a destitute painter who was her junior. (By the way, the term “wakai tsubame” (“boy toys”)—used to describe young men who become lovers to older women—actually first originated from Raicho and Okumura’s relationship.)

Raicho, now becoming busy with her love life (while also having a bit of that disposition of a princess not very suited to office work to begin with) began rapidly losing interest in the magazine.

It was under this set of circumstances when Ito Noe—who would later become the partner of anarchist Osugi Sakae—entered the picture.

Noe got Raicho to relinquish her seat as the editor-in-chief, telling her, “If you’re not even going to do it properly, then let me do it.” Noe took over the magazine in 1915, setting out to “break down all customs,” and the content became even more radical than in Raicho’s time. But ironically, Noe would end up going down the same road as Raicho: she became completely absorbed in her relationship with Osugi Sakae, and no longer had time to attend to the magazine. Finally, in 1916, Bluestocking was forced to cease publication.

Something of great interest, though, was this relationship between Raicho and Noe.

Raicho was not a fan of housework. And so one day, Noe told her that if she paid for all the materials, she would take care of all the kitchen work for her. Raicho then specifically moved to a location closer to Noe, and they formed an agreement that every day Noe would make her lunch and dinner for ten yen a month.

However, when Raicho actually went over to Noe’s house, she was surprised to find that there were no cooking utensils to be found anywhere. Regardless, Noe insisted that she was going to treat her to a meal. Raicho was curious to see how exactly she was going to manage that.

Noe, kitchen knife in hand, turned her mirror upside down and began using it as a substitute for a chopping board. Not even Raicho could hide her astonishment. Sure, she may have been unconventional herself, but you can imagine how she might have been taken aback by Noe’s sheer brashness.

Raicho would subsequently write that Noe was “honest, pure, and innocent,” but also “arrogant, selfish, stubborn, self-serving, irresponsible, audacious, and detestable.” Reading all that, one gets the sense that she might have been a tiny bit annoyed with this woman. But hey, she was, after all, paying her for her services.

Dadaist Tsuji Jun—who had lived with Noe even prior to Osugi—described her as “obstinate, a crybaby, brooding, jealous, slovenly, lacking in economic sense, and uncouth,” but also as “a genius.”

Raicho and Noe, these two intense personalities whose paths crossed in Bluestocking, would subsequently end up going down two very different paths in life.

In 1923, after the Great Kanto Earthquake, Noe—who had been drawn into Osugi’s political activities—was murdered by the authorities along with Osugi.

Raicho, on the other hand, after giving birth to Okumura’s child, became focused on implementing a system that would allow for the coexistence of both motherhood and work life. In the Taisho era (1912–1926), she along with Ichikawa Fusae established the New Women’s Association, and then in the Showa era (1926–1989), she started up a consumers’ co-operative.

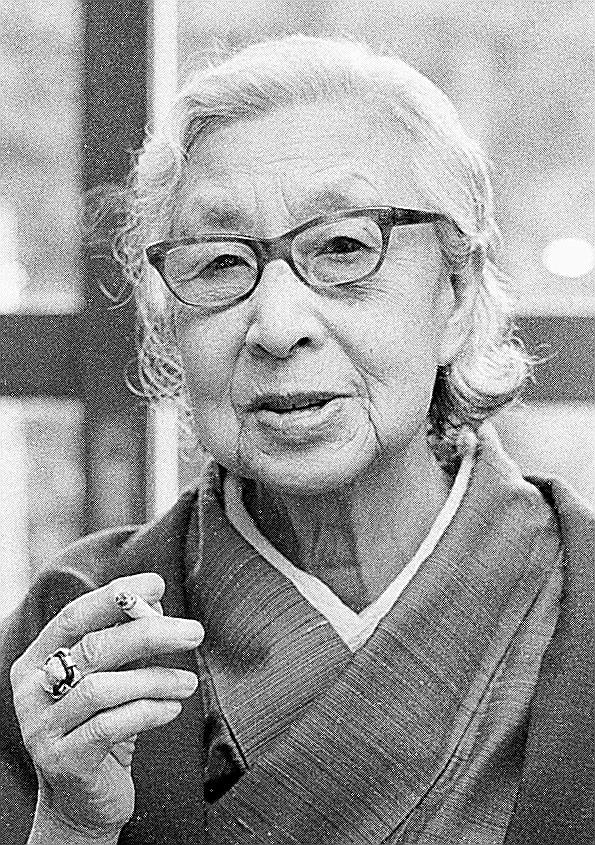

In her later years, she was a completely different person from her younger self, leading a very peaceful life. She had a fondness for alcohol, and would often tell her adult grandchildren to come and join her for a drink.

Raicho passed away in 1971 at the age of 85.

If you go on beer manufacturer Kirin’s website, they’ve put together a column about the history of beer entitled “Modern Japanese People Who Loved Beer.”

In it, the person introduced as “women’s liberationist who enjoyed beer when on break from magazine production” is none other than Raicho. It describes how she would regularly drop by at beer halls or bars after work or meetings, and when she threw her New Year’s parties, the lavish food at those fancy restaurants would always be served alongside rows of beer.

While all of that is completely ordinary in the present day, even just the manner in which she is introduced there should give you an idea as to how unusual it used to be for a woman to be going out for a drink.

By the way, while the aforementioned column introduces 30 people—including Fukuzawa Yukichi, Mori Ogai, Nishi Amane, Takahashi Korekiyo, and Ishikawa Takuboku—the only woman featured on it is Hiratsuka Raicho.