Kajii Motojiro

If your coworker throws a tantrum and lies down in the middle of the street

Author | 17 February 1901 – 24 March 1932

When one hears the name “Kajii Motojiro,” the first thing they think of is lemons. When one hears the word “lemons,” the first thing they think of is Kajii Motojiro.

Okay, that might be an overstatement. The first thing they think of is lemon soda. And lemon sours. But right after those two things, it’s Kajii Motojiro. Even before one thinks of lemonade, they would think of Kajii Motojiro.

Even if you have never read his works before, surely many among you would at least be reminded of the title of Lemon upon the mention of his name.

Kajii died of tuberculosis in 1932. He was 31 years old. Because he died so young, he left behind only around 20 short stories. The majority of these stories were released in fanzines, and only one book of his writings was published during his lifetime.

But although he died in near obscurity, people such as Kobayashi Hideo began giving him high praise just before his passing, and he would go on to influence a great number of writers after his death. Having had many supporters both pre- and post-war, there have now been over a thousand literary criticisms and essays written about Kajii.

Lemon is a mere 13-page short story. Just to give you a brief plot outline, it’s about a protagonist whose heart is burdened with “an inexplicable, ominous lump,” and he ends up at Maruzen Department Store with a lemon in hand. He then places the lemon—likening it to a bomb—on top of a stack of books, and he simply walks away.

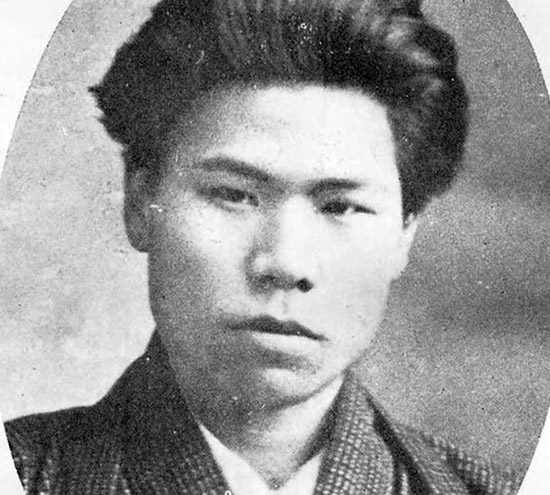

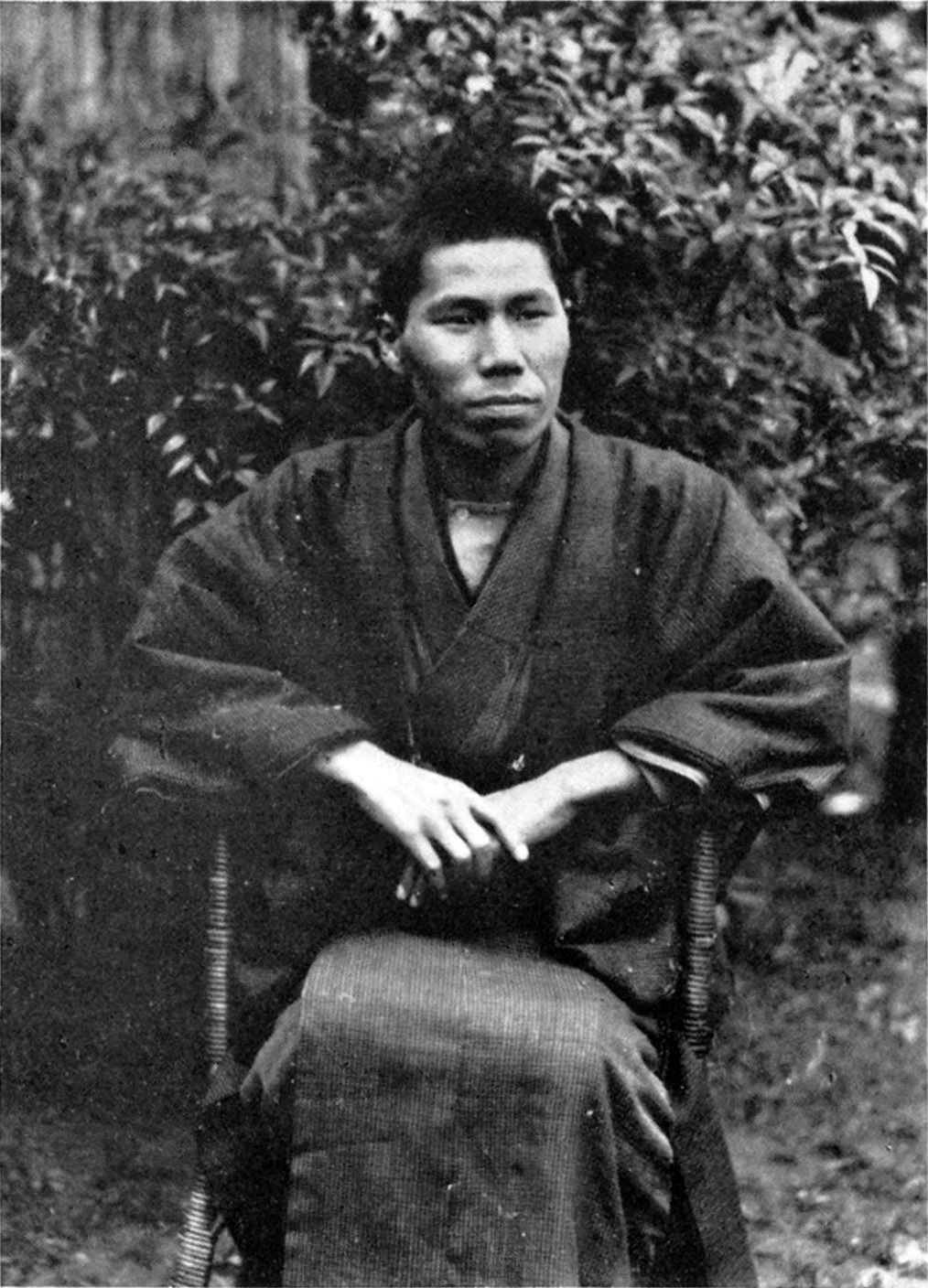

Most people who have read Lemon are probably wondering exactly what sort of person could write something so delicate in nature. They might be shocked upon seeing pictures of the man, though, because there’s nothing “delicate” about how he looks.

The cafe at Kyoto Maruzen has a Kyoto-only item on its menu which is named after the novel. Priced at a somewhat unappealing 700 yen, I have never eaten it myself despite visiting Kyoto Maruzen quite frequently. (Well, it’d be difficult for me to have tried it considering I have never actually stepped foot inside the cafe.) However, there is some information publicly available about said item on the restaurant review site Tabelog.

The silhouette is exactly like a lemon, and as the flavors of its three layers—sour lemon jelly, lemon sour cream, and lemon sponge—spread within your mouth, it gives you precisely the right amount of sweetness and tartness.

Come on. That sounds so elegant, there’s absolutely no connection between that and Kajii Motojiro.

Many commentators have made remarks about Kajii’s physical appearance. It isn’t pretty. They describe him not as “rugged” or “wild” or things along those lines, but literally as “an ugly man.” Now, speaking myself as someone possessing a face whose standard deviation score is relatively close to Kajii’s, I just feel like telling off all those critics. “Could you say that to the man after looking in the mirror yourself?!”

The sad thing is, they probably could. Poor Kajii…

But while everyone always has a field day teasing the man about his looks, author and critic Koyano Atsushi points out on his blog how little criticism Kajii Motojiro has received in regards to his actual writing. Even bearing in mind how he didn’t leave behind a large number of works, and despite the fact that he was by no means a mainstream writer, there has still been remarkably little criticism directed towards his work.

Why is this the case?

As someone with no literary background myself, I might be inclined to say it’s only because the critics find nothing to envy about his looks. I don’t know if history would’ve turned out differently had Cleopatra’s nose been 3cm taller, but I honestly do believe history would have changed if Kajii Motojiro had only been, say, 30% more good-looking.

Aside from his literary qualities, another thing about Kajii that doesn’t get alluded to negatively very often is his conduct. Nevertheless, it must be said that in all likelihood he was someone who would have been a major nuisance to be around.

First and foremost, this guy was a bad drunk.

This time around, we are going to learn from Kajii how to handle a scenario that most everyone has surely experienced in life. This is a method of dealing with those situations where you have hardly had anything to drink yourself, but the other party is absolutely bladdered.

Born in Osaka, Kajii attended Osaka Prefectural Kitano Junior High School (now: Osaka Prefectural Kitano Senior High School), and then went to Third High School (now: Kyoto University Faculty of Integrated Human Studies). At 23, he was admitted to Tokyo Imperial University (now: University of Tokyo), thus making his way to the capital.

In his book Kajii Motojiro no Koto, friend and novelist Tonomura Shigeru, who would later go on to become a recipient of the Noma Literary Prize and the Yomiuri Prize for Literature, reflects on Kajii following his move to Tokyo.

Kajii would get drunk with us in places like Lion and Printemps in Ginza, or Hyakumangoku out in Hongo. We were always up to foolish antics, like crossing the Shinbashi bridge girder or stealing train drivers’ name tags and getting chased by them.

However, by then he was no longer the person he had been in his Kyoto days—back when he was furiously dedicated only to wandering between states of mental anguish, desperation, and regret.

Bridge girders and train drivers’ name tags—already he sounds like quite the sad sack. But apparently, this was nothing compared to his “Kyoto days.” So then one might ask: what exactly did he get up to in Kyoto? I’ve got a bad feeling about this…

Another essential figure in telling Kajii’s story is someone who, like Tonomura, later became a writer: Nakatani Takao. The reason Nakatani is so important to the story is because because he did not drink at all. In other words, it means he can give us an impartial, objective eyewitness account into Kajii’s behavior.

In his book Kajii Motojiro, Nakatani remembers:

I think Kajii was able to feel at ease when he was around me, allowing him to act without restraint.

“Acting without restraint.” That’s definitely one way to put it.

For example, one time when Kajii was 21 years old, he went out with his friends on a summer evening to see if they might be able to see some fireflies. They did not find any fireflies, so instead they went to a bar where they drank and sang songs. A pretty ordinary story thus far. But, of course, the story doesn’t end there.

He was going around, spitting in between the scrolls hanging on the alcove. Then, he walked over to the bowl for washing sake cups, and he started washing his private parts with the water from the bowl. It was absolutely disgraceful behavior.

Then, as we were on the train making our way back home, he began violently yelling, “Hey, we didn’t see any damn fireflies! Let’s turn back!”

There’s so much to say here, I don’t know where to begin. I suppose I can only ask: did your parents not teach you to wash your private parts in the bath?

Needless to say, that wasn’t the only time he went off the rails.

It was around this time that Kajii’s drunken rowdiness started to become more violent in nature. He’d be doing all these things… Throwing beef into the kettle at the roasted chestnut shop, knocking over soba noodle food carts… He was becoming somewhat deranged.

More than just “somewhat,” most would agree. This was criminal behavior. His rampages were approaching levels of terrorism.

To make matters worse, despite acting with complete reckless abandon, the next day Kajii would never have any recollection of his misbehavior. The second Nakatani began recounting to him his previous night’s acts of barbarism, Kajii would suddenly start sulking, saying, “When you tell me stuff like that, it makes me feel like doing something even worse next time.”

Absolutely zero remorse.

Kajii’s favorite party trick when he got pished was throwing tantrums. One night, he was on his way home with Nakatani and a third person after they’d been out drinking. An incident occurred.

“Let me lose my virginity!”

While shouting at us in anger, Kajii laid there motionless on his back on the street with the tram line in Gion. I can’t say I wasn’t feeling somewhat hesitant about the idea, being stone-cold sober myself. […] But the two of us then got Kajii up, and we took him to the nearby red light district.

But when the woman appeared, Kajii suddenly began vomiting and just generally giving her trouble. It almost seemed like he was intentionally trying to harass the woman, with this being his final act of resistance.

Then, finally, it seemed like his resistance broke down.

Lying down on a busy main street while throwing a tantrum about how you want to lose your virginity, yet suddenly resisting by vomiting and refusing to take off your pants…

While one wants to tell him to just shut up and get it over with, Kajii still had even more irritation to dish out.

Kajii seemed to feel remorseful about his experience at the red light district. Afterwards, he would frequently vent his feelings about that night, almost as if he was cursing it.

Again, while one wants to just angrily yell at him and ask him what his goddamn problem is, that was surprisingly not Nakatani’s reaction.

He was telling me all these things. “I no longer understand what it means to be pure!” “I’ve become corrupt!”

But his words didn’t mean anything to me.

The lesson here is: it is best to not pay any mind to what drunks tell you.

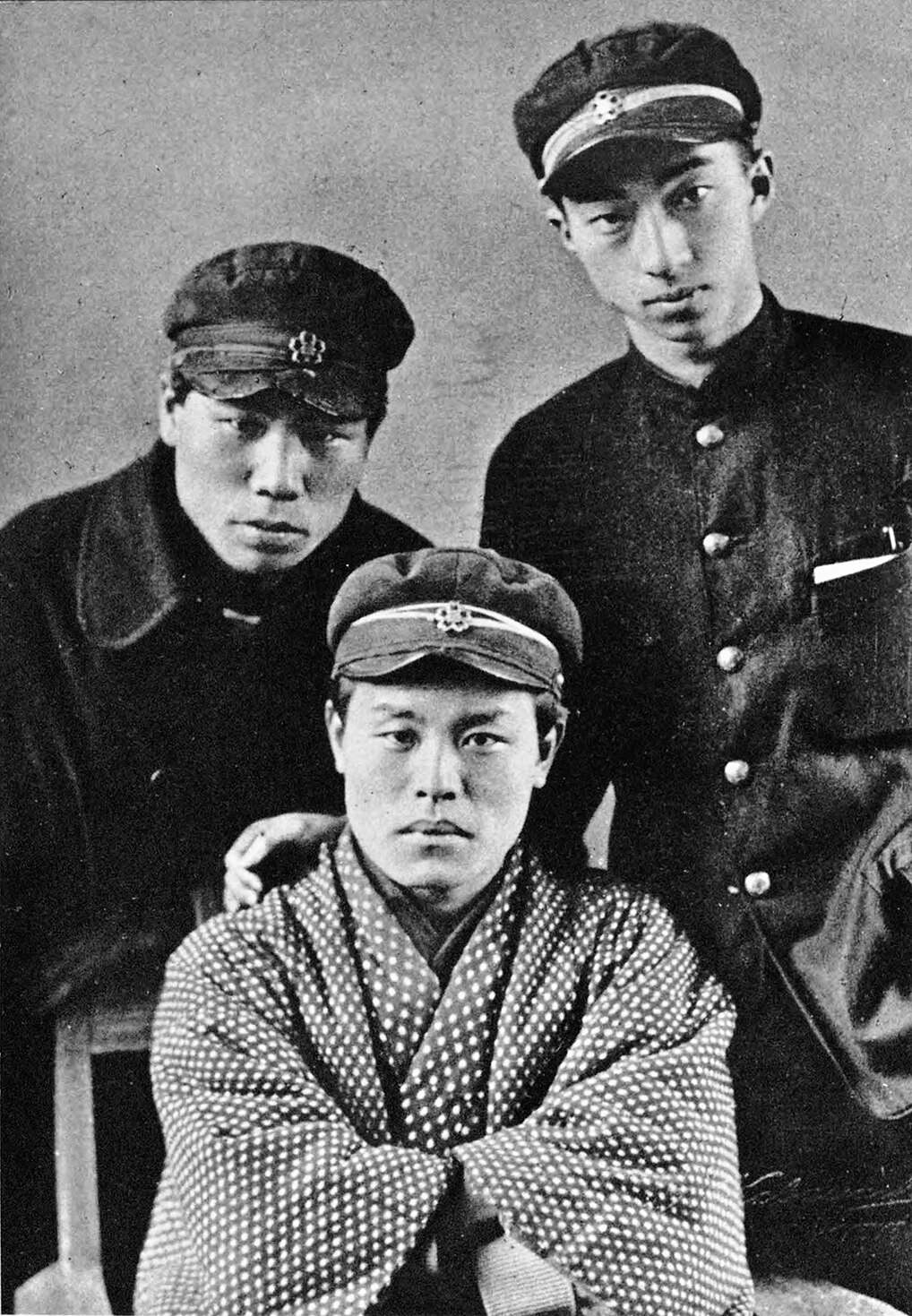

I’m not saying you shouldn’t humor them in the least, but rather to do so only to a certain extent while also not taking their words to heart. In his book Miotsukushi, the above-mentioned Tonomura speaks of Nakatani as follows: “Nakatani doesn’t drink at all. But no matter how long our drinking sessions drag on, he never leaves us behind.”

Even while Nakatani may have helped Kajii and the rest of his drunk friends carry some poor merchant’s signpost to some far-off place in the middle of nowhere, that didn’t mean he chose to participate in all of their barbarism. If they were doing something that seemed like way too much trouble, he would simply detach himself.

His behavior is a model example of how to act with your polluted colleagues when you are not drunk yourself.

(L-R) Kajii Motojiro, Nakatani Takao, Tonomura Shigeru

We have now identified Kajii as one downright bothersome chap.

But on the reverse of that bothersome side of his, there was a deeply serious side to him as well. It is this part about him that made it so that future generations, like ours, would know about him.

Looking back on their days at Third High School, Nakatani says that whenever they had a test coming up, he would personally just try for 60 points (the passing score) whereas Kajii was always aiming for the full 100 points. Kajii, always the perfectionist, would go and buy all the reference books he could get his hands on before tests, collecting notes from every possible source. Sadly, he was too preoccupied with this material-gathering process—by the time he actually started studying, the test would already be upon him. As a result, his test scores were never that different from Nakatani.

Despite those looks of his, he was in fact very picky about what he ate and carried with him. He was always drinking Lipton Black Tea, and eating steak at some fancy Ginza cafe. He was also fond of French-made soap and pomade. “Pomade? With a face like that?” You’d think so, but Kajii would comb his hair with pomade so systematically that each individual strand of hair stood out conspicuously. That should tell you how meticulous he was.

While it kind of feels like his perfectionism and exceptionalism didn’t really get him anywhere in his college life, it definitely started to work in his favor when he began writing. While visiting the Yugashima hot springs in Izu—partly also for tuberculosis treatment—Kajii’s perfectionism surely came in handy when he helped to proofread Kawabata Yasunari’s The Dancing Girl of Izu.

Despite his life having been cut short, Kajii’s uncompromising aim for perfection with each and every single work of his would lead to his name going down in the annals of history.