Back in February 2011, Taiyo Someya wrote a four-part column for HMV ONLINE to commemorate the release of Tokyo Utopia Tsuushin. In it, he details the early history of Lamp and their journey towards the release of what was at the time their latest album.

Original text: Taiyo Someya (parts one, two, three & four)

English translation: Henkka

Lamp online: website, label, blog, Facebook, Twitter, Spotify, YouTube, SoundCloud, Instagram

You can buy Lamp’s music directly from the band, both physically and digitally, on Bandcamp.

With Lamp’s previous album, Lamp Gensou, they quite literally to its name gave us an album full of fleeting, illusional beauty; a sound world drawing a line between music you’d normally expect to hear in this day and age; an innovative masterpiece in modern pop music. Hachigatsu no Shijou, a limited edition EP released in mid-2010, had summer as its theme, and on it they once again portrayed the fleetingness of the seasons in its lyrics, along with sound imagery that made for a perfect companion to the words. It showed us the world of Lamp richer than ever before, opening new possibilities for them as a band.

With Lamp’s previous album, Lamp Gensou, they quite literally to its name gave us an album full of fleeting, illusional beauty; a sound world drawing a line between music you’d normally expect to hear in this day and age; an innovative masterpiece in modern pop music. Hachigatsu no Shijou, a limited edition EP released in mid-2010, had summer as its theme, and on it they once again portrayed the fleetingness of the seasons in its lyrics, along with sound imagery that made for a perfect companion to the words. It showed us the world of Lamp richer than ever before, opening new possibilities for them as a band.

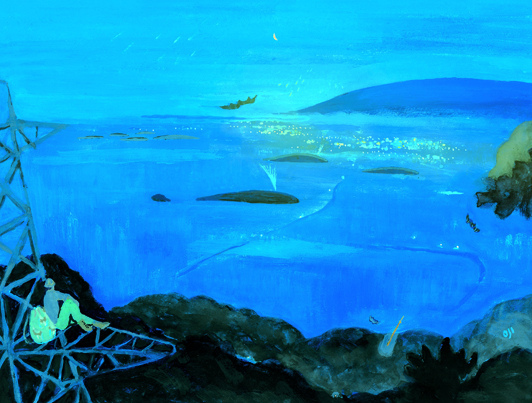

Now, Lamp are releasing their long-awaited new album, Tokyo Utopia Tsuushin, recorded alongside the Hachigatsu no Shijou EP with about a year and half of work behind it. It’s something that needs to be called the “rebirth” of Lamp; a condensation of tighter rhythm arrangements and even more of the characteristics that make up the “Lamp sound.” It features their usual brand of beautiful lyrics that capture places in time: the cold and the warmth of winter; nostalgic sensations we’ve all once experienced; a man and a woman in an imaginary place, in an imaginary town. Those lyrics are placed on top of a new sound, making for an 8-song masterpiece of the highest order. The sounds on it show an exceedingly distinctive brilliance among the current music scene; a kind of originality that — even looking back — is something only Lamp could’ve produced. It’s something on a whole new level altogether. —HMV

No matter how you slice it,

they’re a band just brimming with the

freshness of someone who does their own thing.

And that’s regardless of the maturity that’s

instantly audible in their musicianship.

There aren’t many people like that out there.

That’s what makes them so great.

Tomita Lab (Keiichi Tomita)

Part One

By the time I started high school, I was constantly thinking about music.

My father owned this small rehearsal studio near Tokyo when I was little. I say “studio,” but what it really was was just a room inside an apartment building. He always brought the customers coffee — a sign of the times, perhaps.

As to the type of business he was running there, I guess it wouldn’t be too far off to call it “managerial” in nature. Soon after my little sister was born, he could no longer provide for our household with just the studio and he had to close it down. There had been complaints from other tenants of the building, but the main reason for its closing was that it began to get less customers after a major company opened their rehearsal studio in Kichijoji.

My old man was constantly playing the guitar when he was home. The sounds you could often hear at our house included those of Jimi Hendrix and The Beatles, Bob Marley and Earth, Wind & Fire, Peter, Paul and Mary, and Fujio Yamaguchi. For the most part I did like what my parents listened to, but to this day I still don’t care much for Janis Joplin or Aretha Franklin.

Years before I was born my father lived in Kyoto for a time, playing with Fujio Yamaguchi in a band that later became known as Murahachibu, but he later ended up moving back to Tokyo. My mother continues to look out for Fujio-kun (as we call him at the house) and they still keep in touch. According to my mother, my old man really loved music. She says he took his music very seriously — almost as if she was saying I need to be more serious about mine.

I was born when my old man was 31 years old — the same age as I am now. That’s a strange thought.

I was your average young boy. I liked sports and didn’t have much of an interest in music, much less picking up a musical instrument myself. The thought never even crossed my mind. I only learned some Bayer very briefly when I was a second grade elementary schooler after my little sister started taking piano lessons.

I did like singing at home though. According to my parents, I loved “Ame” and would apparently always get really into it when singing it.

I bought my first CD with my own pocket money when I was in third grade of junior high. This was considerably later than all my friends; I didn’t watch a lot of TV growing up so I never got much exposure to kayou kyoku or J-pop. Sure, I liked some of the hit songs the girls in my class were singing, but I’d forgotten all about them by the time I got home — and all the music playing at home would be older Western music.

Perhaps it was because of these circumstances that when I saw this program on TV with the chart-topping hits at the time of my high school entrance exams, they sounded really fresh to to my ears. It made me think I’d like to try writing songs myself, too. I didn’t know even the very basics of songwriting, but when I heard those songs, I still found myself thinking about how I would do them differently if it was me playing them. I think that’s what originally made me interested in writing songs.

It’s not that I wanted to play an instrument per se — I just figured it’d be very inconvenient to write songs without being able to play one. So, I decided to pick one up, and that’s when I first touched my old man’s guitar — something I’d previously only watched and listened to. Before long, I got my parents to buy me an electric guitar. I think this was just before I started high school.

My high school was a university prep school in my prefecture. It was pretty lenient with the boys and girls all mingling with each other quite freely. I joined a “Folk Song Association,” a sort of club for people who liked light music. For some reason everyone from my year in the club was a fan of Western music — listening to Japanese music was considered lame and uncool. All my friends there were skilled at playing their instruments, too.

That’s when I first started buying and listening to Western music. I liked artists such as David Bowie, Nirvana, Smashing Pumpkins, Oasis, The Beatles, and Simon & Garfunkel. I listened to other stuff, too, but it was all popular bands you could read about on the magazines, and I’d find out about them through my friends’ recommendations. Back then I used to frequent a place called Kashiwa Street that had a Virgin Records, Disk Union, and Shinseido. I’d listen to all kinds of albums there and buy the ones I liked.

In my second year of high school, Nagai (fellow Lamp member) — one year my junior — joined the Folk Song Association I was a member of. All my friends who were my age tended to prefer rock music, and no one besides me and Nagai really “got” the stuff with more harmony, like The Beatles or Simon & Garfunkel. I think me and Nagai having this in common was originally the reason us two started talking more.

The first time I saw Nagai doing a solo version of “Hey Jude” in our music class, I just thought to myself “this guy is something else.” I got him to show me his method of practice and how to sing the background vocal, line by line, and it was shocking for me to see how his way of practicing was completely different from everyone else in my class.

I knew that music was what I wanted to do with my future, and once I got to know him, I asked Nagai to join me on that path.

Around my third year of high school I was starting to feel unsatisfied just being in a cover band, so I put up posters around rehearsal studios saying we were recruiting members, and that’s how I started my first band that played original material. I pretty much forced Nagai to join, and he became the rhythm guitar player — we already had a vocalist. We ended up with a total of five members, with me as the songwriter and lead guitarist.

Suffice to say, looking back and listening to our stuff now, it sounds absolutely terrible. Still, the experience I gained from doing the songwriting and those band arrangements is something that helps me even today. We made simple demos and played live shows, but before even a year had passed, Nagai quit the band, saying he no longer had the motivation for it.

I said “well, there’s no point if Nagai’s quitting,” and I quit, too. And with that, the band broke up.

Part Two

In my third year of high school I was faced with the decision between just entering the university affiliated with my high school, or taking entrance exams to get into a better one. My grades weren’t awful, and besides, I’d lost all motivation to study at this point, so I took the easy way out and joined the affiliated university, deciding to skip the exams.

I’m not sure why, but Nagai, too, chose the same route, and a year later we were in the same department of the same university.

The first friend I made in university was a classmate of mine, Yuki Yamamoto. Well, if we’re being honest, he was actually both the first and last friend I made in university. He now works at the main office of HMV where he’s in charge of the jazz department while also promoting Brazilian and Argentinian music. I’m not sure if this column, too, was commissioned by him.

Being one year my senior he was extremely knowledgeable about music trivia, and me being the country bumpkin that I am, he kindly introduced me to lots of new music. I think I was borrowing two or three CD’s from him every week, and after school we’d go around all these record stores in places like Shinjuku, Shibuya and Jinbouchou. I got addicted to all kinds of music recommended to me by him, and I’d then introduce all my new favorites to Nagai.

Around that time I was interested in 60s music. I got started with soft rock and bossa nova, gradually finding my way through 70s SSW and soul, AOR and MPB. Even now I’m brought back to those times at school when I listen to stuff like Roger Nichols, Millennium or Sagittarius. Among other 60s Western music I was also listening to stuff like The Velvet Underground, Beach Boys and Georgie Fame a lot. As for bossa nova, I was all about Caetano & Gal’s Domingo and Joao Gilberto’s Getz/Gilberto. Other stuff I often listened to included Kenny Rankin’s Silver Morning and Nick Drake’s Pink Moon.

For two years after starting university I spent all my time listening to music, but I wasn’t involved in any other musical activities.

Every now and then Nagai would come over and we’d use an MTR (multitrack recorder) to record ourselves doing Beatles songs and originals. We toyed with the idea of starting up another band, but we were having trouble coming up with enough ideas just by the two of us. It felt like we needed one more person, but we weren’t having any luck finding someone suitable.

In the winter of my second year in university I went to hang out at the house of an old friend from my high school days. He’d been in the Folk Song Association with me and we’d been classmates for two years.

I brought him a mix tape of all the music I was listening to around those days. I’m pretty sure it was full of stuff like mods, French pop, bossa nova and 60s Western music. I asked my friend if he knew anyone who could sing and who liked similar kind of music, and he told me he did know this one person. I immediately got him to call them right then and there, and I got to meet this band member prospect that very day.

That person was Kaori Sakakibara (fellow Lamp member). My friend and Sakakibara had known each other since elementary school and were great friends. And sure enough, talking to Sakakibara, our interests were similar. Plus, there was just something about her that told me she was the one we were looking for.

I didn’t get to hear her sing that day, but I intuitively felt like me, her and Nagai would make for a great band, and I phoned Nagai to let him know about this meeting.

And before long, the three of us had formed a band.

For the first year of our band’s existence, I wrote all the songs and we slightly arranged them before then recording them. That was the only real activity we had as a band. We’d work on our songs a little bit on the days we got together, but the rest of the time we’d mostly just listen to music, read manga or magazines, and eat. You know, the typical stuff kids do.

Then one day we saw a flier at a Shibuya record shop advertising a bossa nova live show, and all three of us went there together. It was an all-night event and we were still young, so even just the concept of “all-night” seemed exciting to us.

The show was held in a bar called Magnacy in Nishi-Azabu. I don’t remember the exact details of how it went down, but for some reason the bar owner was interested in our music, so we played him one of our demo tapes. He seemed to like it, and as a result, we ended up doing these regular live/DJ events at the bar. The university friend I introduced earlier, Yuki Yamamoto, was the DJ, and by the four of us we held an event called “Primavera” on a number of occasions.

We had to play live so we realized we needed a band name, so we decided to call ourselves “Lamp.” It was a small bar, and each time the audiences would mostly just consist of ten or so of our acquaintances. It was an extremely small-scale event.

Part Three

I wasn’t too crazy about job hunting. It’s not that I didn’t want a job; I just wasn’t exactly in a hurry about finding one.

Meanwhile, as I was looking for employment, Lamp recorded a four-song demo MD. This demo included songs that would later get an official release, such as “Amaashi Hayaku,” “Utakata Kitan” and “Hatachi no Koi.” We sent this to several so-called major labels. I knew our chances of getting a positive response were low, but I figured we’d at least get some response.

I was in the middle of a nap when I received the first call back from one of those companies. They said they were interested and that they wanted us to come over and talk.

As for the job hunt, I’d done the final interview for a certain company and they’d tentatively told me the job was mine. That’s when I turned it down.

I’d always had confidence in our music, and now our music was actually receiving real feedback from real companies. This made me glad, and what’s more, it made me feel even more confident about the band. That’s why I ended up choosing music over the job offer.

But although we did receive several promising calls back concerning our demo, no matter where we went we only got vague promises: there were no real talks of actually putting out a release of ours with any record label at the time.

That, however, only made us even more determined and we made another demo, this time with ten songs. This was the year after I’d graduated from university. Looking back, I don’t think any record label would actually even listen to an entire ten-song demo. We might’ve been better off sticking to four.

It was around that time we went to a certain DJ event by the three of us. Sekine, a DJ friend of mine, told me that this person called Sakuma from Motel Bleu was there. I knew that Motel Bleu was the label that had released a CD by this band called Bossa51, so Sekine introduced us to each other and we gave Sakuma a copy of our ten-song demo that was fresh out of the oven.

The next morning I received an email from Sakuma that simply said “I listened to it. Let’s talk soon.” I was surprised at how brief and rude the email seemed at the time.

It wouldn’t take long for me to find out that his emails are always brief.

And so we talked. We met at this coffee shop in Shibuya and I remember us talking about Michael Franks. It seemed like around this age whenever we’d speak up about the kind of music we liked, we’d always get a comment along the lines of “it’s so nice to see young people such as yourself listening to all kinds of music!”

Talks with Motel Bleu proceeded favorably, and finally in September of that year (2002), Lamp began to work on its first album, Soyokaze Apartment 201.

The recording took place in Inagi, in the home studio of recording engineer Satoshi Tamano who was an acquaintance of Sakuma’s. It was a fairly dated Japanese-style house. Old walls, creaky floors, doors that wouldn’t quite close properly, a spacious garden. We fell in love with that landscape instantly. It felt like it suited us perfectly.

It was pretty bewildering at first working on something with people other than us members present. Near the end of the recordings, we the band and engineer Tamano got into an argument over how we wanted the album to sound, and work on it came to a standstill. It was around six people in the room, all sitting down on the tatami mats with their backs straight, exchanging opinions.

We wanted a cool sound for our album, something like Erig Tagg or Leroy Hutson, but Tamano told us that our playing wasn’t at a level where a sound like that would work for us. So we ended up not getting the sound we’d originally wanted. Listening to the album now there was definitely some truth to what Tamano was saying, but at the time I couldn’t understand a word of what was coming out of his mouth.

The recordings took four months. Somehow we managed to finish six songs and the release was set for April 9th, 2003.

It sold an amount of copies that was apparently quite adequate for an indies pop band, but for us it wasn’t a number that satisfied us. The way most people seemed to understand or perceive us was that we were “stylish” or “cafe music,” but they were only seeing the very surface of what we wanted to express. It strongly felt to us like everyone saw us in an entirely different way than we did. There was none of the widespread acceptance of our music that we’d been expecting.

Our second album, Koibito e, was made with those built-up feelings growing inside us. I think songs like “Hirogaru Namida” and “Ame no Message” could’ve been difficult to grasp for people who’d heard our first album.

Sometimes negative feelings can give you even more strength to work. That’s the sort of rebellious spirit I am, at least. And yet, the feedback we received for our second album was once again not quite what we’d been hoping for — though some people did seem to get it. It’s the same thing with unfamiliar chords: if it’s something you haven’t heard before or something you’re not used to, often times you don’t really receive it well.

We recorded a total of three albums using the same studio and the same methods with engineer Tamano.

We lived around northern Chiba and southern Ibaraki, so it would take us around three hours to get from there to record in Inagi, Tokyo. It was like a small excursion every time. We’d make the trip around twice a week for three years straight, without almost any breaks.

I still remember how I’d get in my car at 10 in the morning and pick up the other two, and we’d get to Inagi by 1 in the afternoon. Each time we’d record from 1 PM until midnight, or 1 or 2 in the AM, and then we’d drive back home. Looking back, it was pretty incredible. By the end of the recordings for our third album, Komorebidoori ni te, I was sleeping in the car some nights.

When that album was finished, we just said “if this one is no good, we have nothing more to give.” We felt like we’d done everything we could to make it as perfect as we possibly could, and yet, we’d become so consumed by its production that we couldn’t even tell anymore if the music on it was really good or not. I think it might be because of this that when you read some of our interviews from around that time, we might’ve sounded really pessimistic.

Komorebidoori ni te was done, and we felt like we’d given it all we had. We didn’t want to work on any more music with the methods we’d employed up until that point. We told this to Sakuma from Motel Bleu, and then we started looking for a new way of doing things.

Part Four

When Lamp was formed it was always a simple trio, with me writing the songs and playing the guitar, and Nagai and Sakakibara on vocals. At that point, Nagai hadn’t gotten very proactive about songwriting yet. Well, not that he’s very proactive about it even now. But I gradually drove him to write more as time went on. I just had a feeling the band wouldn’t last otherwise.

“Kimi wa Boku no Koibito” (from Ame ni Hana) is a song Nagai wrote before Lamp’s formation. I first heard it right around the time we’d met Sakakibara, and it was a big hint to me: I thought to myself that was basically going to be the style we were going to go for. And that style was, in short, bossa nova mixed with Japanese-language pop. Hearing it, I could clearly see Nagai’s talent for songwriting.

I thought we’d be an even better band if some day we could record and perform not only my songs, but those of Nagai as well. And by the time we began work on our first album, Soyokaze Apartment 201, in September 2002, Nagai had written three more songs: “Ai no Kotoba,” “Kaze no Gogo ni” and “Konya no Futari.” Unlike now, the way it worked back then was that the initiative wasn’t necessarily always with the main composer — for example, many of my ideas went into those three songs, too.

I didn’t think it was necessary for an album to have a single; I just thought it needed that one great song to really lead it. For Soyokaze Apartment 201 that song was “Kaze no Gogo ni,” for Koibito e it was “Hirogaru Namida,” and for Komorebidoori ni te it was “Tsumetai Yoru no Hikari,” all masterpieces penned by Nagai. For the most part, I would then write the rest of the material as the three of us together solidified the albums further.

By the end of Komorebidoori ni te, Nagai was quite exhausted. It looked like making another album with a lead track written by him wasn’t going to be possible any time soon.

When that album was done, I began to think about the next one. Up until that point I’d been relying on Nagai’s songs, but I was starting to feel confident about my own material and I hoped that I would finally be able to write songs that could be the lead tracks on future albums.

Starting in late 2005, I first wrote “Ame Furu Yoru no Mukou” and “Mood Romantica,” and then in 2006, “Kimi ga Naku Nara” and lastly “Kuusou Yakan Hikou.” I tried to remain very aware of the overall balance of the songs as I was working on them. I began developing a self-consciousness as a composer around this time.

It was also around this time that I came up with two ideas.

The first one was that I wanted to make an album full of the kind of very graceful, traditionally Japanese-influenced songs I’d been wanting to write ever since our formation. Two songs I’d written right around the time we’d started our activities — “Utakata Kitan” and “Hatachi no Koi” — gave me this idea. I wanted to make a whole album with that sort of mood to it. At that point I don’t think I had a name for this album yet, but I’d already gotten a feel for how I wanted to approach the sound production for it when we recorded Zankou‘s “Mood Romantica No2.”

The other idea was that I wanted to make another album that showed even further musical evolution than all our previous releases. And as I was thinking that, I just happened to come up with the album title of Tokyo Utopia Tsuushin. Both of these albums were meant to be very different from each other.

I introduced these two themes and concepts to Sakuma and the members, wanting to get to work on them right away. But since recording two albums at the same time was just too enormous of a workload, we instead decided to make the albums in order.

As we were working on the first one, Lamp Gensou, we also recorded an album with Daniel Kwon. We were so fascinated by his music we actually suspended the production of our own album just to work with him. We’re pretty much amateurs ourselves, but Daniel was even more so, and we all enjoyed those “everything goes” recording sessions. Helping support and produce the recording process for someone like Daniel who is just so full of original ideas ended up being a really positive experience, and it had considerable influence on our own material, too.

There was another slight change of plans along the way when we had the sudden idea of doing Hachigatsu no Shijou. We thought it might be a little arrogant of us calling a release with just five songs on it an “album,” so in the end we ended up calling it an “EP” instead. But for us the making of it genuinely felt like our fifth “rite of passage,” and content-wise, too, I’m not at all embarrassed to consider it an album in its own right. We’ve thus since reconsidered our stance on it, and we now like to think of it as our fifth album.

And then we finally arrive at Tokyo Utopia Tsuushin.

Now in February 2011, five years after its conception, we’ve finally managed to release this album full of all those accumulated ideas and music of ours.

As to what the future holds for Lamp, we don’t even know ourselves.

We can’t picture even our very next step at this point.

We feel both excited and nervous to find out.

Taiyo Someya (Lamp)

Bonus

Also in commemoration of the release of Tokyo Utopia Tsuushin, Lamp held a listening event for the album in Shibuya in February 2011. In this article from webDICE, you’ll find a summary of the track-by-track comments they gave on the album at this event.

Original text: Kenji Komai (original article)

English translation: Henkka

Lamp listening event & mini-live @ Uplink Factory, Shibuya

(L-to-R) Yusuke Nagai, Taiyo Someya, Kaori Sakakibara

Taiyo Someya: Lamp released Komorebidoori ni te in 2005, followed by the compilation of previously unreleased songs, Zankou, in 2007. But between those two releases I’d already come up with the basic ideas for Lamp Gensou (2008) and this new album, Tokyo Utopia Tsuushin. Even before I’d written most of the songs on Lamp Gensou I was already set on releasing this newest album at some point, and with that in mind, we released both Lamp Gensou and Hachigatsu no Shijou (2010). So in other words, this album has been in the making since 2006.

1. “Kuusou Yakan Hikou”

Someya: This song has two different drum parts; one on the left, one on the right channel. This is something I heard on a song by Venezuelan artist Aldemaro Romero and wanted to try out on one of our songs, too. Brazilian music is something I originally got hooked on because of the harmony. Folk music, for example, most often features the triad of Do/Mi/So, but Brazilian music is made up of Do/Mi/So/Shi. I was drawn to both the complexity as well as the beauty of it, and the more I listened, the more I found myself becoming hypnotized by the rhythm, too. I think you might be able to easily spot plenty of such parts on Tokyo Utopia Tsuushin, too.

2. “Kimi ga Naku Nara”

Kaori Sakakibara: This one takes a progressive turn near the end. We also used a different rhythm arrangement for the first and second verses, the hi-hat in the bridge… The configuration of this song is so interesting, I don’t think you’ll get bored of it easily.

From “Tokyo Utopia Tsuushin”

Photo: Ouji Suzuki

Yusuke Nagai: This one is a pretty rare one for us considering how we usually first record the basic track live and then record overdubs over that. I think there’s a very audible difference from the “group sound” we’ve usually had up until now.

4. “Tooi Tabiji”

Someya: I got so carried away with those bends on the guitar solo duel with Nagai that I went way off-key. (laughs) My parents both like rock, stuff like Jimi Hendrix, and that’s how I originally got started with music, too. But after I met Nagai and Sakakibara I started thinking about what it was that I could bring to a group with us three, and at the time I figured “rock” wasn’t that thing for me. But in more recent times I’ve been listening to lots of the rock music I used to listen to and play myself, and sometimes I think it’s gradually starting to appear in our music as well.

5. “Kimi to Boku to no Sayonara ni”

Someya: The album title includes the word “Tokyo,” but there aren’t really any direct allusions to the city in the lyrics. Lamp’s lyrics always have a good dose of ambiguity that’s not even intentional — it always just turns out that way. Well, they’re all love songs, but none of them are based in reality. If I had to name one thing we generally want to express with the lyrics, it’s a kind of “sense of vagueness.”

Sakakibara: Lamp’s lyrics often have a sorrowful foundation, coupled with some components that remind you of the seasons. What I mean by the latter is, if you think about the Frog Poem for example, I think that poem might seem overly simple to a foreign person who doesn’t understand Japanese. It’s like “wait, that’s it?” But a Japanese person reading it will instantly recognize the season in it; they’ll feel more than is actually written in the words. It might be a bit of an exaggeration to call it something “beyond” the lyrics, but there’s something a little bit like that in our lyrics that I think some of our listeners appreciate.

6. “Kokoro no Madobe ni Akai Hana wo Kazatte”

Nagai: I like Todd Rundgren, so I played all the instruments on this one by myself and tried to make it have the same kind of feel as his music, and somehow I got the song to take form. I really like this one.

From “Tokyo Utopia Tsuushin”

Photo: Ouji Suzuki

7. “Mood Romantica”

Sakakibara: This samba version of the song was how we originally envisioned it; “Mood Romantica No2” found on Zankou was actually a rearrangement based on this one.

Someya: By the way, I just wanted to mention something about the interludes on this album (the endings of “Hiyayaka na Joukei” and “Kokoro no Madobe ni Akai Hana wo Kazatte“)… There’s this album called Clube da Esquina (1972) by Milton Nascimento and Lô Borges, and on it there are two songs called “Cais” and “Um Gosto de Sol” that feature the same theme with different arrangements. We wanted to try doing the same thing on our album as well.

Someya: I love 60s and 70s music so obviously I don’t have anything against the album format itself, but I do wonder if there’s any point to most albums that are released nowadays. When we craft an album, we try to make it so that each successive song builds on the previous one and makes it sound even better. Well, with that said, though, even the majority of all those “concept albums” released in the 60s weren’t actually very conceptual per se. In any case, I think that everything about our latest album down to the artwork is something only we would’ve done, and for me it sounds like a whole, complete piece of work.