Kyoto Film Studios and Period Drama

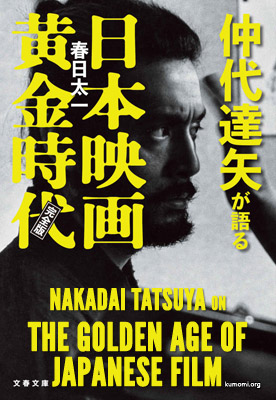

“Conflagration,” “Odd Obsession,” “Three Yakuza,” “Harakiri”

When the world of Japanese cinema was in its “Golden Age,” three companies—Daiei, Shochiku, and Toei—operated their own film studios in Kyoto where the majority of the works produced were period dramas.

In this chapter we trace Nakadai’s footsteps in Kyoto, focusing especially on all those period dramas.

Ichikawa Kon & Ichikawa Raizo

Nakadai’s first film shoot in Kyoto took place in 1958 at Daiei Studios Kyoto for the film Conflagration. Based on Mishima Yukio’s novel The Temple of the Golden Pavilion, the film was directed by the up-and-coming Ichikawa Kon who had received critical acclaim for his ’56 film The Burmese Harp. The leading actor, Ichikawa Raizo, was from a noble family of kabuki actors. He was at the height of his popularity at the time, famous for his clean-cut looks—a handsome star actor.

That all took a sudden turn with this film, however, when he gave an amazing performance as a reserved student with a gloomy personality caused by his stutter. It’s the role that allowed him to free himself from being an actor who relied on his looks, to an actor who used his acting skills. Here, Nakadai plays the part of the protagonist’s friend, a man suffering from polio-induced paralysis on the right side of his body.

The atmosphere between film studios in Tokyo and Kyoto was completely different. Toei’s studios in Tokyo were extremely modern and stylish, but over in Kyoto—no matter if it was Shochiku, Daiei, or Toei—the staff and actors all had that old-timey, “old school” attitude. I personally felt a little scared going to Kyoto.

Once I got there, it was indeed scary. Well, I suppose it was even scarier later when I first went to Toei’s studios—the first movie I did in Kyoto was Conflagration, and that was for Daiei with Ichikawa Kon as the director so it wasn’t quite as bad. See, even in the context of Kyoto, Toei Kyoto and Daiei Kyoto had a totally different feel from one another. Compared to Toei, Daiei’s studios were a little bit less… “yakuza-ish.”

Me being a freelance actor, most of the films I’ve done I have been asked to do so directly by the director. In the case of Conflagration, Ichikawa Kon personally approached me.

The setting of the film was about two men with insecurities who live their lives in two opposite ways. It was very fascinating. I was handicapped and Raizo had a stutter. But while I did have that shortcoming, I used it as a weapon—I was a student with a nihilistic outlook on the world. Raizo, on the other hand, played this very introverted, naive role. There was camaraderie but also competition between the two characters—I guess you could say we bullied each another. Well, to be fair, my role was pretty much just all bully. Playing those sorts of roles with strong insecurities is in my nature, so I had a lot of fun doing that role.

Ichikawa Raizo was from the world kabuki, and he was very much an intellectual. He was similar to a shingeki actor—that is, he came across as a bit different from those people who I would call the old school Kyoto actors. His way of thinking, even just the air about him was very “modern.”

We would often drink together once we were done with shooting for the day. He was from a kabuki background and I was a shingeki guy—since we were two very different people shooting the same movie, we took the opportunity of discussing things like acting and the differences in our work. Even when we were drinking, he’d be very curious to learn more about the shingeki side of things. While we only appeared in that one film together, we got along extremely well. He felt that us shingeki actors were very “argumentative,” but then he himself could be pretty argumentative when it came to role preparation.

Director Ichikawa Kon produced works that went beyond everyday realism. Even in conversation, he would often exceed day-to-day realism in his way—the “Ichikawa Kon Way of Speaking.”

I’ll give you an example. In the case of Conflagration, before I went in for my first day of filming I took it upon myself to secretly observe people suffering from polio, watching how they walked and talked. However, on my first day when I did that scene where I make my first appearance at the playground, Ichikawa pulled me aside. “Nakadai, come here for a second. Your leg—try to walk almost as if you didn’t even have this part (below the knee).” In reality it’s not that pronounced, the way that people with polio walk. But for this reason, I enter the scene walking in a very exaggerated way.

He was also someone who could be very quick to insult you. He would ask you to do something in a certain way, you’d do exactly like he asked you to, and still he would happily declare how hopeless you were—in front of everyone. “You expect to get paid even when you’re so terrible?” That sort of thing. And yet, when he said those things he didn’t mean to be hateful in the least.

On the set of “Conflagration”

(L-R) Ichikawa Raizo, Director Ichikawa Kon, Aratama Michiyo, Nakadai Tatsuya

Back in those days, we would be sent the script for the movie about two months in advance, the actors would read it, we’d have a meeting where the director would explain to the actors what sort of a film he wanted to make, and then we would start filming. When it was time to begin, everyone knew the script. Thus, when we actually did start filming, no one would even have their script with them—we’d have thrown it away by then. This was true for Mifune, for Raizo… Everyone worked like that.

But this one time I wanted to check up on something, and so I was at the studio reading the script when someone slapped me on the back. I turned to look and it was Director Kon. “It’s too late to study it now, Nakadai.” He explained that he already had a pretty good idea of exactly how he was going to have me act when he had first cast me in the role.

A lot of directors were like that. “Casting is everything,” they’d say. That’s part of directing, too. First they’d say to the actor, “Just do it how you see fit. Give it your best shot. If it’s no good, then I’ll just know your limits as an actor. If something you’re doing doesn’t fit the role, I’ll let you know so you can stop doing it.” That was how all the great masters back then used to direct, whether it was Ichikawa Kon, Kobayashi Masaki, or Kurosawa Akira.

He was so good at directing newcomers, too. On another movie we did, there was this young actress who had a big role in it. Kon gave her his instructions. “When I say “action,” count to yourself “one, two, three, four,” and then gently close your eyes. “Five, six, seven, eight”—suddenly open them again.” She did exactly as he’d instructed her, and her acting in the film looked wonderful—it really conveyed that feeling.

In the following year of ’59, Nakadai appeared in another Ichikawa Kon/Daiei production, Odd Obsession, which was based on a novel by Tanizaki Junichiro. In this comical story about an older man who drives his wife and his young acquaintance to become intimate as he enjoys secretly observing their developing relationship, Nakadai played the young acquaintance in a devil-may-care fashion. He acted alongside two superstars in the film: in the role of the older man was Nakamura Ganjiro—who was later designed as a Living National Treasure—and in the role of his wife was Kyo Machiko.

Right around the time of Odd Obsession, they were beginning to switch from black-and-white to technicolor. Ichikawa Kon told me, “You know, someone with a beard as thick as yours isn’t going to be popular anymore once everything is in technicolor. You still have a five o’clock shadow no matter how much you shave, right? People are going to be able to see that sort of thing.” I remember getting this really heavy, pure white makeup getting done on my face. That was funny.

There was this “limpness” to my role in that movie… It was the most unpleasant, slug-like acting I ever did. I actually quite like that sort of thing. Sure, I can play the man of justice, too. But I really like doing characters that have some kind of a negative like that about them. Maybe it’s a personality deficit…

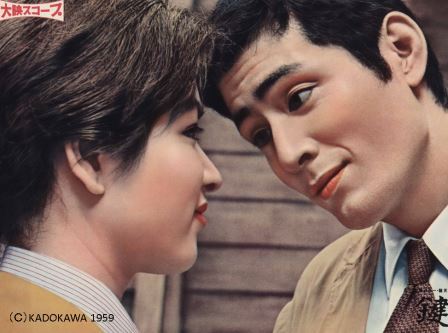

Nakadai in “Odd Obsession”

I found Nakamura Ganjiro to be just amazing. Sure, he was a leading figure in kabuki theater in the Kansai area, but he was extremely candid. There was zero sense of the social rules of kabuki or whatnot about him—he was exactly like his character in Odd Obsession. He even asked me, “Hey Nakadai, do you know of any red light districts in Tokyo?” It was the perfect role for him.

Meeting Kyo Machiko, she was so quiet and so very subdued—she gave me the impression of being the exact opposite of her role. And yet, you could just sense something emitting from her outward appearance; from her physique.

Daiei & Toei

At the time, Daiei Studios Kyoto were well-known worldwide for their technical prowess. In the 1950s, one Japanese movie after the other was being shown at film festivals overseas, with most of those productions having been filmed at Daiei Kyoto. Self-indulgently, Daiei nicknamed themselves “Grand Prix Daiei,” and especially the staff who worked for them had an established reputation.

In 1971, however, Daiei declared bankruptcy. Proud to have been called the “most technically proficient studio in the world,” the staff from their Kyoto studios got together to establish a new production company: the Eizo Kyoto Film Company. Nakadai had deep ties with them, and he went on to appear in a great number of their films and TV productions.

I first met art designer Nishioka Yoshinobu, the president of Eizo Kyoto, during the making of Conflagration. Same goes for cameraman Miyagawa Kazuo. The film production folks in Kyoto were true craftsmen. Well, truth be told, actors are craftsmen, too—they both have that artisan’s temperament. That is why we got along so well. Nishioka, for instance, had done a lot of research into ancient buildings and so he could create amazing sets. I’m talking about that sort of artistic skill of a craftsman. The same held true for their filming department, the lighting department, everything. They had that sort of artisan-like, old school mentality that seemed to really fit Kyoto.

I worked on many productions with Nishioka and whenever I walked on his set, it felt like I was genuinely a person from that era. It was sobering. In Onimasa, for example, just stepping into that mansion room with the dirt floor, it really felt like that was what a classical yakuza home would’ve looked like in the early days of the Showa era. That made it easy for me to play the role, too.

Notable Eizo Kyoto productions where Nakadai appeared in a starring role include the two-hour period dramas Yami no Haguruma and Jigoku no Okite, directed by Inoue Akira and aired in Fuji TV’s “Jidaigeki Special” slot in the early 80s. Taking with him to Kyoto some young actors of Mumeijuku—the acting school that Nakadai himself supervises—including Ryu Daisuke, Yakusho Koji, and Masuoka Toru, he handpicked them to appear in the productions alongside him.

Back in those days, I was telling all those youngsters to just hurry up and get themselves to a film studio. “Your acting is no good. You guys need to get to work. You simply don’t have the skill!” I remember being strict in training them. Yakusho, Ryu, Masuoka—people started talking about them because they would show up at the studio even before the security guards. We wouldn’t be able to do what we do without all the staff, so first and foremost I wanted those three to have that consideration for them.

There was the former Daiei veteran director Inoue Akira, and Fuji TV employed this producer called Nomura Youichi. Even when we were working on TV movies they wouldn’t cut any corners, and they would listen to the actors. Through that sharing of opinions, we actually became friends. And I obviously had Mumeijuku and these promising newcomers like Yakusho, Masuoka, and Ryu, so I could just ask them if they could use them in our productions, too.

Mumeijuku was only just in its early stages so there was a lot of enthusiasm. It was a pretty fun time in that regard, too. Director Inoue, Producer Nomura, the staff at Eizo Kyoto… We did some good work together through that sort of communication and teamwork.

Subsequently known as the Kyoto Studio Park, the location with the highest number of period dramas shot in Japan was Toei Studios Kyoto. Nakadai only appeared in a single film produced there: director Sawashima Tadashi’s Three Yakuza (1965). Sawashima is an “entertainment movie” director who took the world by storm with his musicals starring Yorozuya Kinnosuke (later: Nakamura Kinnosuke) and Misora Hibari.

Three Yakuza was an omnibus film that likened the life of a yakuza to the seasons. Kinnosuke played the up-and-coming “spring” yakuza, I did the “autumn” yakuza who had begun to tire of the whole yakuza way of life, and finally Shimura Takashi played the elder “winter” yakuza. I personally really love this film.

I think that film to be Sawashima Tadashi’s greatest masterpiece. I’ve gone out drinking with him since then, and he was never the “picky director” type—he never tried to maintain his authority or anything of the sort. He was just a true film artisan, always laughing. I feel that he could be a very interesting director when he was shooting some form of entertainment.

Toei Kyoto was a film studio with a focus on period dramas, so I believe they had an aversion to actors from a shingeki background. “Oh great, a shingeki guy. Another pain in the ass to deal with.” I got to the studio and there were these actors standing around, some of whom may have been doing small parts for decades, staring me down as I walked in. I said hello and got into the dressing room. I personally loved the Toei period dramas of people like Kataoka Chiezo and I was looking forward to meeting stars like that. Yet, when I walked in there was no one there—everyone had their own separate dressing rooms. I got my make-up done all alone in a dressing room that had been specifically prepared for me, some random actor from Tokyo!

In any case, those small-time actors at Toei Studios Kyoto—they were intense. Walking over to the actors’ assembly hall, they’d be strolling in front of the entrance like they owned the place. I’d have to walk through them to get to my dressing room. That could be a bit scary in the beginning. Well, I did get used to it though. But the first time I went there I was advised not to say I could play mahjong—if you did, you’d soon find yourself constantly surrounded by three others who also did. For women, the similar advice they often got was to never admit they could drink. There was that kind of roughness about the place. But then that roughness was also what made it so much fun.

They were kind to us shingeki actors for the most part, but there was a tradition that you had to tip the actors who you were cutting down—if you didn’t, they wouldn’t die well for you. There were definitely those kinds of traces of the traditional, old school ways present. It was a totally different atmosphere compared to the Tokyo studios of Toho or Shochiku, for example. That atmosphere was like a symbol of the Kyoto period drama scene as a whole.

Toei Kyoto was, in a good sense of the word, an “actors’ world.” The actors would all have five or so assistants—you only had to raise your hand for someone to bring you cigarettes, a lighter, and an ashtray. Back in Tokyo, not even someone like Mifune would have assistants.

“Harakiri”

Nakadai’s first starring role in a period drama was in 1962’s Harakiri. It was filmed at Shochiku Studios Kyoto and it was yet another collaboration between Nakadai and director Kobayashi Masaki, following the six-part The Human Condition.

Nakadai plays masterless samurai “Tsugumo Hanshiro” who begins reciting his past as his full story is gradually revealed. Things that made the film so memorable were Hashimoto Shinobu’s mysterious screenplay as well as the mid-story, sublime scene where Ishihama Akira—playing Nakadai’s son-in-law—performs harakiri using a bamboo sword.

Having finished the four-year filming of The Human Condition, Kobayashi came to me with an offer to make the film Harakiri based on Hashimoto Shinobu’s screenplay.

In the film, I play “Tsugumo Hanshiro” who—sitting on a white tatami mat in the garden of the House of Ii—speaks dispassionately about past events to the man sitting opposite to him, the chief retainer of the clan played by Mikuni Rentaro. Just like it does in Hashimoto’s script, it actually feels more like a radio program than a film. We all used to listen to the radio with all the rokyoku singing, mandan performances, rakugo comedies… That’s what I personally enjoyed doing. It’s that sort of a spoken performance that also forms the basis for Harakiri.

Having come from a stage theater background, I already possessed that knowledge. There weren’t a lot of film actors around at the time who could do that sort of thing, and Kobayashi really made the best of that spoken performance style. His direction, of course, but also the camerawork, the lighting, the casting—it was all perfect. There was Mikuni first of all, Tanba Tetsuro, Iwashita Shima… The actors all had perfect command of the period drama medium. And the sound recording was incredible, too. It being a spoken performance film, it would’ve been all for nothing if it didn’t have great sound.

If I was on my death bed and someone told me I had to pick just one favorite out of all the films I’ve appeared in… While I have appeared in many excellent works, I would ultimately have to pick Harakiri. That is just how perfect everything about it was.

Beginning with Ishihama Akira’s harakiri scene, the entire movie is filled with pain—the kind that women might avert their eyes from. In a word, it’s a revenge tragedy. It’s about a man who has lost everything, taking revenge on society. That cruel harakiri scene symbolizes the absurdity of society as a whole, and showing it thoroughly in all its cruelty is what makes the following revenge scenes so effective. That was Kobayashi’s aim.

The protagonist of this film is a middle-aged man who has just had a grandchild. In playing the character, Nakadai—who was only 29 years old at the time—narrates his dialogue in a very low voice that almost seems to resound from the depths of the earth, giving the role an age-appropriate realism.

I’d always had that “middle-aged air” about me even since I was young. But even so, I of course still put a lot of thought into my preparation for the role. And because I saw Harakiri as a spoken performance film, I paid particular attention to my pitch.

At the time, I was thinking about how I could compete with the best actors of the world; how I could improve, and so I was reading all these books about drama and acting from all over the world. It was then that I came across a biography of UK’s representative actor, Laurence Olivier. It read: “Just like I did with Othello and Hamlet, you have to change the pitch of your voice according to the role.” When Laurence Olivier played Othello, he really did sound like a black man. He was using that unique “Laurence Olivier Low Tone.”

Even in the world of Japanese rokyoku, for instance, Hirosawa Torazo spoke about something called the “Seven Tones of Voice.” I was hooked on all those entertainment radio shows during the war. Rakugo, kodan, naniwabushi… I’d be listening carefully to the radio, savoring the storytelling, so I’d always had that awareness in regards to the techniques of speaking. That speaking skill is important for film actors, too. Before the war, movie stars like Bando Tsumasaburo and Ichikawa Utaemon would, depending on their role, change up their pitch and even their elocution (intonation).

But the thing is that right from about the time I became an actor and entered the world of cinema, and all the way up to today, everyone just speaks in their natural voice when they’re acting. Speaking in your natural voice might give your acting a kind of everyday realism, but acting is… It’s like a cello: you have high tones, low tones, medium tones—you should have ten or so different tones at your disposal.

When you’re playing a role it should be a mix of both truth and falsehood—I believe that’s what the occupation of an actor is. If it was just the truth and that everyday realism, I don’t think the audience would pay money to see it. It’s the falsehood part of it that fascinates the audience. Everyday realism is at the core of a natural acting performance, but as a professional you need to build on that even further.

In Harakiri, to bring out that atmosphere of a middle-aged man who has seen all kinds of battlefields, I used the lowest tone that I possess. In other works, I may use a high or a medium tone. That’s one of the joys of being an actor: using your voice in different ways for different purposes.

When it comes to singers, people are always quick to take issue with all kinds of things in regards to their voice. But with actors, people stopped doing so right around that time. The microphones nowadays are so good that they will pick up anything, no matter how tiny of a whisper it may be. Mics used to be a lot less sensitive and those small ones didn’t even exist yet, so the sound recording folks would just have to try their best to hide mics in places where the cameras wouldn’t capture them. You had to be able to speak loudly and your voice had to carry far enough—otherwise people saw you as being unqualified to be an actor. Moreover, Kobayashi was very particular not only in terms of the picture but the sound as well. He would head out to a Shochiku-run film theater first thing in the morning just to advise them on how to fine-tune the sound.

Afterwards, once we entered the TV era, suddenly none of that no longer mattered. As long as the production had the right “feeling,” spoken lines no longer mattered. That art of talking—something that should be at the core of every professional actor—was deemed no longer essential. And as the producers are getting younger and younger, they seem to have less and less of an awareness as to what actors really are. “Just as long as my next film is a hit, that’s all that matters. I don’t care about the rest.” That’s how their thinking came to be.

And so when I’m talking my students at Mumeijuku for example, I always tell them how they need to use their entire vocal range as actors—high to low—like a musical instrument. Change it according to your role. For me, the lowest tone that I used was on Harakiri. But then on something like Yamamoto Satsuo’s Solar Eclipse, I spoke in a very soft, high voice.

I always alter my vocalization techniques depending on the work. In Yojimbo, I thought about how I should respond to Mifune and that manly voice of his. But then in Sanjuro, I spoke in a lower, harder tone. Those are the sorts of things I would think about. Because actors are like musical instruments.

Argument With Mikuni Rentaro

The majority of Harakiri‘s story advances by way of Nakadai’s monologues. The person in the role of the listener is also the villain: the chief retainer played by Mikuni Rentaro.

Being 10 years older than me, Mikuni is a great senior of mine. He also has a much longer career as a film actor than I, and we actually got into a bit of a dispute during Harakiri.

It started when Mikuni said: “I thought you were going to play it like this, so I’m acting as to respond to that. But you are not playing it like was agreed.” So I retorted: “No, I thought you were going to do it like this, which is why I’m playing it like this.” I suppose I was just being cocky.

Having come from a theater background, I would change the volume of my speaking according to how far the other person was from me—whether it was one, two, or ten meters away. On that set there was a distance of ten meters between me and Mikuni, so I was speaking my lines with that ten-meter distance in mind. But then Mikuni said, “Film acting is different from theater. You have a mic right next to you—you don’t have to speak so loudly.” So I said, “But they can clearly see the distance between us if they do a wide shot. If they do, we need to talk in a way that conveys that sense of distance.” That’s how the argument started.

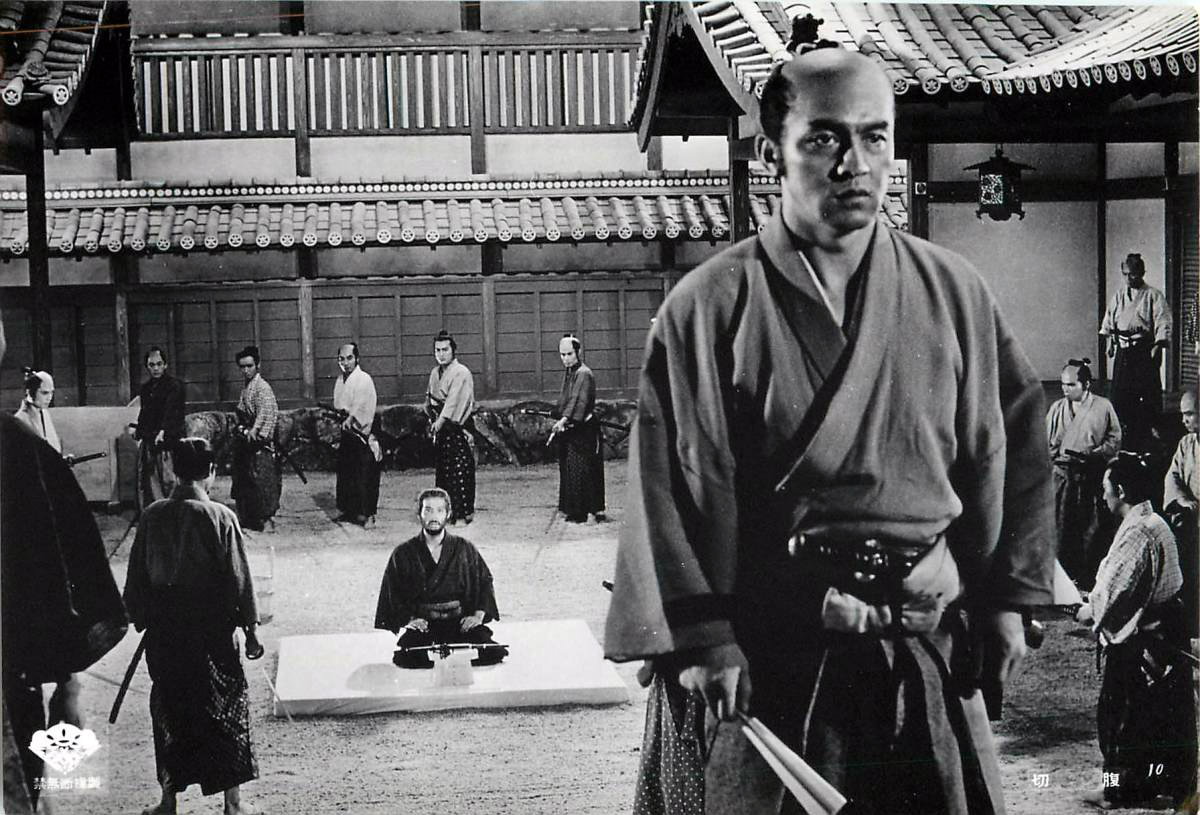

Nakadai and Mikuni Rentaro in “Harakiri”

So Kobayashi then said, “All right. Tell you what. How about you two just take two, three days to talk this out. Hey, guys! Pack up! Let’s go!” He left, taking all the staff with him. It was just me and Mikuni left behind, and we argued and argued until we were both satisfied. Kobayashi, timing his arrival just right, came back and asked, “Are you two good now?”

That just speaks to how much respect everyone had for actors and their acting in those days. Would that kind of flexibility be allowed these days when it comes to making movies, plays, drama? People no longer realize that going through those sorts of “non-essential,” “useless” processes—that is exactly how you produce something great.

Looking back on it now, Mikuni is so great in how “receives” in his acting. I realize now just how lucky I was, having been able to argue with someone of his caliber.

Advice From Kinnosuke

Harakiri ends with a large-scale sword fight scene. This was a source of intense pressure for Nakadai who had not yet learned all the basics of period drama. Giving his support to Nakadai at the time was Yorozuya Kinnosuke (then: Nakamura Kinnosuke). Affiliated with Toei, he was a top star of period drama.

Harakiri was shot at Shochiku Studios Kyoto. Period drama star Kinnosuke was living in Kyoto, and we had a connection because I had acted with his then wife, Arima Ineko, in Black River and The Human Condition, so the two of us were friends. Before we began filming, I invited Kinnosuke out for drinks in Gion and asked him, “Just how does one do a sword fight scene?”

So he said, “Oh, that? You just cut down the people who come at you.” He put it in such a simple way. “Just as long as the guy in the leading role swings his sword well, the people who are getting cut down will do so equally as well. If your breathing matches theirs, the swordplay is a piece of cake.” Hearing him say that, it was such a load off my mind.

He explained how the “fundamental way of cutting someone is like as if you were writing the character for “kome” (“米”).“” First, from your initial stance, you cut upwards diagonally, then immediately after you cut downwards diagonally. Then you cut horizontally, and finally downwards from directly above. He explained that if you picture it as if you were cutting the other person in a “米” shape, that makes it look clean.

At that time, I built a dojo in my yard. While it later became the first training hall for Mumeijuku, back then it was just a training room for me to practice my swordplay. It was in there that I studied the footage of past period drama stars like Bando Tsumasaburo and Kataoka Chiezo—the way that people like them walked, how they acted, how they did swordplay. In addition, I practiced with a wooden sword. Having heard Kinnosuke’s advice I was constantly swinging my sword, trying to learn that technique of the character “米.”

However, me and Kinnosuke did get into a huge fight once. During a break in the filming of Harakiri I visited his Kyoto home. Me, him, and Arima were having a fun time by the three of us until me and Kinnosuke got into a heated conversation about acting theory. “Shingeki is too argumentative.” He said something along those lines, so I said, “Yeah, and kabuki is all formalities.” We got more and more into it, and before long we were throwing whisky at one another. Arima was crying, trying to get us to stop. When we finally made peace, we decided to head out to Gion for more drinks. But once we got back to drinking there, we were right back to fighting again—only this time with our fists. I was filming Harakiri and Kinnosuke was a top star at Toei Kyoto, and yet we both headed to our shoots with swollen faces.

The next morning when I got to Shochiku’s studios, the staff were all worried. “What happened to your face? It’s all swollen!” I explained to them what had happened, and suddenly rather than worrying about me they just asked, “So then… who won?” I said our faces were both equally as swollen—there had been no winner. But they kept going. “Come on now, ‘fess up. You won, didn’t you?!” Apparently, Kinnosuke was asked the same kind of thing at his Toei studio, too. That is the extent to which even the staff of rival film studios were in competition with one another.

Fighting With Real Swords

To take into account safety and emphasize a sense of speed when filming sword fighting scenes, fake swords made of bamboo or duralumin are often used in such scenes. However, Kobayashi Masaki—always a stickler for realism—ignored these conventions in the making of Harakiri.

The sword fights in Harakiri were all performed using real swords. The edges, too, were not dulled—this was Kobayashi’s idea in order to convey how frightening swords truly are.

In the film, I play “Tsugumo Hanshiro” whose son-in-law, played by Ishihama Akira, is forced to commit harakiri using a bamboo sword as per a completely unreasonable order from the clan’s chief retainer, played by Mikuni Rentaro. “Hanshiro,” angered by this, goes on to have a fight at the end of the film. Kobayashi felt that he wanted to capture something that “doesn’t pale even in comparison to the cruelty of a bamboo sword harakiri,” and so he bet everything on us using real swords in that final battle in order to convey “Hanshiro’s” absolute rage.

Real swords were of course also used in my duel scene with Tanba Tetsuro. He told me, “I’m not a crazy person—I’m not going to actually strike at your head.” But even then it was scary. When you’re going for the other person’s torso you can aim it so that you just barely miss them. But when you’re going for the head there is definitely a lot more hesitation, even with a bamboo sword. And this time it was with actual, sharp-edged swords!

Bamboo swords are light, so when you’re aiming at someone’s head you can still use your reflexes to stop yourself before reaching your target. But real swords are heavy—once you swing, there’s no stopping. So when you’re going for someone’s head you just have to aim a little bit off-target. But even then there’s still a person’s life at stake, and that feeling of tension definitely comes across in the picture. I believe that this, too, was Kobayashi’s intention. It was truly frightening.

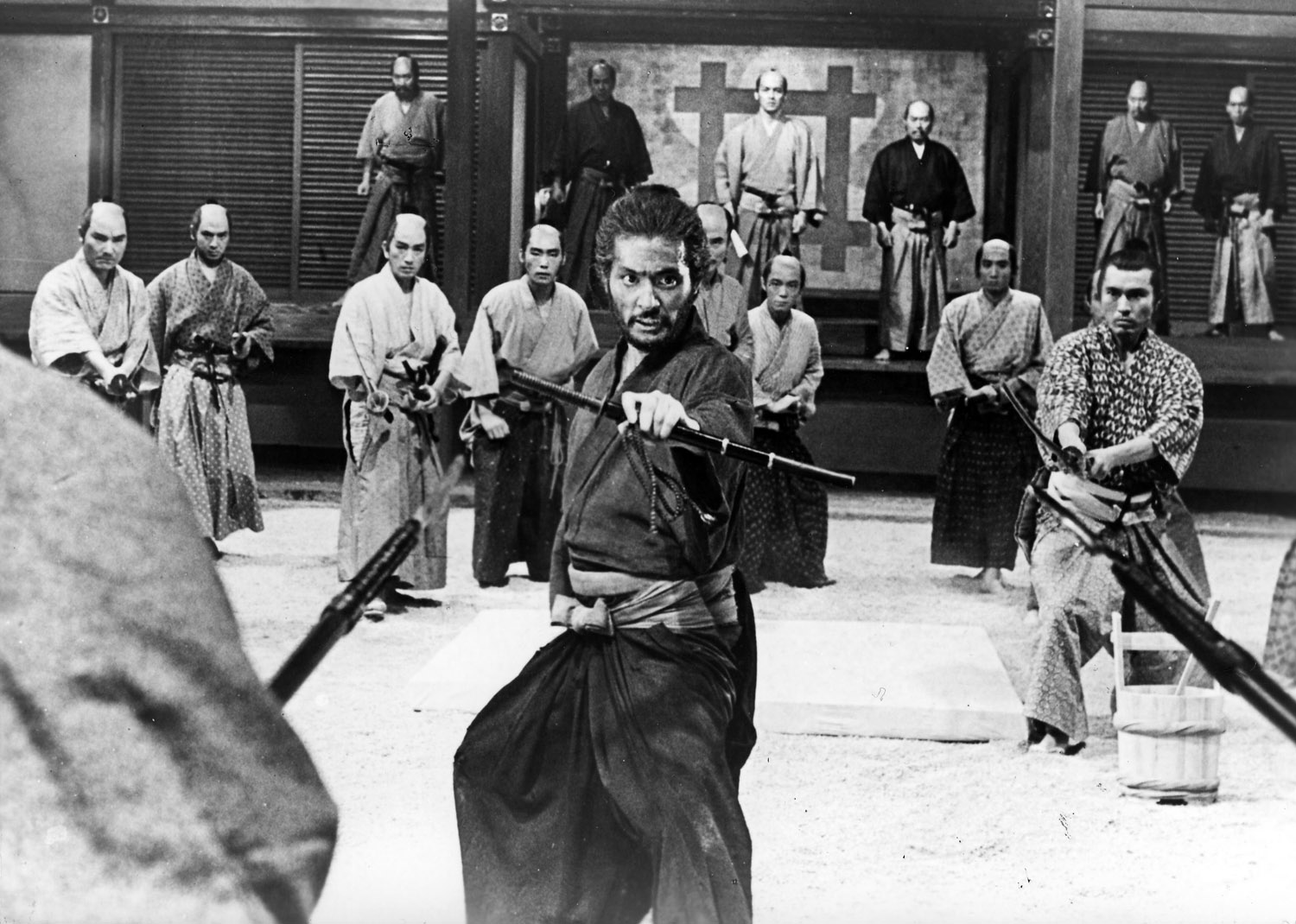

Tanba Tetsuro and Nakadai in “Harakiri”

Behind the camera on Harakiri was “The Emperor,” Miyajima Yoshio, also the cameraman on all six parts of The Human Condition. His unwavering, profound camerawork brings a sense of urgency to the stillness of this brutal story.

Kurosawa Akira was a director who didn’t try to convey his themes to the actors much—this was to avoid the acting becoming too expository. However, if you don’t understand things like the message of the work or the director’s aim, and if you aren’t aware of how the cameras are capturing you and how the lighting is set up, that makes it uninteresting for the actor.

Harakiri was a fun shoot in terms of the camerawork and lighting. Aside from the fight at the end and the reminiscing scenes, I was pretty much sitting down the entire film. Let’s assume it was 10:00 in the morning when I first sat down in that garden of the House of Ii. The film covers that one day, so the time passes to noon and then to evening as I’m just sitting there. They came up with ways to show that passage of time using the cameras and the lighting. Miyajima told me, “After those four years of filming The Human Condition, I’m tired of shooting you! It’s pointless for me to shoot you any more!” But that wasn’t true at all.

For example, between the shots of, say, 10:00 and 11:00, there’s gradually more rays of light visible in that camera angle. As the day turns to evening, there are less and less of those rays of light. That’s the sort of thing they came up with. On first glance it might look like it’s all shot from one angle, but for each and every cut they would adjust the position of the camera and the lights, slightly changing the length and angle of my shadow, or things like the strength of the light or the length of the rays of light. That’s how they conveyed the passage of time. That’s why films are so much fun—but you have to actually spend time on these things to make them so.

Cannes Film Festival

Harakiri was also submitted to the Cannes Film Festival where it won the Special Jury Award.

There was uproar at the screening hall. During the bamboo sword harakiri scene especially, five or six women fainted. There were some yelling, “Horrible!” But then there were people also yelling, “Be quiet!” “This here is an immense film!” So there was dispute like that even during the screening. “Cannes really is something else,” I thought.

After the screening, all the top French newspapers and media outlets immediately reported how “Harakiri is going to win the Grand Prix this year!” Me and the director gave interviews under the assumption that we were going to win—we even did a TV interview on our feelings about having already received the prize. However, the Grand Prix ended up going to an Italian film by Luchino Visconti called The Leopard.

In our prejudice, we started grumbling about how Cannes must surely have given them the prize only to save Italy’s Cinecittá Studios from going under. That’s how much they’d made us believe we were going to win. We’d even made a table reservation at this restaurant where we had planned a celebration. And as it just so happened, sitting at the very next table over from ours were the Leopard people. Director Visconti, Alain Delon—they were all there, happily celebrating. Meanwhile, we were sitting there in total silence… The leader of our party that night, this person from Shochiku’s management, was desperately trying to find some fault with them. “To hell with Italy! Even among the Tripartite Fact they were the first ones to go surrendering to the Allies!”

That’s how frustrated we all felt over our loss. Sure, The Leopard is a terrific film, too—it’s just that we were considered the early favorites for winners of the prize.

On Period Drama

Many of the period dramas where Nakadai appears end with a one-on-one duel scene. His duels with Mifune in Sanjuro and Samurai Rebellion, his duels with Tanba in Harakiri and Goyokin, his duel with Sonny Chiba in Hunter in the Dark… They have always been filled with a breathless air of tension.

The war ended in 1945 when I was in the first grade of junior high school. Accordingly, when I was a child, it felt like running from air-raids was an everyday occurrence for me. One time, I was running away with this relative girl of mine, holding hands. Just when I thought we’d finally gotten away, I looked behind only to see that I was now holding only the girl’s severed arm.

I feel like those sorts of harsh war experiences left a lasting impression on me. I was only a child, but as the air-raids were happening nightly it really was no different than being in a battlefield. Those sorts of views on life and death that were instilled in me when I was a child… “Oh, it looks like I just barely lived today. Tomorrow, who knows. I hope I can live through tomorrow, too.” Even after I’d become an actor, those kinds of things have been at the root of my acting—when I’m fighting in a duel, for instance, I’m sure I’m unconsciously thinking about things like that. “I can no longer resume living if I don’t kill this person.” Those sorts of life-and-death situations.

Nakadai has appeared in a great number of period dramas. As one might expect, he has his distinctive traits when it comes to sword fighting.

I came from a shingeki background and as such I wasn’t brought up on the sword fighting of period dramas unlike actors such as Yorozuya or Katsu Shintaro. That’s something I had a big inferiority complex about, which is why I made my own training hall where I studied for my dear life. But even then I’m just no match for the likes of Mifune, Katsu, or Raizo. I think my fighting style might be most similar to Raizo’s—although with him it’s like he has this single “dance” which is not the case for me. But speaking just in terms of the speed of our swordplay, I think I’m quite close to Raizo.

The actor who could dance in the most beautiful way when it came to their sword fighting would have to be Yorozuya. And then with Mifune, it was the “slash-slash-slash!“—that sense of speed was simply incredible. Meanwhile, Katsu really showed what he was capable of with Zatoichi, and he was just great when it came to the reverberations after he had cut someone. With him, even after he’d cut someone and he was sheathing his sword, he considered the act of doing so to still be a part of the fight, too. That’s what I mean by “reverberations.”

I’m no match to liveliness of Mifune, or the brilliance of Kinnosuke & co. from Kyoto. Instead, I’ve always tried to emphasize the “intervals” in my acting when it comes to sword fighting—not just cutting down recklessly in all directions, but maintaining a tempo.

The fact that I have been able to do so, however, is because I have had skilled actors playing the people I cut down. The timing for when they need to come at you, and the timing for when they need to fall—it’s something that’s the same in all period drama, and if it’s even a tiny bit off it’s ruined. There’s always plenty of roles available for people that need to be cut down, and no matter which film studio you went to they’d always have around five guys who were really good—that is to say, kind of like the faction leaders. But if those guys decided they were going to be mean to you, you just weren’t going have any success there. And that’s why… I hate to say this, but you just had to encourage them with tips. Once you did that, they were happy to die in a pretty way for you—which is what makes the whole scene.

To this day, the fact that even unskilled actors can do sword fighting scenes that are still halfway watchable is all thanks to these people around them who are covering for them. I don’t think it would be an exaggeration for me to say that they are actually the ones who have been sustaining the Japanese period drama scene for all this time.

On another note, I feel like sword fighting is geometrical. For example, say if the camera is directly in front of me… If the person I’m cutting down is front of the camera, or at the back of the shot, then by using that sense of perspective I can strike at them even when there is some distance between us, and to the viewer it will still look as if I’d actually cut them. But when it’s from a diagonal or horizontal angle, I might have to swing at them really close or, in certain cases, even make contact. So taking camera angles into account like that while thinking about the sword fight in a geometrical way is essential.

To that extent, it’s important that both the person doing the cutting and the person being cut are synchronized in their breathing—it’s no good if either one is even a tiny bit too slow or too fast. While this isn’t limited to just sword play, when I look back on the period dramas of those days I’m always struck by how it was those amazing supporting actors who really made it work. Seeing how little there is of that these days… It becomes plain to see just how much the leading actors in those days were being covered by those people.

Following his shingeki beginnings, Nakadai learned on his own accord how period drama is made. Now in the present day when the “film studio system” of the world of cinema has broken down, he feels a strong sense of imparting onto the next generation everything that he himself has mastered.

I’ve been teaching the basics of acting at Mumeijuku for three years. I instruct them to wear a kimono for half the week—the girls, too. I also tell them how their walking should vary depending on their role. In Seven Samurai—my first experience in the world of film—I wasn’t able to properly walk like a warrior. From that experience I learned how a sword is supposed to weigh something—this also means that your waist needs to be that much lower, and then the way you walk will change, too.

That’s how difficult the warrior’s way of walking is. In my youth, I appeared in the role of Miyamoto Musashi in director Inagaki Hiroshi’s film Sasaki Kojiro. When we were doing a scene that was being shot from a low angle, I was told I was no good. “Your gait is too long!” In other words, they were telling me to lower my waist. That just means how important it is to be able to lower your center of gravity. You slide your feet in kabuki, noh, and kyogen, and you learn how to do so in shingeki as well. That way of walking looks appropriate in period drama, and therefore period drama actors need that lower body strength in order to be able to do their job. There’s something athletic about it.

When you think about it, a warrior never knows when his enemy might attack. As a result, he would never be walking around aimlessly or without focus. But when you watch the period dramas on TV nowadays, that’s exactly what they are doing. This just means that the actors no longer have anyone there to teach them otherwise. That is why I want to at least convey that much at Mumeijuku. Setting aside whether or not they can actually do it, I simply feel that I need to convey it to them regardless.

What is going to become of period drama in the future? Yes, I’m sure that the genre itself will be preserved by the new generations. But whether or not they are able of actually creating anything truly intricate? I certainly have the feeling that they have their work cut out for them.

What a pleasure reading these chapters – thank you so much for posting them!

I wish I could read Japanese…Will there be full English translation of the book? I would love to get my hands on a copy!

Hey! Yes, I’m going to translate the book in full. I know it’s been too long since the last one, but I’m going to post the next chapter later this week.

Thanks for reading!

Thank you so much for giving us this beautiful book. It always get me excited whenever I read about Japanese golden age cinema and reading about legendary actor is really refreshing… thanks 😊

Hey Mohammad,

I’m glad you enjoyed the book! It was a magical time in film history indeed.