Kihachi the Buddha

“The Sword of Doom,” “The Age of Assassins,” “Battle of Okinawa”

Okamoto Kihachi was one of the representative Toho directors of the Golden Age of Japanese Film. But while his films cover a wide range of genres, they are a rarity in that whereas the rest of Japan’s cinema had always placed importance on emotion, the majority of his works instead draw influence from American westerns, following a lighthearted tempo.

Many of his films starred Nakadai in a leading role, and the two shared a special friendship.

Meeting “Kihacchan”

Nakadai and Okamoto Kihachi had nicknames for one another: “Kihacchan” and “Moya.” The two first met in 1956. One of them was a fledgling actor, the other an assistant director.

I made my debut in 1956 with the Nikkatsu film Hi no Tori.

The next film I appeared in was the Toho production Hadashi no Seishun. It was directed by Taniguchi Senkichi, husband of Yachigusa Kaoru. There’s this Catholic island called Kuroshima in Nagasaki Prefecture between the islands of Sasebo and Goto. Everyone on the island used to be clandestine Christians, and that was also the film’s setting. Despite having a population of only about 200 they nevertheless had a great, big church there, and we shot the movie entirely on-location. Takarada Akira was the lead, Aoyama Kyoko the heroine, and I played the role of the rival.

Taniguchi’s chief assistant director at the time was Okamoto Kihachi—Kihacchan. Even in his assistant director days he was always wearing black from head to toe like some character in a western. He was very cool. There were quite a few actresses who were infatuated with him back then, always going, “Kihacchan! Kihacchan!”

I believe he worked as an assistant director for 12 or 13 years. He was a most excellent chief AD—even us actors were always friendly with him, calling him “Kihacchan.” He was the intermediary between us—the actors—and the director. But before I knew it, it wasn’t only just an AD-actor relationship between us. We also became very good friends.

He made his directorial debut a few years later with a film called Kekkon no Subete. I was in contact with him at the time. He said to me, “I’m going to be making this film, Kekkon no Subete, starring Yukimura Izumi. I’ve got a role for you—not a very good role, but do you want to do it anyway?” I told him, “For you, Kihacchan? Any time!”

Following his directorial debut, Okamoto Kihachi went on to make films in a variety of genres. Eventually, however, he began to distinguish himself as a director of gangster movies, and his ’59 film Desperado Outpost is what got his name out to the world as just that. At the time when the only thing the Japanese world of cinema was producing were anti-war films, Desperado Outpost was unique in how it was an all out war-adventure-action entertainment film.

Kihacchan was just incredible at making action films. His films from around that time such as The Big Boss—he was so good at making those sorts of pure entertainment films. Toho had really found themselves a treasure in him. But the thing is, working as a director for a mainstream company like Toho and being under their control, he began to feel more and more dissatisfied about that situation.

That was right around the time when I spent four years shooting The Human Condition. Just about that time he made Desperado Outpost, which was the film that really put “Okamoto Kihachi” on the map. He sent me the script and asked me if I wanted to appear in it. But the thing is that while Desperado Outpost is an anti-war film at its core, it was also made in a way that makes fun of the entire concept of war. Meanwhile, I was already taking the anti-war idea head-on in The Human Condition, and while I very much regretted having to turn down his offer I just couldn’t play two completely opposite soldier roles at the same time. We were right in the midst of shooting our own war film… It really was just unfortunate timing.

So I read the script and thought it was very interesting, but I explained to him what the deal was and why I had to turn it down, and Kihacchan totally understood. Ultimately, it ended up being my generation-mate from Haiyuza, Sato Makoto, in the starring role.

“The Sword of Doom”

Nakadai’s first starring role in an Okamoto film was in The Sword of Doom (1966). A period drama, it is a film adaptation based on Nakazato Kaizan’s legendary epic novel. In the film, Nakadai plays protagonist “Tsukue Ryunosuke” who cuts down people indiscriminately.

The Sword of Doom had previously been adapted for Toei by director Uchida Tomu, starring Kataoka Chiezo. Daiei had also made their version starring Ichikawa Raizo. This time around it was Toho producer Fujimoto Sanezumi who approached Kihacchan about producing a version with me in the starring role.

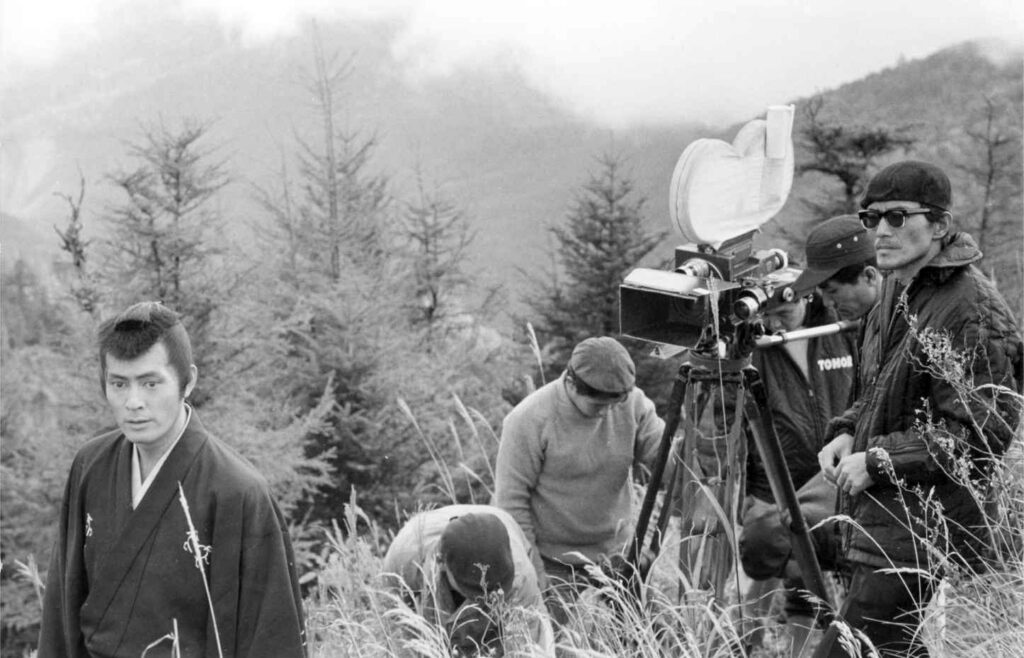

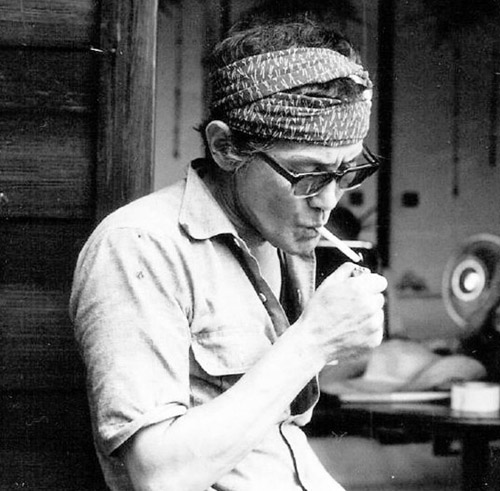

On the set of “The Sword of Doom”

(L-R) Nakadai Tatsuya, director Okamoto Kihachi (far right)

Hashimoto Shinobu’s script, too, was quite something. The original novel begins with the protagonist “Tsukue Ryunosuke” killing an old pilgrim man at Daibosatsu Pass. In the critics’ interpretation of Nakazoto Kaizan’s novel, they felt that his intention had been to write about the Buddhist idea of the cycle of death and rebirth. I believe director Uchida Tomu had shared the same sentiment.

Kihacchan and Hashimoto, on the other hand, felt that “Ryunosuke” was simply murdering people for no special reason at all. No thoughts of Buddhism or anything of the sort—just senseless murder without motive.

I was fascinated by the idea. The critics, however, argued that there had to be a reason behind “Ryunosuke’s” many killings. But in our film there was none to be found, and thus it didn’t get a very good reception in Japan. The image of Uchida Tomu’s previous version was still very prevalent, too. But in America they loved it. At the time they were doing a feature about me at this place called the Japan Society. The Sword of Doom was included in their line-up, and then all of a sudden the people there were super into it—especially the blacks. “There were drugs around even back in those days?!”

The swordplay in that movie was just something else. I spent ten days of filming just cutting down people. I think I maybe ought to have been in the Guinness Book of Records for cutting down that many people! Those last twenty minutes of the movie, I just kept cutting, and cutting, and cutting… I think that was something that went over well overseas.

On certain occasions—such as in this film—there can be seen an intense feeling of madness in Nakadai’s eyes. What does one think about when performing such scenes?

I really don’t even know myself. The only thing I can say about that is, I think about what the director wants from me, about why the script was written, and I think to myself, “what would I do if I was this person?”

People often talk about “getting into character.” But that’s not actually doable. No matter what the role is, even if it’s having to act like you’re completely insane, you can only play it by bringing forth something that is already within you. Let’s say someone was trying to kill you, for instance. No one would just stand there and be still in that situation.

“I wish I could just beat this son of a bitch to death.” Ordinary people have thoughts like these about other people in their day-to-day lives. I simply draw out those feelings of insanity.

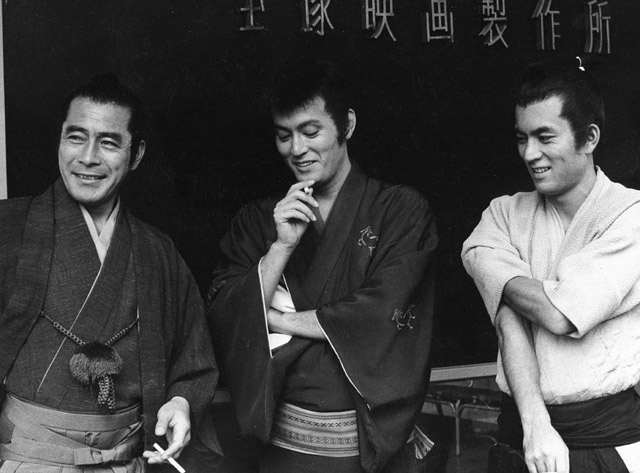

On the set of “The Sword of Doom”

(L-R) Mifune Toshiro, Nakadai Tatsuya, Kayama Yuzo

“The Age of Assassins” and “Moya”

Okamoto’s The Age of Assassins (1967) is a peculiar film. In it, Nakadai plays the protagonist who for some reason or other finds himself the target of a secret society’s assassination plot. However, the protagonist remains unaware of this throughout the story, simply avoiding the assassination attempts as if they were nothing, eventually leading to the society’s destruction. This strange action-adventure still has lots of passionate fans to this day.

At the time, I was doing a lot of roles in the films of directors like Kurosawa Akira and Kobayashi Masaki—that is to say, these colossal works of master directors. But in real life I’m the complete opposite of roles like that. Everyone used to call me “Moya” since I was young, and that’s because I’m totally different from my movie roles—I’m a very absent-minded person. People could never tell what I was thinking. That’s how I got the nickname.

But then one day Kihacchan told me, “I want to do something with you that’s different from Kurosawa and Kobayashi. I want to make something that captures your usual silly sense of humor—your comical side.” That’s how The Age of Assassins came to be. Reading the script, I instantly felt that I wanted to do it.

Us actors, we have to immerse in our roles or else it just doesn’t work. Every new role begins with me trying to figure out what the work is attempting to say, and so I immediately start trying to get a sense for what the director wants of me. For example, I might think, “What would I do if I was someone like “Tsukue Ryunosuke?”” But in the case of The Age of Assassins it was mostly just the real me so there was no need for that sort of role preparation. I found that interesting—I could show a side of me that I hadn’t shown in my previous films. And sure, I also figured the role was something I wouldn’t have to struggle with too much.

The filming itself, however, was difficult. It being a Kihacchan movie, the action was intense. There was this one scene where I was running through a field, fleeing from cannons that were firing at me. They had buried gunpowder in various places on the field and I was to run through it. During rehearsal they had marked those spots with red flags so they would stand out, but then when it was time for the actual take they of course took them all out. So I was just running through one explosion after the other—there was no such thing as CGI back then. Film actors in those days really were something else…

In foreign cinema, they use stand-ins for the majority of that sort of thing. But in Japanese cinema, stand-ins are not allowed. If there’s a small scuffle scene in a western film, for example, and the actor turns his back to the camera even for a second, they’ll use a stand-in for that. They have a proper insurance system overseas, you see.

I was shocked when I appeared in my first Italian western film, called Today We Kill… Tomorrow We Die! You could be a meter away from the camera and if you turned even slightly sideways, they would bring out the stand-in. This is because actors over there are so well-insured that if something was to happen to them, it might bankrupt the whole project. So actors are the most important thing in their film shoots. That’s almost never the case in Japanese cinema—I mean, in The Human Condition I was run over by a tank! What’s more is that anyone who wouldn’t agree to do things like that would be considered a “bad actor.” I’m surprised I’m even still alive!

Despite all this, The Age of Assassins had terrible audience attendance during its premiere. Some theaters had so little viewers they stopped showing it after just three days. Up until that point the executives over at Toho—including the company president—would bow their heads when they greeted me. But once they stopped the screenings and it became Toho’s worst-performing film since its establishment, there was no one there to greet me anymore. Especially since I was just a freelance actor and not an exclusive to them… You have one misfire and suddenly everyone’s giving you the cold shoulder.

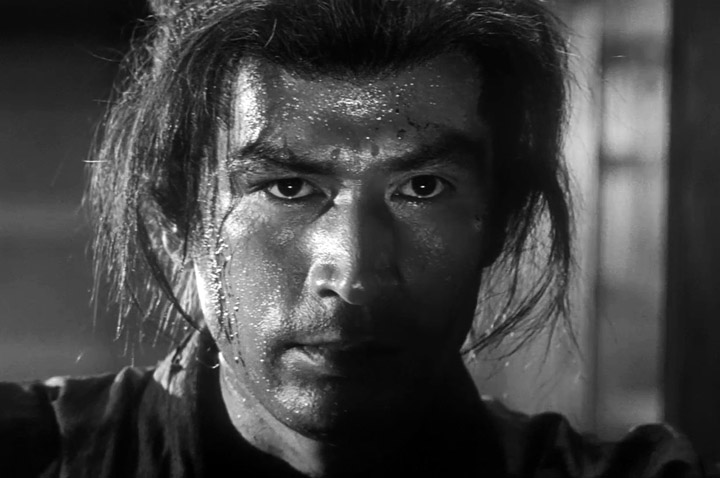

Nakadai in “The Age of Assassins”

In contrast to the norms of Japanese film, the appeal of Okamoto Kihachi’s work is surely found in its speedy, fast-paced direction. Okamoto’s films stand out from those of the other masters of the time who were instead seeking profundity in their work.

I believe him achieving that tempo was all thanks to his reflexes—he had great reflexes. He would himself appear in scenes where he’d be running around all over. His direction when it came to acting was equally as intense. “An enemy spear will come through that sliding screen door, so you’ll go around into the next room as the camera follows you, and…” That kind of thing. Although since I have such a huge, wide body, they couldn’t actually fit all of me on screen.

Also, his blocking was so detailed. Looking at his storyboards it was like reading a flip book. There would be drawings and as you flipped through it, it looked as if the people drawn in them were moving. That’s how detailed it was.

He would have so many transitions that actors new to him would often feel lost. Someone like Kurosawa, on the other hand, would do long, ten-minute takes with four cameras. But Okamoto and his team just weren’t allowed that sort of flexibility—in the Toho director hierarchy, Kurosawa was treated as Rank A and Kihacchan as Rank B. He had no leeway when it came to budgets and scheduling, and so to some extent he almost had to shoot everything fast. But he turned that into an advantage and made his cuts so minutely detailed on purpose, and then he’d just pile those cuts on top of one another in editing. That’s how that distinctive tempo of his—the “Okamoto Rhythm“—came to be.

“Battle of Okinawa”

Kobayashi Keiju & Tanba Tetsuro

At the time, Toho were producing their all-star cast “8/15” series of war films for the Obon holiday season each year. Battle of Okinawa (1971) was one of the films in the series. Having been produced in preparation for the following year’s Okinawa Reversion Agreement, it was a big-budget movie.

We shot that one over a long period of time on-location. While there are other films such as Himeyuri no To that also depict Okinawa during wartime, this was a large-scale film with the Battle of Okinawa really as its central theme. There are American military bases in Okinawa even today, and that is also something Kihacchan wanted to delve into more. I heard rumblings along those lines, anyway.

He himself never saw battle and so he made it to the end of the war alive. Therefore, the war movies of Okamoto Kihachi were always kind of… I don’t know if this is the right word for it, but he was “haunted” by his experience. “If the war had gone on even for just one week longer, I could be dead now.” That feeling was always present in those films. And the feeling was even more pronounced in his self-produced movies, such as The Human Bullet.

The film takes a panoramic approach to showing the final days of Battle of Okinawa in the Pacific War, covering it from the viewpoints of everyone involved, such as the Okinawan islanders and military NCO’s. At the core of the story are three men from the military headquarters: Nakadai, Kobayashi Keiju, and Tanba Tetsuro.

Kobayashi Keiju was the commanding officer at Okinawa, I was a high-ranking officer, and Tanba Tetsuro the chief of staff. It was a so-called “three-lead film.”

Toho’s studios were totally different from their Kyoto counterparts. Filming at Toho would start at 9:00, and that meant it would start exactly at nine. In other words, we would always be there on set by 8:30. While this was true for the Kurosawa team as well, it was the case with Okamoto that if we were starting at 9:00, then you would literally hear “action!” when the clock struck 9:00.

Kobayashi was with Toho and I had appeared in a lot of Toho films, too, so we both knew that the cameras would start rolling at nine o’clock sharp. But Tanba hadn’t worked with Toho a whole lot—he was working mostly out in Kyoto at the time. He was a firm believer in the whole, “the star enters the set last” thing. That is, in fact, how it really was in Kyoto: even if filming was supposed to start at 9, it would often be the case that the biggest stars would only arrive at around 12 or so. A kind of “actors’ tradition,” if you will.

Even when we began filming Battle of Okinawa, it was 10:00 or 11:00 and there was still no sign of Tanba. He finally came in at around noon, all laughing and going, “Oh man, my bad, my bad! I got stuck in traffic!” At first, Kobayashi just laughed it off. But then the same thing happened the next two, three days as well, and each time Tanba would walk in all nonchalantly, just laughing it off.

Finally, Kobayashi told Tanba to come over. Pulling him aside, he gave Tanba a stern talking-to. “Me and Nakadai are showing up on set every day to make it for the nine o’clock start time. This is how Toho does things. What are you thinking, showing up at 10 or 11 or even later?! Just so you know, this is a Toho film—that makes me the most important actor here. And after me, it’s Nakadai. This is your first time at Toho, is it not? This is unacceptable.”

Even then, Tanba just kept laughing it off, going “my bad, my bad!” It never escalated into a fight because of that. That was all Tanba’s charm. But from the next day on, he started coming in on time. There was that sort of comicality about him.

Tanba Tetsuro in “Three Outlaw Samurai”

Like Nakadai, Tanba Tetsuro was not an exclusive actor with any one movie company, and so he appeared in numerous films for each of them. Perhaps for this reason he co-starred with Nakadai in many films where they collided head-on, such as in Gosha Hideo’s The Battle of Port Arthur.

I just love Tanba Tetsuro. He’d often talk to me about the spiritual world—me being his junior, I would listen. He’d always go, “Ahh, you’re no good, Moya. You’re too modern of an actor!” I found him so funny. He was so humorous. He’d often lie, too, because he’s the type of person who was always trying to amuse others. If you called him out on it, he’d go, “wait, how did you know I was lying?!” He was so innocent.

I come from a shingeki theater background, and even when working with Kurosawa at Toho he would always tell me to get rid of my script the moment I walked onto set. As a result, I would have learned my lines perfectly by the time we started filming. But Tanba would always be reading through his script on set between takes, trying to memorize it.

I think it was during the making of Harakiri… He was flipping through his script, and as he did, he explained to me that the way he learned his lines was page-by-page—not scene-by-scene, but literally page-by-page. “There are spirits in the pages,” he’d say. And true enough, once we’d start filming he could indeed recite his lines perfectly. But then this one time he spoke entirely the wrong line all out of the blue. Everyone was puzzled, and Kobayashi yelled out “cut!” He told Tanba he had the wrong line. Tanba replied, “Oh. After reading the first page I must’ve accidentally turned two pages!” No way could this guy have been for real. We were all bursting out laughing.

Also, as far as martial arts was concerned, it wasn’t your typical “movie fighting” with Tanba. He used to do aikido, and so even in holding his sword he was so good at taking a stance.

Every Actor Gets Nervous

Meanwhile, Kobayashi Keiju was one of Toho’s star actors who acted in a wide variety of roles, such as the type of comedy he did with Morishige Hisaya in the hugely successful “Company President Series” but also in films that raised social awareness, such as Kubi and Pressure of Guilt. He, too, starred in many films with Nakadai.

Me and Kobayashi appeared in quite a number of movies together. We did Pressure of Guilt, we did Battle of Okinawa… And while I didn’t get to meet him then, he was in Sanjuro as well.

I got to ask him about many things on set. Not to say we were lazing around back then, but sometimes after a scene we might break for an hour or so as they changed the set. Times like that, Kobayashi would call us young actors over and teach us all kinds of things about acting. He would always perform while appearing to not have a care in the world. I would be as nervous as one can be when I was acting, and I’d watch something like his “Company President Series” and wonder how it’s possible that he never gets nervous—he just has fun and does it.

But then this one time he said to me, “Nakadai, don’t you just hate that actors’ nervousness thing?” I asked what he meant, and he explained it as that strange sense of tingling in the back of your head which one experiences when the director goes “action!“—even if one has heard it hundreds or thousands of times. The “action!” just “hits a nerve,” he explained.

That’s what it is like to be an actor. Even in theater when I’m simply taking that one step from the wings onto the stage, I feel a great amount of nervousness even in that one brief moment. But of course since I’m coming into contact with the audience I try and keep my composure.

When Kobayashi asked me about it, I told him I experienced it all the time. So he said, “Really? Me too!” I was astonished. “Wait, you get it, too?! But it doesn’t come across at all in your acting, like in the Company President Series! You just look like you’re having fun!” He told me that even Morishige experiences it. Everyone gets nervous, and everyone tries not to show it in their acting. Hearing Kobayashi explain this to me, I found myself thinking how strange of an occupation ours is.

The only way to reduce that nervousness is through intense training. To that extent, all the great actors of the past—not just Kobayashi, but everyone from Morishige Hisaya to Mifune Toshiro to Mikuni Rentaro—they were all assertive when it came to their acting and the way they performed. Now, of course, when the director asked them to do something, they would say “yes.” But even while they did say “yes” it’s not like they could do exactly as they were told. They still had to think about how they were going to do it.

Even if it’s Kurosawa telling me to do something and I tell him “yes,” it’s still my body and my spirit that I’m using to perform. There will be some “Nakadai Tatsuya” left in the performance no matter what.

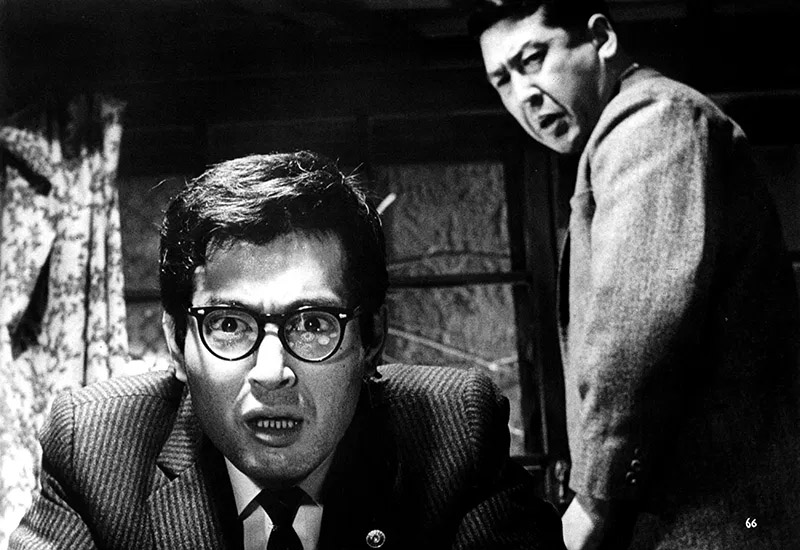

Nakadai and Kobayashi Keiju in “Pressure of Guilt”

Kihachi the Buddha

Instead of emotion, the films of Okamoto Kihachi always exhibited a kind of detachment from their subject, giving them an air of “cool.” It could be said that this made his films feel “un-Japanese” and more akin to the entertainment films of the West.

He was a shy person, never straightforward about his message. Even in his war films he would never just flat-out proclaim, “You are bad! War is bad!” Instead, the message was always somewhat distorted. In war films, he’d accomplish this making fun of it all and turning war into entertainment. And so while the audiences loved his work, the critics did not, and as a result he wasn’t considered one of the “masters.” His more serious, large-scale films like The Sword of Doom and Battle of Okinawa that the company pushed him to do… While he gave those films his all of course, my feeling is that he wasn’t exactly eager to do them.

He would often get into arguments with the company people, never doing as he was told. He was usually always such a nice person, but whenever executives from the company came to the studio, he would disappear off somewhere.

He really was just so shy. For example, if we were filming a sex scene, he would walk off the set. Someone like Gosha Hideo would be right there, wearing his trademark leather jacket and going, “look, this is how you do it,” as he’d embrace the naked actress. Two directors, two extremes. Or if he did stay in the studio, he would be facing away the whole time until the cut. That’s why he never did make even one melodrama film—something about that sort of thing would’ve made him embarrassed. Never straightforward; always steering things towards comedy or action.

Nakadai and Okamoto Kihachi were also good friends in private. Within the film industry circles at the time, this was not commonly seen between a star actor and director.

He was a bit older than me, but even so we used those nicknames for each other: Moya and Kihacchan. Of course, when we were working on a film we would always switch back to that director-actor relationship. But as soon as we were done, Kihacchan would say to me, “I’m the boss when I’m directing. But when we’re drinking it’s you who’s the boss. You taught me all I know about booze.” It’s true that I did teach him a thing or two about booze, as I did about golf. We’d go golfing once a month or so—he even started calling me his “golf instructor.”

As we all got older, me, Kihacchan, and Kurosawa would go golfing quite regularly by the three of us. “Nakadai, let’s ask Okamoto to go golfing with us,” Kurosawa would say. But he was so impatient, Kurosawa was. Just as soon as he’d set the tee, he would already be swinging. And since he was such a big man, the ball would go flying far. But he was terrible with the club—he simply wasn’t very good with all the delicate little maneuvers.

I often used to go to the Okamoto Residence. We would eat, play mahjong, and drink. While his house wasn’t huge, there would always be loads of riffraff hanging about. You’d ask them who they were, and they’d say, “I’m a reporter for the Sports Nippon newspaper.” Or, “I want to be a director but I can’t make a living off it yet so I just come here for food.” Stuff like that. He was looking after all these different people.

Kobayashi Masahiro, the director of my 2010 film Haru’s Journey, was apparently one of those people. I actually don’t remember that period of time very well, but according to him we met there “a whole bunch of times.” Many of those people later became established directors, and Kihacchan—along with his wife—just loved looking after people. It was also filled with actors both known and unknown. The Okamoto Residence was always buzzing. One day, his wife asked him how exactly he managed to feed all those people. His reply was that he sometimes had to rely on the pawn shop to do so.

But the second floor was where Kihacchan’s work room was, and he would never let anyone in there. Even if there was no film in production, he would always be up there writing the scripts he wanted to write. He kept writing up there right until around a week before his death.

All of which is to say, my relationship with Kihacchan felt somewhat different from people like Kurosawa Akira or Ichikawa Kon. He was a friend. When we were on set he never told me off on my acting. If Kobayashi Masaki was “Kobayashi the Demon,” then Kihacchan was “Kihachi the Buddha.”

Okamoto Kihachi

Unfortunate Final Years

Many film directors will have a project they have been silently working on for a long period of time, but their passing prevents them from ever getting to make said project into a reality. Okamoto Kihachi was one of those directors.

The final thing Kihacchan wanted to do was Yamada Futaro’s Gento Tsujibasha. He’d even finished writing the script for it. It’s about this old Aizu man who was on the losing side in the Boshin War. He leaves for Edo on his horse carriage along with his grandchild, and there they meet a child who had died in the war. It was a very fantastical, interesting script. He had told me how eager he was to start filming it… but that is when he collapsed. Vengeance for Sale was the last film he made, but he really was going to start on Gento Tsujibasha after that one.

In his films, Okamoto Kihachi would always feature his regular cast of actors as the villains: Kishida Shin, Takahashi Etsushi, Amamoto Hideyo, and Sunazuka Hideo. The fans called this group the “Kihachi Family.”

People like Amamoto Hideyo—my senior at Haiyuza who would often treat me to meals—and Sunazuka Hideo—who had a background in comedy—would often appear in Kihacchan’s films. He would regularly give out parts to those kinds of actors who usually only got to play small parts… Yet another reason why he was “Kihachi the Buddha.” The thing is though that if you were to ask the staff, they’d all say he was the most relentless director of them all. But he was always kind to us actors.

Back then, the directors would all have their own “family.” Not just Kihacchan, but Kurosawa, Kobayashi… everyone. After the same staff and cast had worked together for years and years on end, just a couple of words was all it took to get the message across which meant that everything on set proceeded smoothly. Of course, because there are only so many truly outstanding staff and actors out there, I’m sure the directors all wanted to acquire all the talent of that caliber for themselves.

Now, as the leader of his own acting troupe, Nakadai says the time he spent with Okamoto Kihachi has been of great help to him.

I believe Kihacchan was always observing the actors. Even though we’d see each other often, he would watch me when we were just hanging around doing nothing and he’d think, “what kind of an actor is Nakadai Tatsuya?”

Now that I am myself running Mumeijuku, I will of course watch our rehearsals and the like, but even more than that I’m watching my students in everyday situations. I’m observing them and trying to find the good in them as actors, as I assume that’s what they want to make it as. When it comes to acting, they can always work on their weak points later. Doubling down on their strong points—that’s where I want to start.

Great work as always !