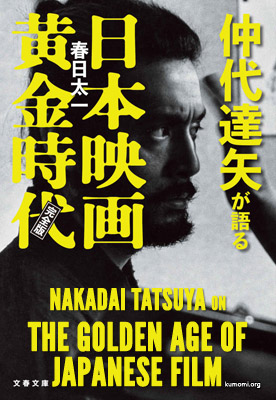

Gosha Hideo and the Passion of Great Actors

“Goyokin,” “Hitokiri,” “Hunter in the Dark,” “Onimasa”

While today there are numerous film directors who got their start in TV, when television had first just emerged (TV broadcasts began in 1953), people thought little of it in the 50s and 60s—the Golden Age of Japanese Film. Film directors like that used to be rare, but the man who first paved the way through those uncharted roads was Fuji TV’s Gosha Hideo. He would later go on to use Nakadai in many of his films in leading roles. For Nakadai and Gosha both, they each hold an essential position in their respective filmographies.

In this chapter, we asked Nakadai about his memories with Gosha Hideo.

“I Need Those Crazy Eyes of Yours!”

Originally a director for Fuji TV, Gosha Hideo first got his name out there with the 1960s TV series Three Outlaw Samurai. Gosha made the series into a huge hit by developing the sound effects of his sword fights, giving them the sort of realistic intensity one might expect from a Kurosawa movie, even when viewed on a tiny TV screen. With the film adaptation of Three Outlaw Samurai the following year, he became the first TV director to break into the world of film. Afterwards, he kept busy directing both movies as well as TV programs.

Coming from a TV background, Gosha’s style as a director was to always prioritize the entertainment value of his works—even if it sometimes meant destroying the entire theme of the work in order to incorporate action scenes, depictions of violence, or sexuality. As a result, he faced severe criticism from film critics at the time, and even today he is not often talked about in terms of film history. But by the same token, he was very much trusted by film producers as he was constantly making big-budget entertainment films to great acclaim from waves of moviegoers.

Nakadai’s first performance in a Gosha film was in 1966’s Cash Calls Hell.

Directors like Kobayashi Masaki and Kurosawa Akira were older than me, and so I saw them almost as these “father figures.” In contrast, there were other directors who I thought more of as my “big brothers”—directors to whom I could say anything since we were close in age; directors with whom we would make films through constant back-and-forth discussion. To me, those directors were Gosha Hideo and Okamoto Kihachi.

My first film with Gosha was Cash Calls Hell. “Wow, for being only a TV director, this guy sure keeps just as busy on set as any other director I’ve seen.” That was my first impression of him. Our collaboration began with Cash Calls Hell, and from thereon I always stuck by him.

In describing me, Gosha apparently told someone, “That guy, he has madness in his eyes.” I heard of this and I told him that I was certainly not a crazy person. But then he said, “No, it’s not that you are. But your eyes—they’re totally crazy! And in order to portray my protagonists, I have to have those eyes.”

The Sublime Cinematography of “Goyokin”

The next film that the two collaborated on was 1969’s Goyokin. This movie marked Fuji TV’s initial entry to film production, and with the aid of a plentiful budget, this blockbuster of a film featured an extravagant cast including Nakadai in the leading role, Yorozuya Kinnosuke (then Nakamura Kinnosuke), Tanba Tetsuro, Asaoka Ruriko, and Tsukasa Yoko. With this work, Gosha did something that was unusual in period drama films of the time: action scenes in entirely snow-covered areas.

The majority of Goyokin was shot at the Shimokita Peninsula. It felt like -30°C or so, there was an incredible amount of snow, and the shoreline was full of cliffs.

The scariest thing to film was that scene near the end where I’m climbing up a cliff. With the ocean right below me, there were these tremendous waves that came crashing towards me. The cameraman, Okazaki Kozo, had his camera pointed directly at me from above, and I was to climb up the cliff towards him.

So then Gosha says, “I want the shot of you to also include the sea spray hitting against the rocks below.” That meant there was nothing we could hide from the camera—I would have to climb with no safety rope, no nothing. So I told him, “Hey, listen. If I slip and fall from there, I’m a dead man.” Gosha just said, “Here, let me show you,” and he actually climbed up the cliff himself, still wearing his leather boots and jacket. Seeing that, I obviously had no option but to do it myself.

Also, Gosha was someone who would personally plan out even the finer details of fight scenes. In the climax, we fought on the coast in -30°C weather—and not on a sandy beach, bear in mind, but this unsteady, rocky area. In the end when we got into the ocean for more swordplay, the ocean water was actually warmer than the air.

The film ends with a duel between me and Tanba Tetsuro. This, too, was filmed in a huge blanket of snow. Tanba shows up with a torch, holding his hand to it as he confronts me. On the other side, I’m warming my hand with my breath. And like that, little by little, we close the distance between us. This, too, was all the director’s idea—after all, one wouldn’t be able to just hold a sword like it was nothing in freezing -30°C weather.

Finally, we cross swords in the snow and we both fall over, blood spurting out as the snow all around us is dyed in red… Until I rise, victorious.

Gosha was so good at coming up with that sort of thing.

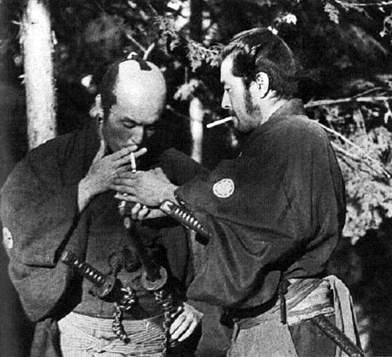

Nakadai and Tanba Tetsuro in “Goyokin”

After Goyokin, we did a film called The Wolves where I play a yakuza character. Here, I did fight scenes with a knife. Swords are longer which means that you still get to maintain some amount of distance from the other person when fighting them, but with the knife and its short blade, you have to slam into people with your whole body. You have to be willing to get at least somewhat hurt and there is even a possibility of death, so this was again something different from your average swordplay scene.

Gosha’s direction style was, shall we say, heavily reliant on special effects. He was a director who always wanted to show off as much as possible. There are directors who want to show off, and then there are directors just who want to portray everyday realism in a silent way. But thinking about it in terms of “truth” and “falsehood,” for me it’s the movies where both come together that are the most interesting. For me, personally, I don’t particularly enjoy films where there’s zero showing off.

In that sense, Gosha resembles Kurosawa. At the end of Sanjuro when Mifune Toshiro cuts me and the blood starts just shooting out, when Gosha saw that scene, he apparently thought, “…He’s got me beat!” But, never being one to back down, he then went on to try all kinds of ideas to try and outdo Kurosawa. For example, in the Fuji TV version of Three Outlaw Samurai, he apparently came up with this idea of creating a life-sized person out of film, and then he quickly tore it open from the shoulder and had blood start spurting out from the resulting tear.

Kurosawa was similarly conscious of what Gosha was doing. One time he asked me, “Hey Nakadai. You appear in a lot of Gosha’s stuff, right?” I told him that I did indeed, and that he was a friend. So then Kurosawa said, “Tell him to stop copying the way I make my movies.” He felt that Gosha was copying him, and quite shamelessly at that. I explained to him that Gosha was only copying him purely out of respect. He replied, “Well, I still don’t want to be copied.” I finally managed to convince him by explaining how even the great people of the past, like Zeami Motokiyo, used to say that copying and mimicking someone was the same as studying them. Kurosawa just said, “Oh…?”

But the director who Gosha respected the most was Kobayashi Masaki. Whenever I was working with him and it felt like filming was taking rather long by Gosha’s standards, it was always because he was trying to copy Kobayashi. The thing about Kobayashi is… I guess it was a strength of his that he could maintain the quality of his films even when they had long running times. With Gosha, there were times when I wasn’t sure if some of his films needed to be as long as they were. But my feeling is that Gosha wanted to make films like Kobayashi’s, although this is obviously just conjecture on my part. In any case, the two were very friendly with each other. Believe it or not, they were actually mahjong buddies.

You know, I’ll sometimes try imagining a movie made by three people: Gosha Hideo directing the opening, Kobayashi Masaki directing the middle, and Okamoto Kihachi directing the ending. Three directors, one film—I bet it’d be a lot of fun. Gosha is great at directing openings. Then the middle… We’ll call it the “drama part.” Kobayashi would push it along with care. Finally, Okamoto would finish it with a sense of urgency—bang! Although I suppose Okamoto could just as well do the opening. Anyway, it’s something I think about sometimes.

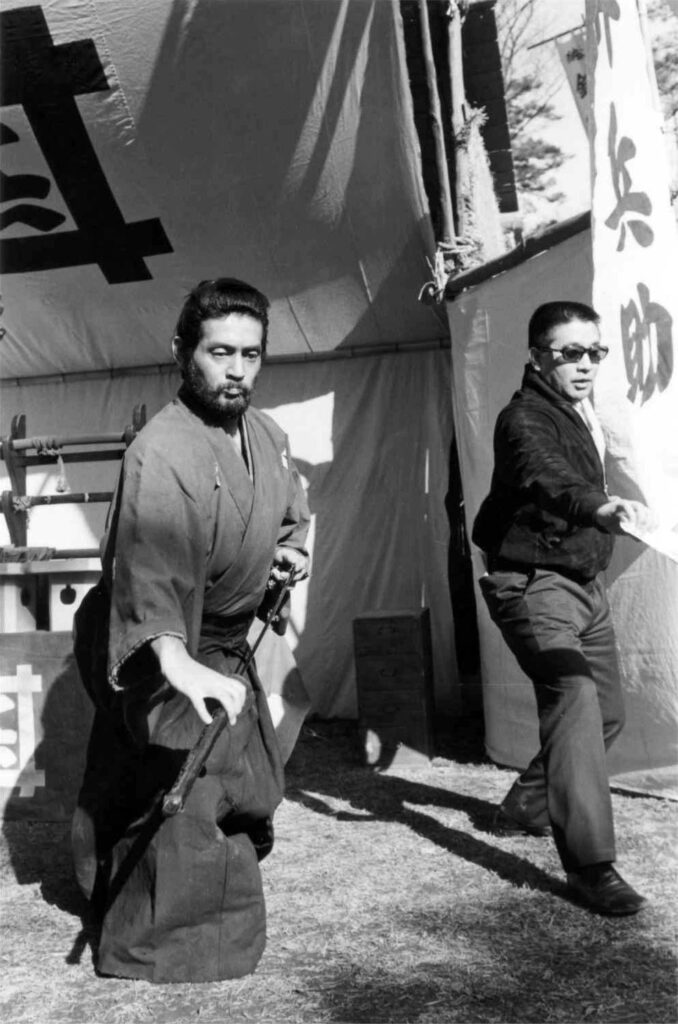

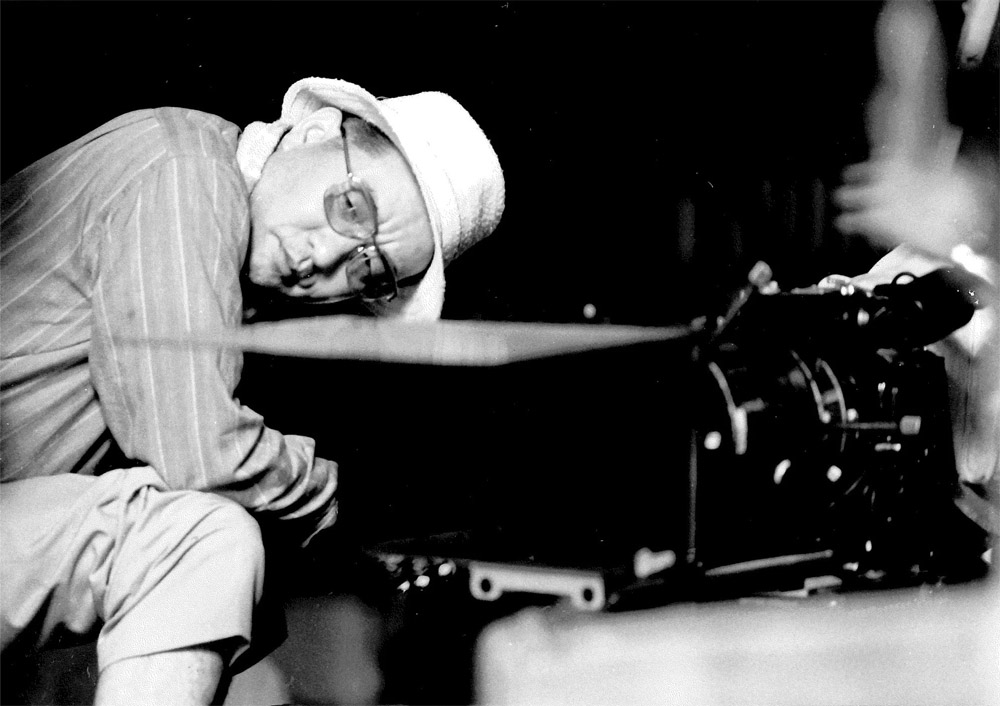

Gosha Hideo (R), giving Nakadai some hands-on fencing instruction

Mifune Out; Kinnosuke In

Goyokin tells the story of a ronin, played by Nakadai, once affiliated with a northern feudal domain where a shipwreck incident has occurred. Attempting to resolve the issue with him is a mysterious samurai, played by Kinnosuke. However, his role was originally meant for a different movie star altogether.

We made a very good film with that one, but there was a certain incident that occurred during its filming. While Yorozuya Kinnosuke played opposite to me in the film, his role was originally meant for Mifune.

“I’ve killed you in so many films, so this time it’s my turn to be your supporting man!” He meant to do the role in part to show his gratitude to me, and when we were shooting on-location at the Shimokita Peninsula, we’d be at the hotel drinking together every night after filming.

But the thing is… The thing about Mifune is that while he was usually a very good-natured and thoughtful person, he could get a bit out of control after some drinks. So then one night he just lost his temper, although I’m sure I wasn’t totally without blame either. Anyway, we got into a big, heated argument. It turned into this tit-for-tat thing. “To hell with this movie! I will not do this project!” “That’s fine, just step down then!” And that is exactly what he did before taking a long-distance train back home from the Shimokita Peninsula.

By that point they had already shot quite a lot of material with Mifune. I immediately phoned Fujimoto Sanezumi, a producer for Toho at the time, to explain what had happened and to tell him how sorry I was. Naturally, I also apologized to the director. Gosha said it wasn’t my fault, and Fujimoto too assured me that we’d find a replacement. But we’d already spent over half a month filming over there in the snow of Shimokita Peninsula, and now it was all going to go to waste. It would’ve been totally within the realm of possibility if the entire film had been cancelled because of this incident.

So I called my wife at home. “I have to pay reparations! I don’t care what you do to get us some money! Sell off our land if you have to!” Not that we owned any land to sell off to begin with, mind you. I then called Kinnosuke who I was good friends with, and he just said: “Right then, guess I’m heading over!” And so he came to Shimokita Peninsula right away, and somehow everything worked out in the end all thanks to him. Me and Kinnosuke shared a very lighthearted relationship, so he accepted to be Mifune’s stand-in for Goyokin like it was nothing. He really came through for me that time.

The media had a field day with it, too. The most symbolic thing came about because at the time we were doing commercials for these vitamin drinks—Mifune for Arinamin and me for Poporon S. So then the next morning’s newspaper headline read: “ARINAMIN VS. POPORON!”

Afterwards—and this makes us sound like we’re yakuza or something—Kurosawa made the arrangements for us two to meet at a ryotei restaurant out in Akasaka. That is where me and Mifune ceremoniously shook hands and made peace.

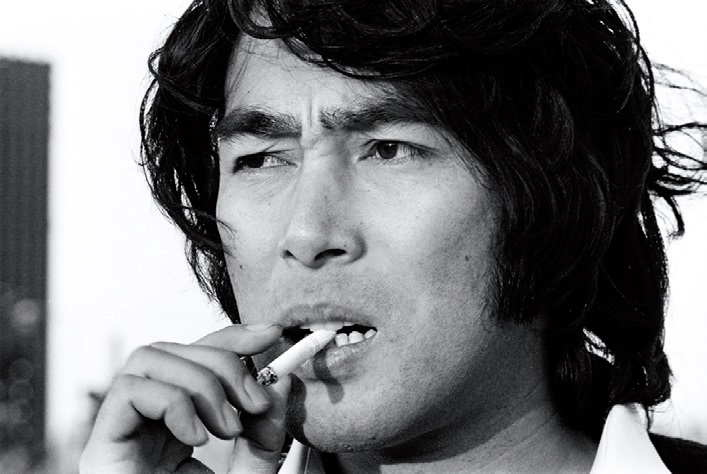

Nakadai and Mifune Toshiro

“Hitokiri”

Katsu Shintaro & Mishima Yukio

In 1969, in addition to Goyokin, Nakadai also appeared in Gosha’s Hitokiri. This film was a co-production between Fuji TV and Katsu Productions, a company established by Katsu Shintaro, a Daiei top star equaling Raizo. Its story is set at the end of the Tokugawa shogunate, with a group of ronin—the “hitokiri“—engaged in a bloody, terroristic feud.

Fully loaded with action, it is very much an entertainment film. But it was the movie’s lavish cast which attracted the public’s attention. Playing the part of the lead hitokiri “Okada Izo” is Katsu Shintaro, while “Takechi Hanpeita” played by Nakadai Tatsuya is pulling the strings in the background. “Sakamoto Ryoma” is played by Ishihara Yujiro, and the hitokiri from Satsuma, “Tanaka Shinbei,” is played by master writer, Mishima Yukio.

The great author, Mishima Yukio, gave his all to that role of “Tanaka Shinbei.” He’d become a real, professional actor. With Gosha being there as well, no one treated him like a writer. Every night after we were done filming, Katsu would take me, Yujiro, and Mishima drinking out in Gion, and Mishima would always be asking us for acting advice. “How do I act in a situation like this?”

Mishima’s character in the film commits seppuku. Mishima had the most amazing physique at the time—he was a bodybuilder, you see. So one time I asked him, “Hey Mishima, how come you’re working out so much even though you’re a writer? You look like a proper actor!” He told me, “When I die, I’m going to do so by seppuku. And when I do, it would go against my sense of aesthetics if any fat was to come pouring out of my abs. So I do it to get rid of the fat.” I said, “Come on, Mishima. Stop joking around!”

It was maybe a year later when the you-know-what incident took place at the Ichigaya JSDF station where he truly did commit seppuku. I had shivers running down my spine as I thought to myself, “He really meant what he was saying to me that time.”

The highlight of Hitokiri is the clash of two extremes: Katsu’s wild performance as the illiterate, vulgar “Izo,” and Nakadai’s performance as the resourceful, clever “Takechi.”

The role of “Takechi Hanpeita” was modeled after the play Tsukigata Hanpeita—this handsome sort of character who would suggest to a geisha that they “go and get ourselves wet out there in the spring rain,” as he steps out for a walk in the night streets. In his screenplay, Hashimoto Shinobu took that image of the character and made it into this almost politician-like “Takechi Hanpeita.” So I played this extremely cold-blooded man, while Katsu played this very brutish, instinctive type of man. That difference between the two characters is what made it interesting.

Me and Katsu had no discussions prior to the filming in regards to our acting in the movie, and Gosha gave us no instructions either. Gosha was one of those directors who would just say, “Play it however you like.”

Not only were our roles clashing against one another, but even as actors me and Katsu were… competing, I guess you could say. To make that film work, we both had to fully understand our roles when we came to blows. That’s what makes it intriguing. “If you’re going to do that, then I’ll do this!” That’s how the fights were.

But the trouble was that we were struggling to reach agreement as to how to do things. Just as it was when I co-starred with people like Raizo or Yorozuya Kinnosuke, when the other person comes from a traditional performance arts background and then there’s me with my shingeki background, it leads to mutual feelings of rivalry. As a result, there would be constant debate in regards to acting theory at the film studio.

We actors tend to be on the serious side. Someone like Yujiro would come on set and go up to the script supervisor, saying, “I’m so hungover. I had too much to drink last night. What was my line again?” But it was all lies. In reality, he’d been studying his lines for days. He knew them by heart. Same thing with Katsu. He’d say, “I can’t memorize my lines in advance. I have to just say them in the moment.” But when you see his acting, it sure doesn’t seem like that’s what he’s really doing.

One time I even told him as such. “Yeah, yeah, say that all you like. Just admit it: you know full well what we’re doing next.” Actors back then would claim they never did any preparation for their roles, but the reality of it is that we all did. Everyone had this sentiment of studying somehow being “uncool.”

Mishima Yukio, Ishihara Yujiro, Katsu Shintaro, and Nakadai Tatsuya in “Hitokiri”

Ando Noboru & Ishihara Yujiro

The yakuza epic The Wolves (1971) saw the reunion of the Goyokin line-up of Gosha/Nakadai/Okazaki (camera). Playing opposite to Nakadai in this film was Ando Noboru. As the real-life boss of the Ando-gumi yakuza organization, he made the entirety of Shibuya into his gang’s turf right after the war. Later, in the aftermath of the Yokoi Hideki Shooting Incident, he served time in prison and dissolved the group, after which he quit the underworld and became an actor.

Ando Noboru was very interesting as an actor. I was merely playing a yakuza character, when meanwhile you had here someone who really had been a yakuza himself.

But there was this one thing that happened which made me think, “Huh, I guess the yakuza folks have it hard, too.” Whenever we’d get off the train at our filming location, there would be a line of all the local yakuza there at the station, waiting to pay their respects to Ando. No matter how small the town, there’d always be a group of yakuza waiting for us.

Ando, not liking this, would apologize to me and graciously ask me to get off the train before him. In any case, it was like that no matter where we went. Once we finished making the film, we still had to go around promoting it in theaters in various places, and even then—whether it was Osaka, Kyoto, you name it—there’d always be 20 or so yakuza members waiting for us. Each time, Ando would bow his head and apologize to me profusely.

As an actor, he was incredible even when he was just standing there. He’d say, “Nakadai, I’m no an actor. Please teach me all you can.” But for me, I was only thinking about how amazing it was to watch the “real deal.” He wasn’t doing anything in his acting to come across as a yakuza per se, and yet he was just so… intense. I’m sure he’d had all the real-life experiences in his past, shooting at people or having to pull out a knife and all that, but that was now all silently locked up inside him. There was just this sort of a quiet intensity about him.

He’d often say to me, “I’m no actor.” Hearing him say that, I thought to myself… “Hmm. I’m sure I remember someone else telling me the same thing in the past.” I then remembered who it was that I was thinking of: Ishihara Yujiro.

Yujiro made his debut in A Slope in the Sun, right around the time I also made my film debut with Hi no Tori, similarly for Nikkatsu. We shared the same dressing room and we got to talk quite a bit. One time I asked him, “So Yujiro, I hear you’re still a student. Aren’t you going to try and become a full-time actor?” He said, “Mmm… Well, no. Acting isn’t a man’s business.” He wasn’t particularly aiming to become successful at it.

So hearing Ando say what he did, it made me think how the two resembled each other in that sense. Me, I’d spent three years at the training school being told all kinds of things about acting during my time there, so I’d get nervous when it was time to act for real. But not those two—they never even wanted to be actors in the first place! They could just be themselves.

Gosha Hideo is an Italian

One characteristic of Gosha’s films was how the stories could at times be difficult to comprehend, and yet each time one left the movie theater after having seen one of his works, there was always a feeling of contentment; a sense of having seen a good movie. The Wolves was one such movie.

The Wolves begins with a sex scene between me and Enami Kyoko. These two loners happen to meet at some deserted inn somewhere in the Shimokita Peninsula, and the moment they do they embrace as they both try to forget about their sorrows. And then, after they part, they never meet again. That’s the kind of thing that would make people who don’t like Gosha say, “That doesn’t make any sense!” True, if you’re only thinking about it logically, it doesn’t make sense for these two people to do that.

Reading the scripts to Gosha’s films, I would often come across things that didn’t make logical sense. So I’d ask him. “Hey Gosha, I don’t get it. What is my connection to this woman?” He would tell me, “Don’t worry about it. It’s just the way people are.”

The way he conveyed these inexplicable things about the human nature was not through logic, but through images. Some forlorn inn in some corner of the Shimokita Peninsula… Or some abandoned boat… He would portray emotions using imagery like that, going beyond mere logic. He was very, very good at creating that sort of imagery.

I once told Gosha: “You’re like an Italian!” What I meant by that is, even if you told him you didn’t get what was happening in certain parts of the script, he would tell you not to worry about it because he would show it in pictures instead. “The audience will get it,” he’d say. That was quite Italian of him, I felt. See, Italian films can have that quality about them where you don’t quite get the point, and yet you keep watching because they’re still interesting regardless. There was a similar sort of… “picturesque” aspect to his films.

Gosha was able to accomplish this because he had brilliant cameramen who could shoot his imagery exactly the way he wanted. Okazaki Kozo shot Goyokin and The Wolves, while Morita Fujio shot Hitokiri and Onimasa. They could shoot the images that Gosha wanted, creating worlds full of color.

Nakadai’s hand and Enami Kyoko in “The Wolves”

Directing Sex Scenes

As with Enami Kyoko in The Wolves, numerous other actresses have also appeared in daring nude scenes in Gosha’s films, performing in passionate sex scenes. Nakadai has acted alongside many of said actresses in those types of scenes.

Gosha was very particular about fight scenes, but he was even more enthusiastic about the sex scenes. Action and eroticism—those were the two major themes for him. And so, indeed, he would get his actresses quite nude. I suppose the actresses felt that it was something par for the course when it was a Gosha movie. They’d probably read the script and think to themselves, “Ahh, looks like I’m going to be getting naked again.”

Now, I get embarrassed so I’m not a big fan of doing sex scenes. I’d ask the director. “What do you want me to do in this scene?” So then Gosha, he would step in and demonstrate together with the actress. Still wearing his leather jacket, he would sometimes be on top, sometimes under the actress, all while explaining it to me. “Can you do it like this, Moya? Then move like this, and we’ll have the camera follow you.” I received quite a lot of acting guidance like that from him. I did feel sorry for the actresses though, having to be embraced by this guy in his leather jacket…

“Hunter in the Dark” & Harada Yoshio

The Gosha-Nakadai duo also worked together on the ’78 Shochiku film Bandits vs. Samurai Squadron. This bandit story is based on a historical novel of the same name written by Ikenami Shotaro.

The interesting thing about that one was how in the novel the bandit Kumokiri Nizaemon—played by me in the film—hardly ever makes himself seen. But in our version, as it was a film, he had to do so. That aspect of it was difficult. See, he has placed his subordinates all over and he needs to manage them, so he’s someone who shouldn’t really be seen out in public. But again, as it was a movie, we couldn’t do it that way. There was no way around it. He had to be there. And as it was a Gosha film, there were of course the sexual scenes as well, making it that much more difficult.

After the success of Bandits vs. Samurai Squadron, the following year the two adapted another Ikenami Shotaro novel: Hunter in the Dark. Based in the underworld of the Edo period, the novel depicts the struggles amongst an organization of professional hitmen. However, Gosha only used the basic premise of the novel, completely disregarding the aspects of the original work emphasizing emotions, instead making the story into a conflict drama filled with violence.

One day I was reading this serialization in a newspaper—I forget now which one—and I was taken with the title of it. I spoke about it to Haiyuza producer Sato Masayuki who had also taken part in the planning of Bandits vs. Samurai Squadron, and the subject then made it to Gosha. After reading it, he then decided to use it as material for Hunter in the Dark. But that’s really all it was supposed to be—just additional material. But then the film ended up becoming something completely different from the novel, and Ikenami obviously wasn’t pleased.

The movie ends with a duel inside a chicken coop between me and Sonny Chiba. Again, Gosha really was good at coming up with that kind of thing. That was neither in the script or in the original story.

We shot that movie in Gotenba, and there was a scene where they were going to film us from the air in a helicopter. But then it just so happened that the Costume Department had forgotten to bring our costumes, so then they actually took the helicopter that was supposed to be used for filming and flew it to Tokyo to retrieve the costumes. See, around this point in time everyone was kind of just starting to… slack off, I feel like. The film industry was in decline. And so was I. Good scripts were still coming, but for some reason or other I just wasn’t feeling it, and so I kept myself busy playing golf. That was the sort of time it was for me.

In Hunter in the Dark, Nakadai plays the manager of an organization of professional killers. But in this film, it was Harada Yoshio who left an especially strong impression playing Nakadai’s bodyguard, a swordsman suffering from amnesia.

A junior of mine at the Haiyuza Training School, Harada was a very good actor who has now unfortunately passed away. He was eight years younger than me. His generation-mates included the likes of Natsuyagi Isao and Kurihara Komaki—the “Glorious 15th Generation” as they called them. Hira Mikijiro was one generation my junior while Tanaka Kunie and Igawa Hisashi were two generations below Hira, so all in all Harada was over 10 years below me in terms of the training school generations.

I was doing theater and film concurrently, and thus many of the young people who joined afterwards tried to be like me—even if it is strange for me to say so myself. When Yamazaki Tsutomu made his debut, people were calling him “Nakadai II.” That just kept going with each new face. “Nakadai III.” “Nakadai IV.” I forget now what number they called him, but Harada was one of those actors. He joined Haiyuza when I was still a member, and I remember thinking to myself, “Oh, now here’s actually a pretty good actor.” What made him a good actor for me was how he just felt like the real deal. That, and that strangely appealing voice of his. Although that’s not to say his voice was beautiful by any means.

It’s strange. Even now I don’t really understand actors. You have great actors, bad actors, okay actors… But also actors that are awkward but who still have a presence about them. It’s not just one single quality that determines an actor’s merit. What does it mean to be a good actor? Is it better to be “just” an okay actor, or is it better to be an awkward actor but with a presence? That kind of thing. Well, in any case, Harada did have a presence. That much is for sure.

Afterwards, he kept working on movies. But while I kept doing mainstream films, he went towards the more avant-garde films of directors like Terayama Shuji. He stopped doing theater altogether.

He was quite good in Hunter in the Dark, too. For me, it was a joy just getting to co-star with a beloved junior of mine. I’m someone who has never felt much in the way of feelings of greed or rivalry. Well, I did have a sense of rivalry towards my seniors, but when it came to my juniors I always wished to be supportive. From Harada’s point of view, with me being ten-something years his senior, I’m sure he felt nervous. But I think that nervousness worked in his favor. I very much liked him, and he looked up to me. It felt the same way to me as it had with Yamazaki Tsutomu in High and Low.

The last film we did together—even though we didn’t actually get to meet on set—was Zatoichi: The Last. He played a doctor while I played a bad guy. That was our last time co-starring. So then when the film was to be released and the actors got together to greet the audience at an advance screening, I ran into him and asked, “Hey you, are you all right?” I’d heard that he’d collapsed due to colon problems. He told me, “Oh, I’m all better now!” Those were the last words we ever exchanged. What a regrettable loss.

There are fewer and fewer actors like that around. I’m not talking about actors with skill, but rather actors with a sense of presence; a mysteriousness. When I look at young actors today, sure, they might be good-looking or what-have-you, but they have nothing on the inside. I don’t mean to say that we were “better,” but film stars and theater actors of the past had this certain mystery about them. We didn’t have anything like the internet back then, so our private lives remained a mystery. Take someone like Takakura Ken, for example. You had no idea how Takakura Ken was living his private life.

Back in our day an actor was an artist, in a good sense of the word. People saw movie stars as something beyond reach. But now, perhaps due to the influence of TV and the internet, even their private lives are laid out bare for all to see, removing any sense of mystery. Harada, despite his youth, still retained that mysteriousness. I think that’s what gave him his appeal as an actor.

Nakadai’s beloved Haiyuza junior, Harada Yoshio

“Onimasa” & Iwashita Shima

In 1980, Gosha was arrested for illegal possession of firearms, and as a result he retired from Fuji TV at his own request. Determined to make a comeback, Gosha’s first work following his arrest was 1982’s Onimasa. Based on a Miyao Tomiko novel, the film is set in Kochi in the early days of the Showa era, depicting the tempestuous life of a group of “self-styled humanitarians.” Nakadai plays the leading part of “Onimasa,” a yakuza boss and father of titular character “Kiryuin Hanako.”

Getting to do Onimasa, I just thought to myself how glad I was to have ever met Gosha. Toei’s president Okada Shigeru, however, did have some concerns which he expressed to me. He felt that up until that point in these kinds of yakuza films, when it was someone like Takakura Ken he would hold back the entire movie before finally pulling out a knife at the very end. But with my role, he felt that my sword was drawn from the very start of the film. He was worried whether Toei audiences would appreciate that sort of a movie. This guy with his sword drawn from the onset, talking non-stop in his Kochi dialect, and despite having a wife and several mistresses, the only person he blindly loves is his own daughter… What Miyao had written was all too real.

As an author, Miyao was unsparing even towards us actors—in terms of her spirit, she was right up there with the likes of Yamasaki Toyoko. Whenever we were making one of her books into films, Yamasaki would tell me, “No no no. That’s all wrong, Nakadai. That’s not at all what I was trying to say in my writing.” And then I would apologize. That happened a lot. Miyao was equally as relentless. However, just this one time she did give me high praise. “You got it right with Onimasa.”

When I do roles like that, despite the character’s stupidity, I play them straight. I can’t express myself in a straightforward manner when I’m playing the intellectual type. But in that yakuza setting, I’m able to put myself out there completely. I can be self-assertive. That’s what I liked about it. There’s a naivete about that role. Of course, it’s present in Miyao’s original work as well. The character is both sharp and dull at the same time. In a way you feel sorry for him, but then in a way he’s also just ridiculous. At any rate, he is an outlaw just the same. That’s what made the role so much fun to play.

Iwashita Shima plays Nakadai’s wife in Onimasa. After playing father and daughter in director Kobayashi Masaki’s Harakiri, the two also co-starred in many of Gosha’s works.

By my recollection, Iwashita Shima was only just about 20 years old when we did Harakiri. Her most striking scene in Harakiri was the one where the corpse of her husband in the film, Ishihara Akira, is brought back to their house after he has committed seppuku.

At first she just sits there. She bares it. But once Tanba Tetsuro and his gang—who deliver the corpse—leave the house, she throws herself at her husband’s dead body and weeps. Then, she returns to their child. Now, in that scene, director Kobayashi Masaki had instructed her to simply go and sleep by the child’s side. But when she went to lay beside her child, Iwashita—completely of her own accord—breathed this large sigh. Keep in mind: the director did not tell her to do this. When I saw that, I just thought to myself, “Ahh. This girl has got a future.”

When she played my wife in Onimasa, she asked me, “Nakadai, I wonder, how does the missus of a yakuza boss walk?” It’s not like I knew anything about that world either. But just as it was with Yamada Isuzu in Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, or Mizoguchi’s Street of Shame, it felt to me like most of those yakuza missuses of the time were former prostitutes. Look at someone like Wakao Ayako in Street of Shame for example. You notice how they all walk duckfooted. So I told this to Iwashita, and afterwards whenever I saw her walking into the film studio, she would be walking like that even then. That’s how passionate of an actress she was.

Natsuki Mari plays the wife on the opposing side. With the high-spirited delivery of her lines, she makes for a fitting opponent to Nakadai.

One of the most memorable bits of the film was that dogfight scene in Tosa. It was an outdoor set, but we put up a tent and filmed it there. It was all done under the guidance of professionals, of course.

The highlight of that scene was Natsuki Mari. When you’re talking about Onimasa, there were of course Natsume Masako, Iwashita Shima, and then Natsuki Mari. I believe it was her first role after making the switch from singing to acting. Her sharp way of speaking… That was all her fervent wish of becoming an actress, reflected in her performance.

The Wonderful Natsume Masako

Ultimately, however, the highlight of Onimasa must surely be Natsume Masako in her striking performance as Nakadai’s adoptive daughter, “Matsue.” From the intense sex scene where Nakadai throws himself at her, to her famous line “nametara ikan ze yo!” (“don’t you look down on me!“), her dignified appearance left a lasting impression only for her to pass away later in 1985 at the young age of 27, making Onimasa the representative work of a life cut much too short.

I have acted with many actresses, but if there is one woman who I was truly enchanted with from the bottom of my heart, it was her. Of course, I have acted with many women who were truly amazing as far as their acting goes. But if I was on my deathbed and someone asked me, “Who was the one actress you truly fell for the most?,” then my answer would have to be: Natsume Masako.

There aren’t a lot of people out there who possess charm both as a woman and as an actress. But that is what she had. She was attractive not only as an actress, but as a woman; as a human being.

She was already ill when we began shooting Onimasa. One day, before we started filming, she came up to me and said, “Mr. Nakadai, I want to let you know that I have an illness and so I have this big scar right here. Since we are going to do a sex scene later, I’m going to show it to you in advance. Okay?” She then proceeded to open her kimono and show me the operational scar she had on her chest. In that moment, I thought to myself, “This is one amazing person.” She was taking into consideration her co-actor even at her own, personal expense.

I was so struck by that act of hers, I ended up teaching her all kinds of things in regards to acting. Her line “nametara ikan ze yo!,” that line became very famous. It was actually me who told her what tone of voice she should use to say it. “In this situation, this is how a yakuza would act; this is how they would speak.” And she took my advice completely to heart and spoke her line exactly like that.

What’s more is that not once did she let anyone on set see that she was ill. Watching her and seeing how she cared for all of the staff and her co-actors like that, I just remember thinking to myself… “This is one wonderful woman.”

“Fireflies in the North”

Following the success of Onimasa, even as the Japanese film world was going through a period of stagnation in the 80s, literary style films which shone a spotlight on women from the Meiji era to the early days of the Showa era continued to be a hit among audiences. Playing a central role in that trend were Gosha’s films The Geisha and Oar, again based on Miyao’s original novels.

With Nakadai, he shot Fireflies in the North (1984). Set in a Meiji era prison in Hokkaido where the interred criminals are made to cultivate land in the wilderness, it’s a story about the demonic prison warden, played by Nakadai, who oversees them. Like in Onimasa, Iwashita Shima again plays his lover, while Mori Shinichi sings the film’s famous theme song, “Kita no Hotaru.”

As we were once again in pursuit of real snow, it was another film which we went to shoot all the way up in Hokkaido. It was a large-scale film in that sense, although one could say it also lacked precision.

It featured that big hit song by Mori Shinichi. That was the first time I met him. The songwriter Aku Yu was there as well, and we all had drinks and food together. Gosha was also there, and he and Aku were discussing what kind of a song it ought to be. Well, although I was present, it’s not like I gave any input in that conversation.

Fireflies in the North is like this entertainment film based hardly on anything, and yet, pieces of the story such as those prisoners having built most of the major roads in Hokkaido are actually true. But that bear attack scene… It’s not like they could use a real bear so they used a stuffed one instead, but I just thought it looked so terribly fake.

But things like that scene where the prisoners are walking in the snow as they are being moved from the prison, and the prostitutes are watching them… Those kinds of portrayals are what Gosha excelled at. It doesn’t make much sense plot-wise—he shows the story in images. The prisoners coming out of the prison into the snowfall while the prostitutes pursue them in tears, and then that song by Mori Shinichi starts to play… Carefully creating that sort of visual beauty, there was a kind of extravagance about the film.

And of course, speaking of this film, it also had my sex scene with Iwashita Shima. I’d sometimes think to myself, “How does Gosha manage to get the actresses so naked?” That’s how good he was at shooting sex scenes. They’d all undress without a word of complaint. In Fireflies in the North, Iwashita gave such a realistic performance that Gosha later came up to me and asked, “…Did you two actually do something?” But no, we didn’t. She just showed it all in her facial expression. She was so brazen in that sex scene, I have to wonder if there are any actresses out there today who would even be capable of doing the same.

Gosha’s Final Years &

The Appeal of the Outlaw Lifestyle

Entering the 90s, Gosha Hideo became ill, and after filming his 1992 movie The Oil-Hell Murder, he passed away in August of that same year from esophageal cancer. His final collaboration with Nakadai was Heat Wave produced in 1991, the year before his death.

Gosha was already in bad shape during the making of Heat Wave. We both used to be smokers back then, but then suddenly during the filming he said to me, “Moya, I had to give up smoking.” So instead what he’d do was, when we ate, he’d take the chopstick wrapper, fold it approximately into the size of a cigarette, and he’d “smoke” that. “When I do this three times, it feels like I’m smoking a cigarette.” That was Gosha’s sedative in those days.

I do feel like he didn’t have much strength left by that point. He didn’t have the kind of positive forcefulness that he’d had when making Hitokiri or Onimasa, and even on set he appeared rather tired.

Gosha was a master when it came to creating characters who were outlaws; characters who looked down on the society they lived in. You could even say that the outlaw was the only type of character he would depict. I suppose that could have its roots in how even his own father was a huckster.

Heat Wave was the last film I did with Gosha. We went to a hot spring together at the time, and his body was covered in tattoos. We’d gone to the hot springs together earlier when we were younger, too, but back then he didn’t have any tattoos at all. Perhaps he had a premonition of his impending death, and he chose to mark himself as the outlaw that he had always felt himself to be since birth.

At the risk of exaggeration, I feel that art, or performing arts, or just making things is in itself something that outlaws do. We make films to resist order—especially the bad sort of order. Like we’re fighting pointless “common sense” with senselessness. It’s an attempt to take that existing common sense and turn it upside down. Because there is nothing interesting whatsoever about films that are pure common sense.

Gosha himself is the pinnacle of a “senseless” director. In Onimasa, Sendo Nobuko played Natsume’s role of “Hanako” in her childhood. There’s a scene where her father makes her and his mistress fight it out in front of him. “Which one of you is lying to me?!” Gosha had her get into an actual exchange of blows with an actress who was an adult. Then, afterwards in that same scene when she experiences her first menstruation, even there he maintains a bird’s eye shot of Sendo as she rushes to the bathroom. Really, what a yakuza of a director he was!

That’s all part of us trying convey something to the audience through images. The type of film I hate the most is one where they try to explain everything through dialogue. In my mind, every screenwriter who writes like that, as well as every producer who accepts that kind of work, is second-rate.

In Gosha’s films, Nakadai consistently played the outlaw or the role with a strong presence of evil. Nakadai himself feels a personal attachment towards these types of roles.

The majority of the roles I’ve done have been like that. Even in The Human Condition, while my character might at first glance seem like a champion of justice, he’s not just a simple hero—he’s someone who opposes war, all by himself. So he’s a weird one, especially when compared to the average Japanese person at the time.

I often play characters with personality complexes or negative aspects to them. Even in period dramas, I’ve been cut down by Mifune so many times. In the sort of entertainment films where poetic justice exists, I’m always the bad guy who dies at the end—although that is also the case with the Kurosawa films I did, too. But they all share that same sort of an attitude towards life, and I enjoy performing said attitude. Someone like “Takechi Hanpeita” in Hitokiri, he never actually even draws his sword, and yet he’s still truly evil. Or something like Conflagration… I really have done my fair share of roles that have something negative about them.

My wartime experiences, having been so poor since birth, living almost like a beggar… Lately, I feel like maybe even as an actor I’m still hung up on my past. All along, maybe I’ve been using those sorts of life experiences as the foundation of my work as an actor. That must be why I enjoy playing characters burdened with insecurities or negative characteristics.

Was looking forward to reading this chapter and you didn’t disappoint. Thank you!

Glad you enjoyed it. Catch you in the next one!