Working with Kurosawa Akira

“Yojimbo,” “Sanjuro,” “High and Low”

“The World’s Kurosawa.” The master, Kurosawa Akira. Discussing Nakadai Tatsuya’s filmography would be impossible without mentioning his work with Kurosawa. In the 1960s, he played in roles opposite to Mifune Toshiro in the period dramas Yojimbo and Sanjuro, and then in the role of a detective relentlessly pursuing a kidnapper in the suspense film High and Low. Later in the 80s he also played the leading parts in Kagemusha and Ran.

In this chapter, we begin by discussing the three works from the 60s.

The Humiliation of “Seven Samurai”

Nakadai’s first time at a Kurosawa set was during the filming of the 1954 Toho film Seven Samurai. This was the tremendous period drama that would earn Kurosawa Akira permanent fame as a film director.

I was a second year student at the Haiyuza Training School and just around 20 years old when I took part in the auditions for Seven Samurai. It was only a tiny scene lasting a few seconds, but I did appear in the movie as an extra. In one of the opening scenes when the farmers are searching around town for mercenaries to protect their village from bandits, I played the role of a ronin who caught their eye.

It was my first time wearing a beard, first time wearing a topknot, first time wearing a sword… And yet, Kurosawa was suddenly telling me to lead the group. To be fair, I’m sure it was just because I was physically the biggest one of us.

However, just as we started shooting, Kurosawa suddenly began yelling at me. “What the hell are you doing, walking like that?!” We tried it over and over again, but each time it was no good. And no wonder—shingeki acting never taught me things like that. Besides, I was wearing a kimono for the first time in my life.

We started shooting at 9 in the morning and we only finished the scene at around 3 in the afternoon. Meanwhile, I was making a hundred actors and staff wait around just because we had to do take after take of this scene of me walking. I guess it speaks to the state of luxury the world of cinema was enjoying at the time—they could afford to spend all that time on a scene with just one extra.

It was because of that experience that I became thoroughly conscious of the way actors walk, especially in period dramas. But even then that’s not to say I could do it properly right away.

Nevertheless, I felt humiliated. I was an extra—it’s not like there was no one there to replace me. And yet, Kurosawa just kept doing take after failed take using me while I was making Mifune and everyone else wait. I began to hear insults coming my way. “What is wrong with this guy?” “Someone make sure he gets no lunch!” I was so humiliated I thought to myself, “I’m just not cut out to do movies. Especially not period dramas. Never again.”

Being Cast in “Yojimbo”

Nakadai’s first important role in a Kurosawa movie was in the ’61 period drama Yojimbo. He had become an overnight top star in ’59 with director Kobayashi Masaki’s blockbuster The Human Condition, and Kurosawa now had his eye on him.

We spent half a year filming the first two parts of The Human Condition and then went on a half-year break to prepare for parts three and four. It was during this time that I was approached about Yojimbo.

At that time, I had just managed to make a bit of a name for myself as an actor. Kobayashi and Kurosawa were friends, and so apparently Kurosawa asked Kobayashi if he wouldn’t mind “lending” me out to him during the break before the next two parts of The Human Condition.

When I first heard of this I could still vividly remember my humiliation from Seven Samurai, and so I declined the offer. But try as I might to turn it down, Kurosawa just wouldn’t give up. I spoke to Kobayashi about it and he said I should give it a shot. “If the role was anything like “Kaji” in The Human Condition, I wouldn’t like it. But it’s a totally different character so why not just do it?” While “Kaji” was this heroic, righteous humanist, the yakuza by the name of “Unosuke” in Yojimbo was a cold-hearted villain. But even so, I kept trying to run from it.

But then finally Kurosawa caught me at this hotel out in Shibuya called Kikuya, and he forced me to speak to him. “Why do you keep turning me down? Do you not like the script?” I told him all about what had happened during Seven Samurai and how I’d decided back then that I would absolutely never collaborate with him ever again. Well, you know… I was young. The nerve of me to say that to “The World’s Kurosawa!” Anyway, he then said that he actually remembered what had happened. “That’s the reason I want to use you!” Obviously, hearing him say that, there was no way I could’ve turned him down. And like that, I ended up agreeing to appear in the film.

Yojimbo is an exhilarating western-style period drama in which a lowly samurai called “Sanjuro,” played by Mifune Toshiro, shows up at a certain inn town where two yakuza organizations are caught in a dispute, and “Sanjuro” proceeds to destroy them both. “Unosuke,” played by Nakadai, is a member of one of those organizations. Armed with his intellect, he gives “Sanjuro” plenty of trouble, becoming his biggest adversary. Wearing a concealed pistol in his breast pocket and a red scarf around his neck, this very “un-period drama-like” outfit caused a stir among audiences at the time.

Critics who were particular about their background research disapproved of the movie, talking about how “no one was wearing scarfs like that back then.” But Kurosawa went, “Bring those critics to me!” He presented his counterargument. “Near the end of the Edo era they were doing trade with the English. Even scotch whisky was finding its way into the country, so surely there would have been some Japanese who were wearing red scarfs of all things. And “Unosuke” is a flashy guy, so that is what he wore.”

But that wasn’t the real reason. Kurosawa explained to me how actors in period dramas used to be more bullnecked—that’s what made the armor and kimono suit them so well. But I happen to have a very long neck, and apparently it didn’t look cool coming out of the kimono like that. He even joked how he would’ve preferred someone with a shorter neck for the role. It was when he was thinking about how he could best hide my neck that he came up with the scarf idea.

That’s the kind of person Kurosawa was. The journalists would ask him, “What’s the theme behind this new movie?” And he would reply, “There is no theme. I just film what I want to film.” But he did have a theme—his idea of one anyway. In the case of Yojimbo it all started with him thinking, “How could we get rid of all yakuza?” Because he hated the yakuza. So he came up with the idea of the yakuza fighting each other. That was the theme.

What excited audiences the most about Yojimbo was the final duel scene between “Sanjuro” and the yakuza faction led by “Unosuke.” In the scene, “Sanjuro” throws a concealed knife at “Unosuke,” knocking down from his hand the biggest source of his troubles: the pistol. In the next instant, he quickly cuts down six of the yakuza in one fell swoop. Up until this point in time, the “beauty” of fights like this had been the selling point of period dramas. However, Kurosawa instead refined the scene to modernistic, genuine action. It was revolutionary.

Mifune walks towards us. We, the yakuza, walk towards him from the opposite side. I tell him not to come any closer. Mifune does so anyway. I move, too. He grabs not a sword but a knife, and just before I shoot he throws the knife at my wrist, making me drop my pistol. They shot all this in one take with two or three cameras and it felt like it was over in an instant.

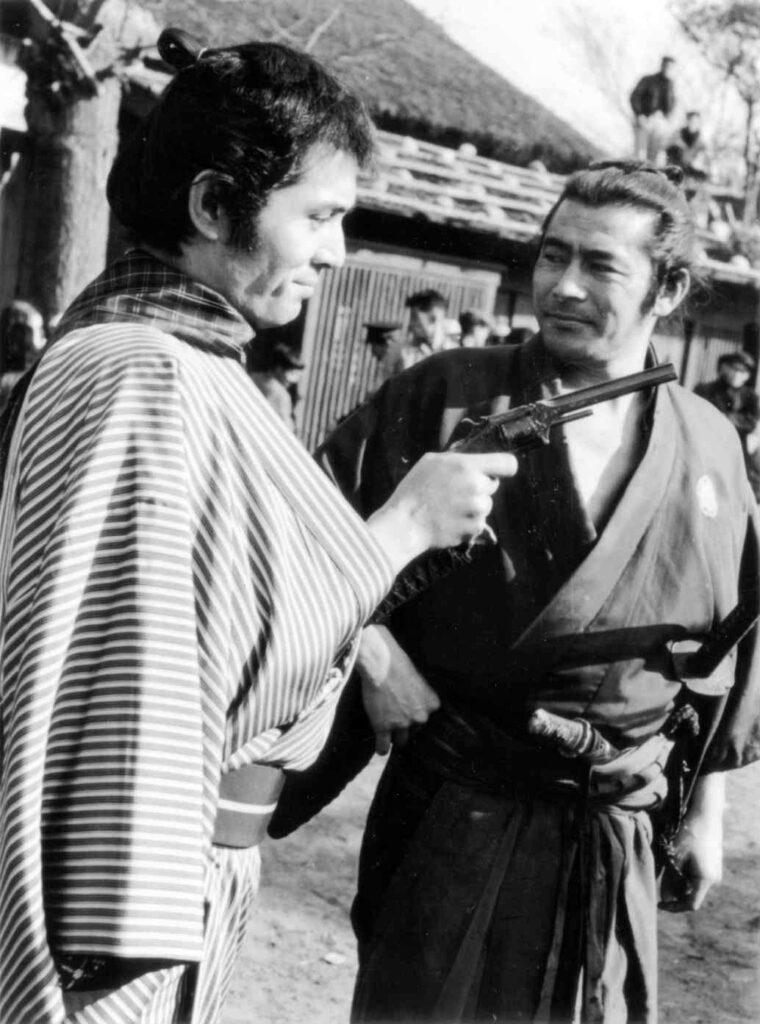

“Unosuke” shows off his pistol to “Sanjuro” during a break in filming

What amazed me the most about Mifune was… Let’s say there was a scene where he was going to cut down ten people. Kuze Ryu, our choreographer for the sword fight scenes, would talk him through it. “Okay, Mifune. So you move like this, and then like this. There will be a camera over here. It will come at you like this, and you will move like this.” He will go over every last detail with him. And Mifune just says, “Okay.” Kurosawa asks him, “Good to go, Mifune-chan?” Mifune simply tells him to go ahead, and then it starts for real. And before you even know what’s happening, you hear Kurosawa going, “Okay, cut!”

I have acted in many fight scenes with many period drama actors, but Mifune was the greatest one of them all. Especially his strength and the speed of his technique. Traditional period drama actors cut down people as if they were dancing, but Mifune, he would actually make contact with you. That made it seem as if he was genuinely cutting people, and furthermore he could cut nearly ten people in ten seconds—one second per one person killed. That all made for an unprecedented intensity.

At any rate, it was his movement that was great. He had great physical ability—that’s why he was so good at fighting, too. Moreover, he was always giving it a 100% even during test shoots. He was moving so hard he would actually break sets. Kurosawa would be yelling, “Stop breaking the set!” So then we just ended up doing everything without any rehearsals. That was the case for pretty much all of Yojimbo. That made it a fast shoot for Kurosawa.

However, that movie was all shot through a telephoto lens. That part of it was a challenge. Normally the cameras are close to you, meaning it’s easy to tell by looking at the height and distance of the camera approximately how much of you is being captured. But this time because it was a telephoto lens, that meant the camera would be further away. I’d be acting while thinking it was a wide shot when Kurosawa would start yelling at me. “You idiot! I was taking a close-up of you!” Telephoto lenses are usually used to film something far away, but he was using it even to shoot close-ups. That meant that I could be walking and if I lowered my head even a little bit, I would be out of frame.

The actors in westerns pull out their pistols from the waist. But my character in Yojimbo wore a kimono so I would pull mine out from my breast pocket, meaning the pistol would end up being directly in front of my face. While there were no bullets, it did have gunpowder inside to produce the firing sounds. My eyes would instinctively close when I shot it… And when they did, Kurosawa would once again start yelling about how he was taking a close-up of me.

Another difficult thing to deal with was all the dust. Yojimbo was meant to have a western feel to it, so there were always these incredible clouds of dust whirling in the air. We used this mix of roasted soybean flour, sand, and salt. We shot it in the winter, so the salt was mixed in there just so it wouldn’t get frosty. That stuff made it nearly impossible to keep your eyes open, but of course Kurosawa would be ordering us to do so anyway.

It made me see how remarkable those telephone lenses are, and how you couldn’t get careless around them. What’s more is that Kurosawa would never tell you in advance if he was going to shoot a close-up of you. He only said, “You should all be prepared for that possibility in every scene.”

I suppose I managed to endure it because I was in my twenties. Or rather, I’m glad I was only in my twenties when I first met a person as intense as him.

“Sanjuro”

After Nakadai had finished filming Yojimbo and parts three and four of The Human Condition, Kurosawa came to him with another offer. This time it was for a film first shown over the New Year period of ’62 and the continuation of the series: Sanjuro.

In this film, Nakadai once again found himself standing in “Sanjuro’s” way. The name of his character was “Muroto Hanbei.” Coming to the aid of a group of young samurai burning with the fire of the Hansei reform, ”Sanjuro” challenges the opposing, conservative chief retainers. He then finds himself in direct conflict with the chief retainers’ strategically-minded master fencer.

I was very pale around the time of Yojimbo. Kurosawa saw that and said, “Your character is also pale and there’s this crookedness about him… I don’t think we need to have you do any make-up.” Thus, I played “Unosuke” with almost no make-up.

But for Sanjuro, he said it was going to be something different. I asked him if I was going to be a warrior, and he said yes. “But not only are you going to be a warrior, you’re going to be a very strong one. We need to make you look like someone who it feels like even our Mifune might lose to.” In Yojimbo, I wore no make-up and a scarf… Well, in a word, I was an unpleasant guy. But this time I was to play a simple man. I was going to be a warrior like “Sanjuro.” Two kindred spirits who found themselves in two different situations and who were thus forced to fight.

I asked Kurosawa what age I was supposed to be, and he said “around the same age as “Sanjuro”—a little under or over 40.” And yet, what they had prepared for me was this wig for a much older man. With those period drama wigs, the narrower the space of the “shaved” part of the forehead, the nicer it looks. But with those wigs meant for older roles, the shaved off area is very wide all the way to the topknot. That can give it this unseemly look. So they made me wear it, and I looked like a damn octopus! But that’s how I was supposed to look—it was a perfect fit for the dazzling “Muroto Hanbei.” On top of that, they painted my face all dark with greasepaint.

Kurosawa was very particular when it came to visuals, and so we spent over a month establishing the look of my character in make-up and costume tests. You would not get away with that in this day and age.

When speaking of the film Sanjuro, one can not avoid mentioning the final duel scene between “Sanjuro” and “Muroto Hanbei.” As they both draw their swords in a split second, Nakadai gushes out large quantities of blood. It had been a taboo to show blood in period dramas at the time, and the overwhelmingly graphic force of the scene left audiences dumbfounded. Furthermore, even in the script for this scene it said how “it could not be written what happened.” Details about the scene were kept secret, and when they went to film the scene no one aside from the director and a select few members of staff knew what was going to happen—not even the actors.

In describing the final duel, the script only said something along the lines of, “nothing more can be written.” I had no idea what the scene was going to be like. But because the sword battle in the previous film, Yojimbo, had been so amazing, I did have a feeling that it would be another tremendous fight. The final battle in Yojimbo had ended in a flash so I did expect it to be a quick one this time around as well… Just not that quick!

As a matter of fact, Kurosawa gave me and Mifune his instructions separately. Mifune learned his movements on his own and I learned mine—we never practiced together until the real deal.

What I was taught was the so-called iai method of drawing one’s sword—how to cut your opponent when they have attacked you in a cramped space. Drawing your sword too widely, you risk striking against an object around you. Instead, this method is all about unsheathing your sword and then bringing it to its target via the shortest distance possible, cutting them down. I devoted myself to learning this technique and I spent a month practicing just that every day.

We filmed the scene in Gotenba. They attached a tube to the chest area of my outfit, the prop master buried the other end in the ground, and next to it there were these gas cylinder cans. The one thing I knew is that I would get cut in the end, so I could now guess that those cans would send blood shooting out of the tube attached to me.

Filming the actual scene, we stood facing each other for about twenty seconds before Mifune drew his sword from the left, and I drew upwards, cutting downward. Mifune being faster than me, his sword cut into my heart. Suddenly the blood began spurting out and it nearly sent me flying backwards. When I got cut, the prop master had sent the blood shooting out of the cans so hard that it just gushed out with such incredible force. No doubt, if we were to shoot that scene today, I would fall over. That’s how powerful it was.

But even though it all happened in a flash, my brain was working overtime. “Ahh, the blood came out! The script supervisor—Nogami Teruyo—is running away. The blood got all over her back… I wonder if her white sweater is okay?” I was also mindful of the fact that had I fallen over, we would’ve probably had to re-do the scene—they had around 30 extra costumes prepared in case of bad takes. But I thought, “No, I don’t want to do something this unpleasant again,” and I braced myself. I was young so I could do it. And me having to brace my legs had been part of Kurosawa’s calculations, too.

The young samurai like Kayama Yuzo and Tanaka Kunie were staring at us in stunned silence because even they hadn’t been told of what was going to happen—they thought Mifune had cut me for real. The cameraman, the director, the assistant director, and Nogami the script supervisor were just about the only people who knew, and even Nogami was caught so off-guard by it that she began to run away. They must not have been expecting that much blood to come spurting out.

In any case, we got it in one take. “All right, we did it!” That evening we stayed up all night at the inn just drinking in celebration. But then the next day, Kurosawa came to me and suggested we try it again! I protested, saying how we had all been happily drinking the previous day because it had been a good take. But he said, “Nakadai, when he cut you… You slightly closed your eyes.” Of course I did! I explained that if someone comes at you that fast, naturally your eyelids are going to twitch a little! I insisted that it surely wasn’t a deal-breaker, and finally he agreed. “Mmm… Now that you put it that away… Well, all right. It’s okay.”

Kurosawa was dissatisfied with the period dramas that had come before—the whole thing about people almost dancing beautifully as they cut people. He argued that cutting people wasn’t supposed to be “pretty.” It was Kurosawa who made the acting in period dramas more graphic. When you kill someone with a blade, there will be blood—there’s no two ways about it. That’s how Kurosawa saw it.

The main fascination with period dramas usually lies in the sword fighting. Even when compared to the whole rest of the world, sword fighting done with Japanese swords really is something unique. While we didn’t worry about our movement to the extent of all those Kyoto actors who specialized in period dramas, we thoroughly learned about things like how to walk when wearing a sword, how to draw and sheathe one’s sword, how to cut a person, and the proper way to wear a kimono. Since I myself came from the world of shingeki, I had to learn all that from zero.

But now in this current era of television, there are less and less people around to teach actors those things. That does make me worried about the future of period dramas. Watching all these television era period dramas, it’s commonplace to see actors whose postures are too loose—something which Kurosawa used to get so angry with me for. The producers probably don’t even know how it’s all wrong.

“High and Low”

In the following year of ’63, Nakadai also appeared in the suspense film High and Low with an entirely different setting: the modern era. He played the role of a detective in relentless pursuit of a kidnapper.

High and Low came next. It was based on a book by an author called Ed McBain. I actually really love Ed McBain regardless of the fact that the book was made into a movie. I’d always been reading his books ever since I was a child. Anyway, Kurosawa took his novel King’s Ransom and “Japanized” it very successfully. Mifune’s role as the shoemaker—that was truly a tour de force.

Kurosawa told me, “Nakadai, if it was up to me I’d really rather have had Henry Fonda play this role.” Yes… In the back of my mind, I was wondering if there was any good reason for him to be personally telling me that. Not even I could stop myself from quipping back at him. “I’m not Henry Fonda.” Kurosawa replied, “Well, play it like him anyway.” He further added that my face was “too narrow” compared to Henry Fonda. How could I help how narrow my face was?! So then he told me to come in for make-up every day before filming to have them shave my brow.

My role… He had zero sympathy for the criminal. On the contrary, it was something like the detective’s hatred towards the criminal that motivated him. His thinking was that if they were to catch him right then, he wouldn’t get the death penalty. That’s why he held that press conference—to try and get all the newspaper reporters to drive him towards that death sentence. “A man devoted to his profession,” I guess you could say. It was completely different to my roles in Yojimbo and Sanjuro. Kurosawa told me to just play it straight… And so I’d have my brow shaved every day. He told me, “You and Mifune both have a distinct aura about you. But this time, I want you to get rid of it.”

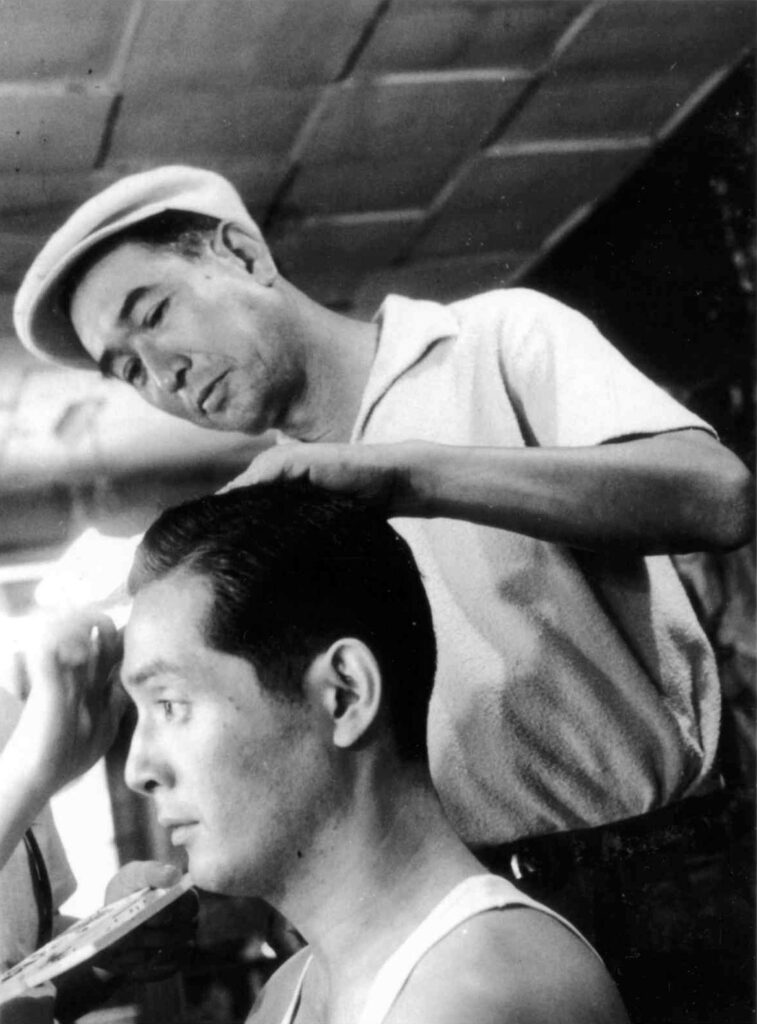

Director Kurosawa checking Nakadai’s hair

That scene where I enter Mifune’s home, that was a one-take scene lasting about ten minutes which we shot using about four cameras. For the scene where we hand out the money on the Kodama express train, we had about eight cameras on us and we were told that every failed take was going to cost them 20 million yen. This was back when spoken lines were all dubbed afterwards and it’s also what Mifune and I did here. Seeing ourselves and how fast we had been talking in the scene, it was obvious how nervous we had been when shooting the scene.

The press conference scene near the end was another long, 10-minute take. People like Fujita Susumu who had once been leading actors themselves were just sitting behind me in silence. I was doing all the talking. The newspaper reporters included people like Mitsui Koji and Otaki Hideji. It was just ten minutes of me talking to myself so I figured it wouldn’t have been a big deal if I’d caused ten or twenty bad takes before we got it… But somehow, I made it all the way to the end in one take. But then there was a certain reporter who had to say his line after listening to me talk for ten minutes… And he flubbed it. See, he had the tougher job. I could just stand there, talking about the criminal and his whereabouts and his recent activities and about drugs and all of that, but all he could do was wait for his turn so he could speak up at just the right moment.

Kurosawa always had someone he would pick on. In the case of this film, that someone ended up being Ishiyama Kenjiro. Playing the role of the Chief Detective, he was a veteran of the Shinkokugeki troupe. But Kurosawa just kept saying he was no good, take after take. Ishiyama was going, “What is it that you want from me?! I’ve been an actor for fifty years! You have humiliated me!”

But when it was done, his acting in it really was great. Kurosawa had a habit of coming down hard on people he thought had potential to do better. That’s something Chiaki Minoru would often say. “He doesn’t come after people like us because we can do an okay job.” Kurosawa wasn’t looking at actors like me and Chiaki in that sense.

*

After we finished filming Yojimbo I went back to do the next two parts of The Human Condition, then came back to spurt blood on Sanjuro, and then started on the final parts of The Human Condition. So that really was an intense four years. Even just the filming of The Human Condition alone was rough.

After having had those experiences, no matter how much someone was screaming at me I could just take it in stride. I’d been picked on so much when making Seven Samurai, but I was older now—I was no longer a teenager. Kurosawa never had a single request for me as far as my acting was concerned. Yojimbo, Sanjuro, High and Low—never during the making of any of those films did he offer me a single comment. It felt like I had finally rid myself of that lingering sense of humiliation from Seven Samurai.

This is amazing thank you so much for working on this.

Hey W!

I’m glad you discovered this translation and that you’re liking the book.

It’s definitely taken me longer than I anticipated to get to the next one (Chapter Three), but I hope to have it up before the end of the month.

The Seven Samurai anecdote reminded me of a short story, Film Star Mr Potol, by Satyajit Ray, the Indian film director. Mr Potol is an unassuming man who is offered a small role in a film by his neighbor, a production assistant. Mr Potol did amateur theater in his younger days, so he is excited by the prospect. When he shows up on location the next day, he discovers that it’s a tiny role: he will be bumped by the hero while crossing a street and he has to say “Ohh!”. He is initially disappointed, but he remembers his mentor had taught him that no role was too small. He thinks about the role, about the many different ways that one could say “Ohh!” to express irritation, surprise, etc. When cameras roll, he does his part flawlessly, and leaves the location quietly without waiting for payment.