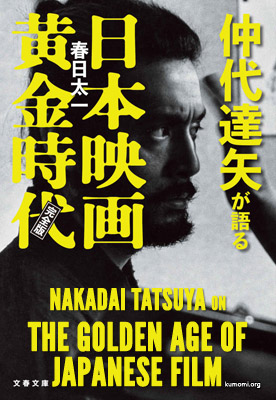

The Birth of Actor Nakadai Tatsuya

Nakadai Tatsuya has taken on a great number of completely different roles in his career as an actor. Many of those roles have had something about them that is entirely out of the norm; something that feels eccentric. Explaining his preference for choosing roles like that, there was one word which Nakadai uttered several times over the course of our interviews: “insecurity.”

Before getting into the main subject at hand I wanted to ask about the background behind that insecurity, delving deep into the origins of the actor, Nakadai Tatsuya.

Road to Acting

The Pacific War began on 8 December 1941. My father had passed away in May that year, and it looked as if our family was going to become separated—we were just so poor. I was but nine years old at the time.

My older sister was born from my father’s first marriage, and after his wife from that marriage passed away he then married a second time—this time to my mother. I was born next, and I was followed by a younger brother and a younger sister. I was born in 1932 in a place called Gohongi in Meguro, Tokyo, but we later moved to Tsudanuma, Chiba, because of my father’s job transfer. He was a bus driver for Kaisei Electric Railway, and since his place of business was moved to Tsudanuma, that is also where I entered elementary school.

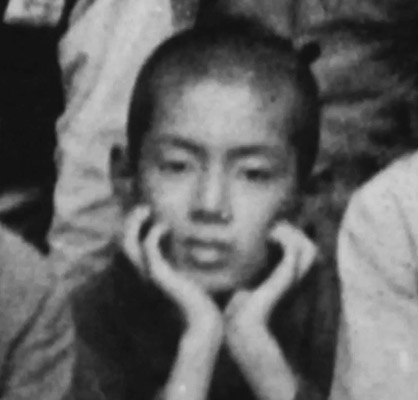

Nakadai family portrait (1933?)

Father Tadao on the left, and mother Aiko holding Tomohisa (Tatsuya’s birth name)

When my father passed away in 1941, we were rendered homeless. My family—my mother who had asthma, my big sister and me, and my little brother and little sister who were very young—were driven out of the company housing in Tsudanuma. However, through a happy coincidence we were then able to rent a tenement house near Youga—which is where the Mumeijuku Acting School can be found today—where my mother began working as an assistant at a dressmaker’s while my big sister found employment at a well-known futon store, managing to provide for our family. I then transferred to an elementary school in Youga.

Nevertheless, at some point it just wasn’t enough to support our whole family. Just then, we found an advertisement from an attorney’s office in Aoyama. They were looking for a house-sitter for their office, and the whole family could go. During the day we would serve tea in the office, and at night we would sleep there and take care of the building. The office was in Rokuchome, Aoyama, and my whole family moved in there together.

I transferred to Aoyama Elementary School. This was an elite school, the sort where sons of military personnel and politicians would enroll. Among my classmates were the son of Yamamoto Isoroku, and the son of General Anami Korechika who was the Army Minister at the end of the war. My mother had put us in this school that we really didn’t have any business enrolling in.

But this was wartime, and things like social status or disparity didn’t matter—bombs would be dropped on you just the same. Still, one day the teacher said to us how “this school isn’t the place for the likes of you.” My mother—always quick to lose her temper—became absolutely livid, threatening that she was going to sue the government for this, my teacher trying desperately to calm her down. That was my mother for you.

Young Nakadai

There was a mass evacuation when I was in fifth grade, and so me and my little brother had to move away from the rest of our family. But because ours was an elite school we weren’t sent far—they arranged it so that our family could still come visit us. I was evacuated to Senkawa on the Keio Line, while my little brother went to live in a temple near the next station over, Kaneko (now: Tsutsujigaoka). My big sister also moved into that temple with my little brother to work there as a housekeeper. My mother alone stayed behind at the office in Aoyama.

They started bombing Japan even prior to the Great Tokyo Air Raid. Their first target was the Nakajima Aircraft Company airfield—a military base right next to Senkawa. So although it was supposed to be my “evacuation spot,” there were Grumman fighters firing their machine guns at us. We’d run and hide in the nooks of graves at the temple. This was a very difficult time for me. We would eat toothpaste because there was no food. Some of the children would eat their own feces. That’s how badly starved we were.

In 1945, I graduated elementary school and I was returned from my place of evacuation to my Tokyo home. When I got home, however, there was this strange baby there. I asked my mother, and she told me that he was my little brother. My mother had… Well, it was the child of her and the attorney. But the attorney also had a legal wife, so my mother was basically his mistress as it were. Seeing as he now had a newly born son, the attorney rented us a house in Shibuya. Just after we moved to Shibuya, that’s when the major air raids began.

I was supposed to start junior high school in April 1945, but of course there had been nothing in the way of entrance examinations. So then that attorney… What should I call him? I couldn’t exactly call him my “stepfather”… In any case, his younger brother was the vice principal of Kita-Toshima Technical High School.

At the time, I was living near Chitose-Karasuyama on the Keio Line. So what I would do is, I’d take the Keio Line from there to Shinjuku, then the JR Line from Shinjuku to Ikebukuro, then the Tojo Line from Ikebukuro to a place called Naka-Itabashi which is where Kita-Toshima Tech was. However, as there were air raids occurring nearly every day, we would have air raid alarms going off all the time at school. I would be walking past charred corpses on my commute. I then quit there and enrolled in a school right by Chitose-Karasuyama, the Tokyo Metropolitan Heavy Equipment Technical School in Setagaya, which is where I graduated. And then the war ended.

*

Had I been just five years older, I’m sure I would’ve been called up for military service. Back in those days the only thing on my mind was dying for my country; dying for His Majesty the Emperor. I suppose it was a little bit later on when I became in many ways more critical in my attitude. But for us people born between 1932 and 1935, pretty much the only thing they were teaching us was dying for His Majesty. “One Hundred Million Shattered Jewels” and all the rest of it. They made us train with bamboo spears every day—there was a commissioned officer at our elementary school who said it was in preparation for us one day having to fight American troops “if push came to shove.” Thinking back on it now, one might ask what the point of us doing any of that was—they’d already dropped the atomic bombs on us.

We believed everything we were told, and so we all thought of them as “Western savages.” But then in the space of just one day, 15 August 1945, the adults all suddenly became pro-American. In my young boy’s mind, I found myself deeply thinking about people—that is, the same people who had just been constantly talking about dying for the Emperor. I became very distrustful of others.

We were struggling to make ends meet. Chiba High School—previously one of Tokyo’s number one schools—was also at Chitose-Karasuyama. I got into night school and spent four years there. Most of my days were spent in junior and elementary schools in Karasuyama, working as what you might call an “office boy.” Serving tea. What I did the most though was make copies on the mimeograph.

The Japan Teachers’ Union was taking a strong stance at the time… They were all communists so they’d always talk about how there should be zero disparity between people. “That’s what communism is all about,” they said. But even as they were saying that, they would send me out every day to buy them snacks for lunch. While I myself had absolutely nothing to eat, I would go out to buy them croquettes, hand them out to all the teachers, and when I did so, not a single one of them would offer me one. “To hell with communism,” I thought.

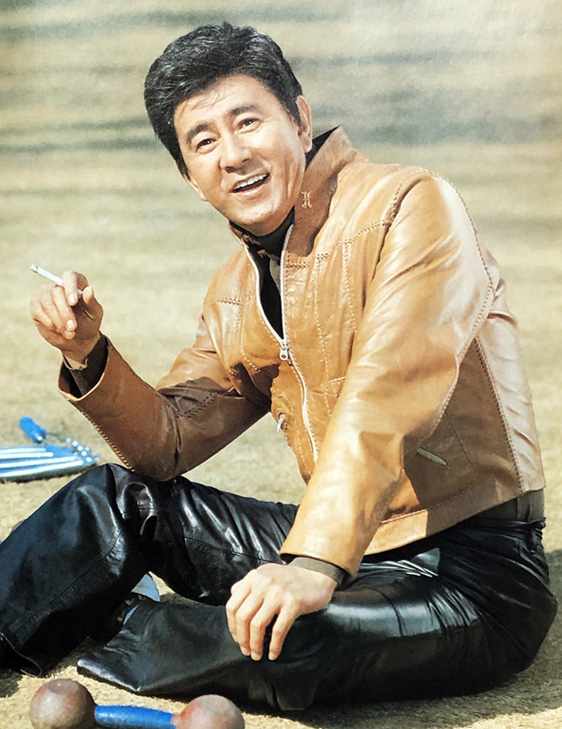

Nakadai at around 19 years old

I was working various part-time jobs, living day by day in those fire-devastated areas. I was an extremely timid child who felt embarrassed being around people. I didn’t have the slightest intention of becoming an actor—I’d never even appeared at our school’s arts festivals. But being a mere night high school graduate, I just wasn’t making ends meet. This was a time when it was difficult even for university graduates to find work. They say it’s difficult now, too… But this was much worse.

You know… I went to this yakiniku place the other day, out in Youga. A rather expensive place at that. Honestly, the place felt a little pricey even to us, and yet there was a family with five or six kids there, and they were all ordering their favorite meats. You go to a sushi place now and there will be families ordering toro pieces like it’s nothing. It’s like, “Hey, wait a minute! Is everyone here loaded?!” Sure, overall it might still be an economically harsh situation today. But compared to the state of emergency during wartime? Back then, it was a question of whether you would have a single grain of rice to eat that day or not.

The motivation for me turning to acting was simply because I had nothing to eat. I was working at the Ohi Racecourse at the time, and one of my work buddies said to me, “Hey, you’re a good-looking guy. You should be an actor!” That’s it—his remark was the entire reason behind me thinking I’d become an actor.

I love Western films. I would watch around 300 films a year, managing to do so by eating one meal a day instead of three. I would walk home all the way from Shinjuku to Chitose-Karasuyama, staying up all night just so I could see one movie. That’s how much I loved them. They were American and French movies—Japanese films up until that point had all been nationalistic propaganda. I thought those foreign films were interesting just because they were showing me all these new worlds. “Ah, so there’s this kind of a way of life, too.” “I wish I could be like this protagonist.” I had a strong sense of that.

Buying the pamphlets at the movie theater, they would have the biographies of all the actors. Reading through them, it was obvious how the actors had always, without exception, studied their fundamentals somewhere. America and France both had university drama departments and acting schools—France even had a national one. But in Japan, in the case of theatrical plays, you would first spend many years as a research student, and then those with some ability would join a troupe. In the case of movies, they’d just hire the new faces, give them the leading roles, and those who were no good at it would continue being no good while those who could improve would improve. That was about the extent of Japan’s “acting literacy.”

It was right around this time when I learned of the existence of a certain academic acting school.

That was the Haiyuza Training School. I thought I would apply—my thinking was that I would learn as much as I could of the fundamental, academic aspects, and then I could become an actor. And so just by chance I decided to apply—and just by chance I managed to get accepted. Apparently, Haiyuza Training School’s policy at the entrance exam was that rather than judging the level of your acting, they simply chose people who were physically large.

I got in as part of the fourth generation. Previously I had been working during the day and going to night school, but studying at Haiyuza was similar to taking university lectures, meaning I would be at there at the training school during the day and then working at night. I spent two years working at a pachinko parlor. I don’t know how those parlors are these days, but back then I would be there behind the machines adjusting whether balls would come out or not—that was all my job. I would usually only get to sleep at around 3:00 at night, and then wake up at around 7:00 so I could make it to acting school by 9:00, which was when training would begin.

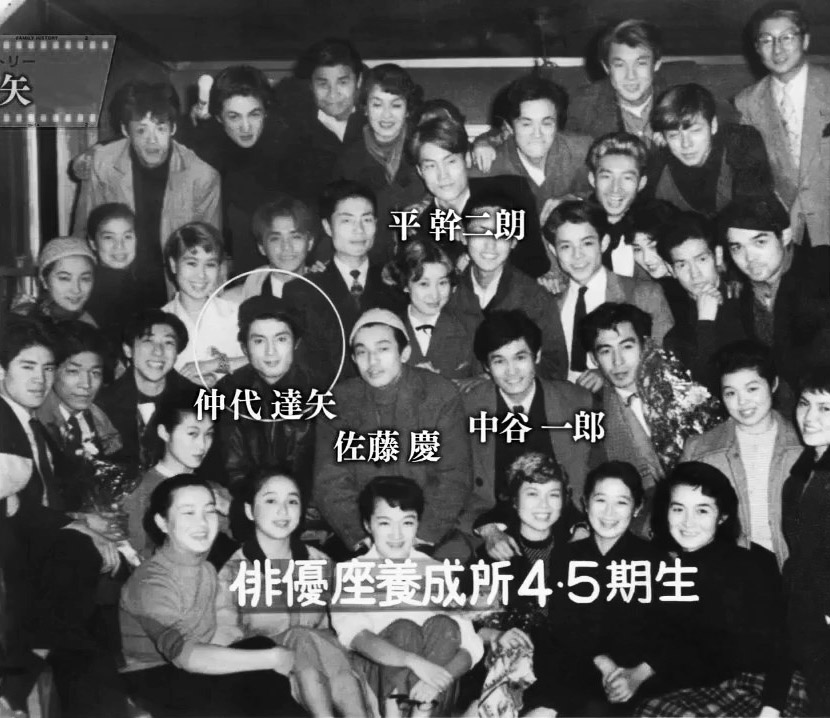

Fourth and fifth generation members of the Haiyuza Training School

Nakadai is circled

I had no money. Every day I would somehow scrape together the cash for my train ride to Shibuya, and then run from Shibuya to Roppongi where the training school was. Summer or winter, I would always be wearing the same clothes—I’d just wear more in the winter.

In addition to that kind of a daily existence, I was also born with a natural gloominess. I disliked being around people.

I was always withdrawn and untalkative ever since I was little. I never appeared at my school’s arts festivals. My mother told me that, yes, while I did cry out the moment I was born, apparently from that point onwards I never cried again; never grumbled. One time she even took me to see a doctor because she thought I might have had a stuttering problem. That’s how little I spoke. This continued to be the case all through junior high and high school.

Because of that insecurity of mine, I felt like I would never be able to surpass anyone if I just did what normal people did. Because even at the training school I had fifty generation-mates—that is to say, fifty rivals.

Haiyuza Training School

Nakadai began his life as an actor at the Haiyuza Training School. Haiyuza—with Senda Koreya at the top and also featuring many outstanding supporting film actors among its ranks, including Tono Eijiro, Ozawa Eitaro, and Mishima Masao—was a popular shingeki troupe. Each year a great number of young actors would graduate from its training school, providing sustenance to the world of Japanese film and theater.

In the beginning after I’d made it into the training school, they wouldn’t give me any lines at all. It was all just… “Be a lion.” “Be a cat.” “Now be a bear.” I was just doing animal poses and screaming.

I was struggling even to pay the monthly tuition fee, and here they were making me pretend to be a lion. But as a matter of fact, that was all just training for my vocal cords. Actors—especially shingeki actors—will be doing things like Shakespeare on stage, and there the number one priority is to be able to vocalize properly.

The second thing was the “art of speaking.” You had to make it so that even if you lowered your voice somewhat, you could still be heard in a theater that seats 1500 people or so. Once we could do that, we then had to make it so that we could be audible even when whispering; even when just breathing. I spent two years learning that skill.

Another thing was your walking. Regardless of whether or not you were any good otherwise, you had to be able to walk naturally in front of an audience. That is harder than it sounds. This also took me two years to learn. There was also ballet, vocal music, classroom lectures… I only got to speak my first lines in my third year there.

Friends at the Haiyuza Training School

Nakadai is second from the right in the front row, with Sato Kei to his left

Having their students thoroughly learn these kinds of fundamentals for three years surely brought desired results. Beginning with Nakadai, the Haiyuza Training School produced numerous great actors. There was Ozawa Shoichi two generations above him, there were his generation-mates Utsui Ken, Sato Kei, Sato Makoto, and Nakatani Ichiro, and his juniors include people like Hira Mikijiro, Tanaka Kunie, Igawa Hisashi, Narita Mikio, Yamazaki Tsutomu, Kato Go, Harada Yoshio, Natsuyagi Isao, and so on.

They were training us hard every single day. That must be the reason why we were all able to work as professional actors as soon as we graduated. Professionals will remain professionals until death—that’s why it’s so important to first know your fundamentals.

We had amazing instructors—we’d regularly see people like Yoshida Kenichi and Kinoshita Junji coming in. But while our lessons in practical skills finally began in my third year, most of the time they would call for us by our names in alphabetical order. Thus, it would always be the “Abes” or the what-have-yous to go first—I’d be waiting for my turn forever and they still wouldn’t get all the way to “N.” I would literally get into fights with those “A” people because they were annoyed about “having to go first again.” I’d be yelling, “so then switch places with me, dammit!” But of course because the instructors would be different each time they didn’t know about any of this. So I would always be stuck there waiting for my turn which would never come. Because of this, I hardly ever received any actual acting training.

I was friendly with everyone, but the truth is that at the end of the day we were all in competition with one another. A person by the name of Aoyama Sugisaku was our great master, and when the fifty of us first got into the training school he said he “felt sorry” for us. That was literally his message to congratulate us. “Only one of you will get to join Haiyuza—the other 49 of you are basically paying your monthly tuition fees for the sake of that one person.”

Only one of us would get to become an actor. That meant it was me versus 49 others—I had 49 rivals. I etched this into my mind. That definitely became the source of some fighting spirit for me.

I watched a lot of plays, even if they weren’t always to my taste. As for films, that was right around the time of Marlon Brando’s golden age. I watched Elia Kazan’s On the Waterfront many times while thinking to myself how he was the kind of actor I wanted to become.

That’s how I would learn in the beginning: by watching. The instructors didn’t teach us anything. Acting is all about watching and learning—no one will hold your hand and tell you how to do it. I would always start by mimicking someone. If I heard someone on the train speaking in an unusual way, I would memorize the way they spoke. If I noticed someone using their eyes in an interesting way, I would stare intently at their eyes. That’s how I would build these mental images and try to pursue them.

Later on after starting my own acting school, Mumeijuku, I would only select around five people out of a thousand. So then this one time when I went to America, I got to meet with Lee Strasberg—the president of the Actors Studio—and I told him how I hoped I could make at least one of those five into professional actors within a year.

His reply was, “Mister Nakadai, you are much too naive. This world would go to ruin if there were that many new actors popping up. Just try to produce one new actor every ten years.” And I said, “Oh, I see… So I shouldn’t be aiming to debut one new actor a year?” “Absolutely not,” he replied. And he was right. I have been running Mumeijuku for 42 years now, and there are only a handful of students of mine who now make their living solely through acting.

In his training school days, Nakadai was especially close with his acting buddies Utsui Ken and Sato Kei.

Utsui was one of my last surviving generation-mates. We would often talk on the phone before his passing. He was such a joyful man—the exact opposite of people like me and Sato Kei.

He had been a star player in Waseda University’s horse-riding club, but he then made made the switch to acting. None of us had any money back then and we couldn’t even afford the train fares, so everyone would be jogging from Shibyua to Roppongi which is where the training school was. But not him. He was the son of a family who owned a ryotei restaurant, so he was very flashy.

I first met him at the training school during the announcement of the results of our audition. I had been trembling in the knees so badly at the first stage of exams that I didn’t even go to that announcement because I was sure I had failed. But somehow I did pass, and now I’d made it all the way to the third stage. I remember reading the results of that third exam when I noticed a man standing next to me wearing this super flashy sweater. It was Utsui. He asked me if I had passed, and I told him yes. When I did he embraced me, and as we were locked in that embrace we both started jumping up and down in joy.

Nakadai’s Haiyuza buddy, Utsui Ken

Sato Kei was four years older than me. He was in Haiyuza’s production department when I first entered the training school, but he switched to acting and that’s how we got together.

In those three years, I failed a movie audition nine times—as did Sato. We were both so shy and withdrawn… I guess we should’ve just tried to smile more, but we couldn’t.

They would advertise movie auditions at the training school, and many different directors would come in looking for new actors. It was a rule that you were absolutely not to appear there as a first or second year student, but then in your third year you were allowed to have those movie directors see you. So basically, beginning in your third year you would start practicing real acting, and they would come and watch.

But people like me and Sato Kei, even though we really did want to act in movies, we were pretending like we weren’t interested. We took on this attitude of, “movies are lame—we’re only going to do theater!” Part of it was shyness, and I guess we just weren’t being honest with ourselves. Of course you’re going to fail when you have an attitude like that.

The first person to be chosen from my generation-mates was Taura Masami—it was for Shochiku director Kinoshita Keisuke’s film A Japanese Tragedy. The next opportunity was for a Shintoho film and with that one I actually made it until the very end stages, but they ultimately ended up going with my generation-mate, Utsui Ken. And just like that, me and Sato Kei went on to fail our auditions nine times… Looking back, it’s easy to see why. Me and Sato Kei—these two shriveled, young men, both of whom hadn’t taken a bath in a month, covered in filth, all skin-and-bones with our googly eyes… The two of us didn’t exactly fit the image of the kind of lively youth that the film industry was looking for at the time.

Joining Haiyuza

After spending three years at the training school, Nakadai officially became a member of Haiyuza and started properly on the path of an actor.

Eventually, having now experienced nine failures in a row, I was determined that I simply wasn’t meant to do movies. I was going to focus solely on theater. Me, Sato Kei, and another one of our generation-mates, Nakatani Ichiro, decided that Haiyuza had become “too outdated” and that the three of us were going to start up a new group. The plan was for it to be this new “Anti-Theater” type of thing. But then Sato Kei contracted tuberculosis and went back home to Aizu, dropping out. Eventually the rest of us also decided that it’d be no use, and that was the end of that particular dream…

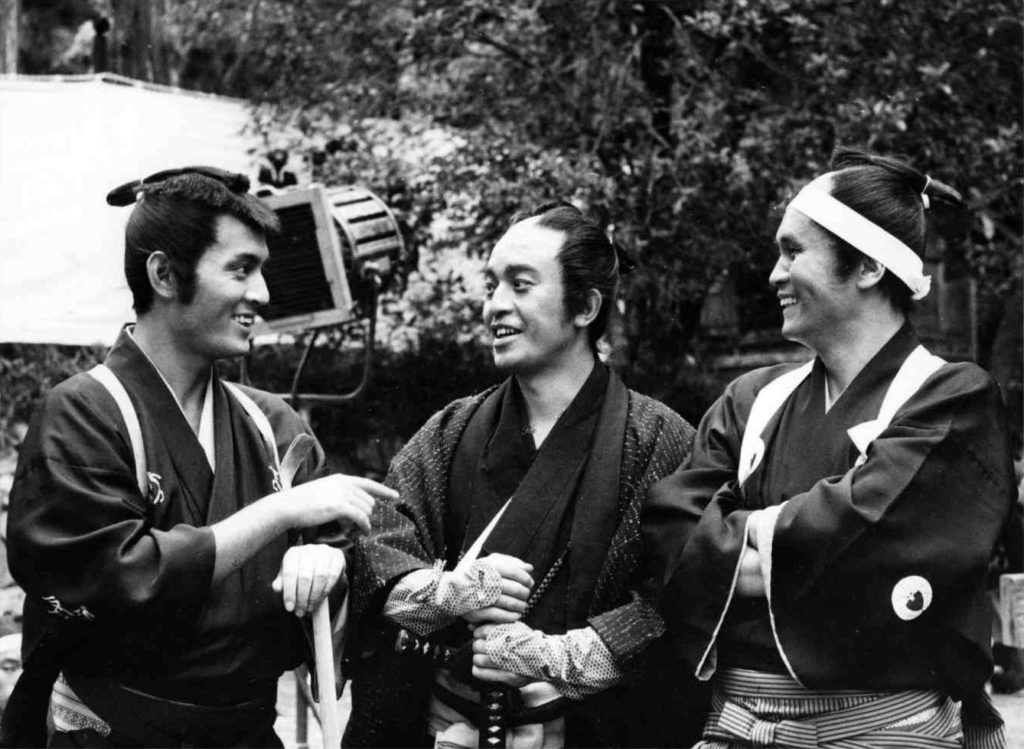

Friendly chatting between takes: (L-R) Nakadai, Sato Kei, Nakatani Ichiro

On the set of “The Sword of Doom,” 1966

But then, me and Nakatani Ichiro—just us two—were happily selected, and we got to join Haiyuza as research students.

Right around this time many of Haiyuza’s young talent left the group in one fell swoop to start a new troupe called Seinenza. Suddenly all the young people were gone—this meant that I could now get my foot in the door.

The year after I became a member, I managed to score the role of “Oswald” in an Ibsen play called Ghosts. The famous actress Higayashiyama Chieko played the role of the mother, and my teacher Senda Koreya was the pastor.

I had around a hundred seniors in those days, meaning that whenever we finished a performance I would receive criticism from a hundred people. And no matter how many times we did the play, I would always be criticized. But as it just kept happening, I found myself thinking… “Huh?”

Basically, there were some actors there who had been acting for twenty years and they had never so much as received a single line. And suddenly here I was, this young guy who had received this great role out of the blue. Of course I was going to get bullied. Mind you, I still heard them all out, but in doing so I became able to tell which of them were just picking on me and which of them were actually giving me sound advice. I became selective about which words of advice I genuinely took to heart.

Mentor, Senda Koreya

In Haiyuza the person Nakadai most revered was his mentor and superintendent of the troupe, Senda Koreya.

When I first joined the training school, Senda told me that I had “no sense for literature.” I was supposed to be an actor, and yet apparently I had zero sense for literature! What did he mean by that? I kept thinking about it.

What I realized was that when it comes to acting, having a “sense for literature” means being able to interpret the drama. Take Shakespeare, for example. What was he trying to say with any given play of his when he wrote it? Actors have to understand that first, even if just conceptually. With movies, too, it’s the same thing with the original work or the script. It’s only once you understand it that you can start to think about things like… “If my role was a color, what color would it be? What sort of a voice should my character have when he speaks?”

As Ibsen once said: “there is no better liar than an actor.” It’s all about how you can best make what you’re saying sound as truthful as possible. For instance, when you’re doing your lines you don’t just memorize them and say the words. Rather, you make it seem like you yourself are coming up with the words on the spot as you’re saying them. That’s something I was always told even back in those days. But of course, that’s easier said than done.

That was all Senda’s influence. I stuck by his side for a long time, you see. When we did Hamlet for example, even during the scenes where I didn’t appear I would still be at the wings of the stage, staring fixedly at his acting.

Nakadai’s acting mentor, Senda Koreya

Nakadai’s acting mentor, Senda Koreya

Senda did both acting as well as play producing, but later he mostly came to do just production. Thus, I’m sure there are lots of people who only knew him as a producer and never as an actor. But for me, the way I speak for instance? It was all influenced by Senda.

When my sensei got on stage, the entire atmosphere in the room would change. People like to talk about someone “having a presence,” but that’s actually something that is difficult for us actors to tell when we’re acting. Senda would often tell me, “Nakadai, you have to make a complete change from the moment you step on stage.”

It’s like a hundred meter run—the athletes all raise their backs with the “set” in “ready, set, go.” While there’s nothing quite as obvious as that when it comes to acting, you still need to kind of get into the right mindset in a similar fashion.

And in order to do that, what you need to do is study. That was my sensei’s theory. He was especially adamant about always learning your co-actors’ lines first. Doing so, you become able to really hear the other person’s lines, and you’ll be able to say your lines naturally when it is your turn.

It’s the same with movies. It’s important to be the “receiver” when acting by reacting to the other person’s lines, but in order to do that you need to know their lines, too. If you can’t receive you won’t be able to attack either. Manzai comedy has the “straight man” and the “funny man,” but when acting you should be able to do both. Even if you’re the one doing the attacking, you won’t be able to do it well if you can’t receive, too.

The person who taught me about the importance of “receiving” was the famed actress Yamada Isuzu. “Learn all of your partner’s lines. Learn them before you even learn your own.” Learn the other person’s lines, listen to them carefully, and express yourself accordingly. It really was a wonderful lesson to learn.

I later spent two years at the Abe Kobo Studio, and even there I was constantly learning about “receive acting.” When you’re doing improv you have no idea what the other person is going to say, so first you have to listen in order for you to be able to do anything. Once again, this speaks to the importance of “receiving.”

The baseball player Nagashima Shigeo would often take risks in his batting. A reporter once asked him why he did so. This is how he replied:

“I swing my bat a hundred times more than anyone else. By doing so, I know I’m going to succeed when I take that chance.”

It’s the same thing with acting. I strongly believe that practice and the actual performance are but two sides of the same coin.