Naruse Mikio, Kinoshita Keisuke,

and the Actresses

No matter whether it’s contemporary or historical drama, people often tend to associate Nakadai Tatsuya with roles that are somehow eccentric or extreme in personality. One director who always utilized Nakadai in portraying very ordinary people, however, was Naruse Mikio. Best known for his art films such as Floating Clouds and Repast, he is one of Toho’s representative directors.

Focusing especially on his works with Naruse, in this chapter we asked Nakadai to tell us his stories of some of the actresses he has co-starred with.

Meeting Naruse Mikio

Even before becoming an actor myself, I had always found happy endings boring.

All the Hollywood movies back then had happy endings. French movies, on the other hand, would all end with the protagonist dying or something to that extent, so you would leave the film theater feeling all gloomy. Those are the kinds of movies I like. Even when considering my own work, out of the 160 films I’ve been in, I must’ve died in a hundred of them. I’m always killed off! I personally think it’s just more fun to do roles where I die—that’s why the role I’ve done the least is that of the salaryman. Even the role that I was first acknowledged for was the violent thug I played in Kobayashi’s Black River.

However, one early role of mine that was a bit different was in Oban, starring Kato Daisuke and based on a novel by Shishi Bunroku. Kato played “Gyu-chan” who was this intense stockbroker, and I was the friend, “Shin-don.” I’d be going, “Gyu-chan, please don’t resort to violence!“—the reserved, ordinary guy trying to put the breaks on the wild protagonist. There was this film critic called Tsumura Hideo, and when the movie came out he called me a “wonderful new actor.” That role was what led to my roles with Naruse.

While I played these strong characters for directors like Kurosawa or Kobayashi, that role in Oban was quite close to my true self. Naruse must’ve accurately picked up on the character’s “guy who does nothing” element in my real self, too.

Director Chiba Yasuki’s Toho film Oban became a hit series spanning four movies from 1957 to ’58. Involved in the planning of the project was Fujimoto Sanezumi, a senior producer in charge of Toho’s film productions. He had also worked with Naruse Mikio on most of his films, and immediately after the first film in the Oban series, Nakadai appeared in Naruse’s Untamed owing to Fujimoto’s recommendation.

Untamed is a love-hate relationship drama between a married couple, played by Takamine Hideko and Kato Daisuke, who run a cleaning business. Nakadai appears near the end of the film in the role of a young apprentice at their shop.

Fujimoto seemed to have always acknowledged me ever since I was young. He’s the person who first handed me the script for Untamed, asking me what I thought. I thought it to be very interesting, and as I’d seen many of Naruse’s films in my teens I asked him to let me do the role.

This is something I heard from Fujimoto. Having gone on to appear in more of Naruse’s films after that first one, he apparently spoke about me to Fujimoto. “As an actor, when Nakadai appears in the films of directors like Kurosawa he comes across as so intense and aggressive. But in my films he’s surprisingly good for his age at just receiving.” Hearing this, it only further convinced me how Naruse preferred acting that wasn’t theatrical. When I was appearing in his movies, he often told me to “just keep motionless as much as you can.” He’d tell me, “I know you were a shingeki actor. And I guess you still are. But don’t act that way in my movies.”

Being a shingeki actor, I’d decided that I was going to spend half of each year doing theater and the other half doing movies. Theater actors tend to think that the more you can just go all-out in your acting, the better. When a theater actor gets to be famous, he starts to think about things like how the audience perceives him; how he can look his best. They fall under the illusion that if you just go all-out in your performance, the audience is automatically going to appreciate whatever you do.

But when I started appearing in movies, I realized how what I wanted to convey through my acting wasn’t at all coming across on the big screen. In that sense, I’m glad I decided early on in my youth to split my time between the two arenas. People often ask me, “What’s the difference between a theater actor and a film actor?” The answer is that they’re the same. They’re the same… but in theater you just can’t see yourself objectively.

I believe what Naruse was trying to tell me was to not act in such an exaggerated way. Shingeki actors at the time must have been performing the same way regardless of whether it was on the stage or in movies, and while they were good at it, it was a “manufactured” kind of acting. I think what Naruse wanted instead was realism. The sort that an amateur actor might possess.

The first time I met Naruse he told me, “I don’t need any fancy technique from you. Act as tacitly as you possibly can. You just stand there. I’ve seen how you act with Kurosawa—don’t act in such a grandiose way in my films.” Kurosawa was more theatrical compared to Naruse. But the thing is, Kurosawa actually very much respected him. “The director I most respect is Naruse,” he would say. “And Ozu after him.”

Acting With Takamine Hideko

In all of the Naruse-directed films in which Nakadai made an appearance, he always co-starred with Takamine Hideko. Having starred in most of Naruse’s works since Floating Clouds, as well as in films like Twenty-Four Eyes and Carmen Comes Home, Takamine Hideko appeared in numerous works which symbolize the Golden Age of Japanese Film—an actress representative of the entire era.

I was born in 1932, and all the boys who were born just a little bit before me in 1930 or 1929 became soldiers. So, so many of them died. As a result there weren’t many actors from that age group, and indeed, one of the reasons I was picked for roles in my youth was to fill that hole.

When I first made my debut in my twenties, nearly all of the actresses playing opposite to me were older. Aratama Michiyo was two years my senior, while Awashima Chikage and Takamine Hideko were eight years older. I was thus always filled with trepidation acting with them.

Takamine had been acting in films ever since she was a child, so she was obviously a great senior of mine. I had already seen her in many masterpieces such as Floating Clouds prior to working with her, so I really felt like just another fan of hers when I was to act with her for the first time. I was so excited. My heart was beating like crazy.

She was an exceedingly rare case in terms of Japanese actresses in how she was capable of portraying such an intense sense of nihilism. That kind of… womanly obstinacy, if you will. While it was of course something that only made her the better for it, she wasn’t merely “beautiful” or “pretty”—she was an actress who had erased all that “cuteness” about her. She revealed the true of essence of women in her acting. Also, she was just so excellent at portraying that sort of “listlessness.”

The first time we met was during Untamed, and she would go on to teach me so much on set.

There is this shot where I’m smoking a cigarette. It started with a distant shot, then there was a cut, and next it was to be a close-up. Initially I was holding the cigarette near my waist, but in the next shot it was to be a close-up of my face. I was just speaking to myself, wondering where I should be holding my cigarette. Takamine overheard me and said, “What are you going on about? You don’t need the cigarette anymore when the camera’s that close. Hold it if you want, I guess. You should know this stuff by now!”

She continued. “You know, I don’t like you theater actors. You put too much feeling into it.” I asked her what she meant. “Films are like puzzles in how they’re assembled from many different scenes. With you theater people, when the curtains open you go from act one, to act two, to act three—it’s all in order. With movies, you could start by filming the very last scene first. That’s why you always need to know how much or how little feeling you need to be putting in. I know you theater people look down on us film actors, but just so you know, being a film actor is so much more draining.”

But then she was also so kind towards me the first time I went overseas. Takamine herself had taken some time off in France, and so she told me about all the best places to go in Paris and that sort of thing. She even gave me a farewell gift.

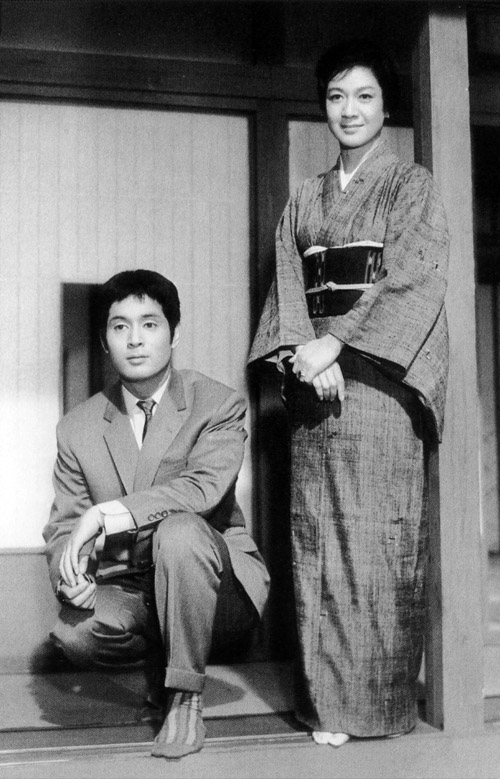

Takamine Hideko and Nakadai in “When a Woman Ascends the Stairs”

Looking back, because she had been a film actress for so long—since she was a child, even—I feel like she had a cynical outlook towards the film industry. There was just something different about her compared to your average actress. That’s how I saw her in any case.

She also had a very clear opinion as to what it meant to be an actor. She would say that actors are merely “something to be taken advantage of.” I’m unsure if that is how she truly felt. She could be a complex person that way. But it’s certainly something that may have contributed to her sudden retirement when she was 55. Maybe she felt that she had reached the limits of her abilities… Or rather, because the film industry was on the decline at the time, perhaps she felt it would’ve been no use sticking around in such an environment. She felt that it was a good place to stop. That’s what made her so wonderful as a person.

Someone once told me something that Takamine had said to them. “Nakadai is probably going to be the one carrying the entire film industry in the future.” Takamine told them, “He’s not just an ordinary movie star—he can actually transform himself for each role.” Of course, she would never say anything of the sort to me personally.

Out of all the films in which Nakadai and Takamine appeared together, one of the most memorable is Shochiku ace director Kinoshita Keisuke’s Immortal Love (1961). In this film—the complete opposite of Naruse’s work—Nakadai gives a fierce performance as an ex-soldier who rapes Takamine’s character and forces her to become his wife.

While Kinoshita made films like Twenty-Four Eyes, his body of work also includes things like A Japanese Tragedy and Immortal Love—I guess you might call them social awareness films. As an author, he had a kind of nihilistic mindset in a sense.

He was a man of strong hang-ups. Throughout his entire life, he never ate pickled vegetables. If by some accident any pickled vegetables appeared, there was going to be trouble. See, he was the son of a family that ran a pickle store and so he had been around the smells of those pickled vegetables since the time he was born. Never, ever have pickled vegetables around when you’re eating with Kinoshita—that was the rule.

There’s a story I once heard from Kurosawa’s script supervisor, Nogami Teruyo. There was a discussion between Kurosawa and Kinoshita in the Kinema Junpo magazine. Kinoshita said, “Everyone on my team always calls me “sensei” when we’re on set. But as soon as we’re done filming and we go to the bar, it’s all, “that big idiot Kinoshita!” Everyone starts trash-talking me.” Kurosawa was surprised. “Really? That’s how it is in your team? That’s not the case with my team! Right, Nogami?” Nogami could hardly say anything… She couldn’t even laugh. That’s just how much Kurosawa trusted people. But Kinoshita, he would always be silently observing everyone. That discussion really highlights the differences in personality between those two.

Takamine Hideko and Nakadai in “Immortal Love”

In Immortal Love, I play the role of a landowner’s son who goes out to war and comes back with a leg injury. There is a scene in the film where I hit Takamine in the face.

“Nakadai-chan”—that’s how Kinoshita called me. “Come here for a second.” He went, “This actress—she’s revolting, isn’t she?” Now, just so you know, she was actually Kinoshita’s favorite actress! And yet, he was telling me to hit her with all my strength. “Hit her with everything you’ve got. I mean, she’s just revolting!” I asked him to make sure. “You seriously want me to hit her? As hard as I can?”

And so we did the scene, I gave her a good smack, and it was a cut. So then Takamine, she says to me, “That hurts. You can’t act to save your life, but at least you hit like a man.”

I’ve done a lot of that sort of thing. Similarly in Black River, I punched Arima Ineko. Her face got so swollen after I’d hit her, and although she herself never said anything to me about it, the next day Shochiku’s then-president Kido Shiro got very angry with me. “What have you done to our star actress?! Who the hell do you think you are?!” Still, I didn’t even try giving him the excuse that it had actually been director Kobayashi Masaki who’d made me do it.

For some reason or other, I find myself having to hit women in a lot of scenes. And the directors all ask me to hit hard, too…

Acting With Hara Setsuko

In Naruse’s Daughters, Wives and a Mother (1960), Nakadai plays the lover of legendary actress Hara Setsuko, best known for her appearances in films such as Ozu Yasujiro’s Tokyo Story.

Simply put, in the world of cinema at the time, Hara was the holiest of the holy. As an actress, you could say she was almost mythical. That’s how we saw her. In my child’s mind, I remember thinking how you’d have your work cut out for you trying to find another actress anywhere in the world who looked as beautiful as Hara Setsuko did when she smiled. I appeared with her in Daughters, Wives and a Mother, and indeed, she really was just so beautiful.

I was something like her lover in my role. We were going to do a kiss scene when Naruse called me over. Being a quiet person, he was speaking only to me. He said, “Nakadai, do it for real.”

With kiss scenes in Japanese cinema, usually the way it works is you would embrace the other person, and then you would turn away from the camera so the viewers couldn’t actually see the lips connect. To actually have the actors kiss… It was something of a taboo back then. Especially with someone like Hara Setsuko—”The Eternal Virgin.” And so while I knew from reading the script that there was going to be a kiss scene, I figured we would be facing away from the camera as usual.

But now I had Naruse telling me to “do it for real.” I thought to myself, “Doing it for real… But that would mean our lips touching!” Hara’s manager then heard of this. “Our Hara has never done a kiss scene with actual contact. Do keep this firmly in mind.”

The director was telling me one thing and the manager another, so I went to ask Hara herself. “The director wants me to kiss you for real. May I do so?” And she said, “Sure. Do it.” I thought, “Oh, so she’s okay with it.” I can tell you that the manager was giving me some pretty serious stink-eye afterwards though. In any case, we did indeed kiss, and although I forget now how it was shown in the film, I still remember how my heart was racing whenever we were acting together because we had done that scene.

Nakadai and Hara Setsuko in “Daughters, Wives and a Mother”

When we went out to film on-location, she was drinking. She’s such an unreserved person. She went, “Nakadai, let’s gamble! What kinds of games are there?!” Back then, card games like dobon and 21 were popular. Awaji Keiko was with us, and so the three of us stayed up all night playing cards. I ended up losing quite a bit to those two—even though I was the one teaching them! I remember thinking to myself how terrible of an idea it is to gamble with women.

I didn’t yet have any money at the time, so when I got home and told my wife how much I’d lost, she went to the pawn shop or some such and came up with the money. The next day we were filming at Toho’s studios, and I immediately went and paid Awaji and Hara what I owed them—I think it was around 200,000 yen (USD$2000) in that day’s money. I remember the two of them praising me for how “manly” I was for doing so.

What Makes an Actress Attractive?

In regards to Toho’s star actress Aratama Michiyo, Nakadai starred as her husband in all six parts of The Human Condition, and later in Okamoto Kihachi’s The Sword of Doom.

All the actresses back then seemed to be coming from Takarazuka. Awashima Chikage, Arima Ineko… Most of Toho’s actresses, actually. Then there was also Aratama Michiyo—she was one of the old-timers, perhaps right behind Awashima in rank. A few years older than me, she was such a cheerful person.

Nakadai has co-starred with a great number of actresses throughout his career spanning six decades. From Nakadai’s perspective, what actually gives an actress her charm?

It’s rather difficult for one to be attractive both as an actress and as a woman. The thing about actresses is… Although this isn’t necessarily always the case, there’s an old saying that goes: “in this world, there are only men, women, and actresses.” There’s no such thing as “male actors.” Actors who are male are somewhat capable of compromise and more socially minded, meaning they will adjust themselves to the people and the situation around them—making them the same as the “average man.” An actress, however, is not the same as the “average woman.”

Let’s say you get a script and so you head into costume fitting. The director tells you, “This is your role, and this is what you’re going to wear.” Here, it is the actress who will say, “I don’t like that design. This is more to my taste.” They’re able to assert themselves, the thought of how it might inconvenience others never even crossing their mind. “No. I just don’t like this design.” As a result, no matter how attractive they might be as an actress they become less so as a woman.

Having seen things like that, it makes me feel like the actress is a completely separate creature.

In Mumeijuku, my acting school, I’ll notice certain women and think to myself how great it would be to see them become professional actresses. But once they graduate and go a year or two without making it big, not getting any roles in plays, they just run off and get married right away.

But all the great actresses? They do not seek any of the small happinesses in life, or the nice little family. This was true for Sugimura Haruko as it was for Yamada Isuzu, and as for Takamine Hideko, although she did marry she then retired after some time. They’re just two totally different things, the domestic life and the life of an actress. Observing the young women close to me, even if they continue acting after childbirth they will soon have those “mother’s eyes.” In that sense, I do think it to be tough to be an actress. Even Hara Setsuko, while I don’t doubt that she had romantic experiences, she never did marry.

The life of a great actress is thus marked by heroism. Hence: “men, women, and actresses.” Male actors will think, “If I do this, I would have to assert myself and inconvenience others.” Or they think, “I might cause offense.” But actresses—real actresses—don’t think like that. They do not hesitate, in a good sense of the word, to be as selfish as they please.

Thank you! I really look forward to reading these chapters.

Cheers! I’m making good progress on the next one, but that chapter is another long one so it’s going to take some time. I hope to have it up in April.

Thank you for this. If I may ask when will the next chapter comes out? 🙂

Hi Anon!

I should be getting Chapter Seven out around the end of this month.

Thank you so much! Just found your translation, and it’s just amazing to read this thoughts on Naruse and Takamine. I always had vague sense that Nakadai was a bit scared of Takamine (and maybe rather disliked her) but he couldn’t help but respect her as a fellow professional, and I guess this chapter confirms that, hahaha.

Keep up the good work!

Hey papaya. I’m glad you found my translation. It was definitely great getting to read about Nakadai’s thoughts on Takamine. When all is said and done, I think she might just be my personal favorite Japanese actress of them all. She was just such a pro. A real “actor’s actor.”