Expanding Overseas, Avant-Garde, The Left, Haiyuza Training School

The 1960s saw an uptick in student movements as counterculture became prevalent worldwide. Even in the Japanese film industry, anti-establishment-minded directors were producing one movie after the other, and for major companies at that. Nakadai himself appeared in many such works.

In this chapter, we asked Nakadai about the connections between those people and Haiyuza, of which Nakadai was himself a member.

Starring in an Italian Film

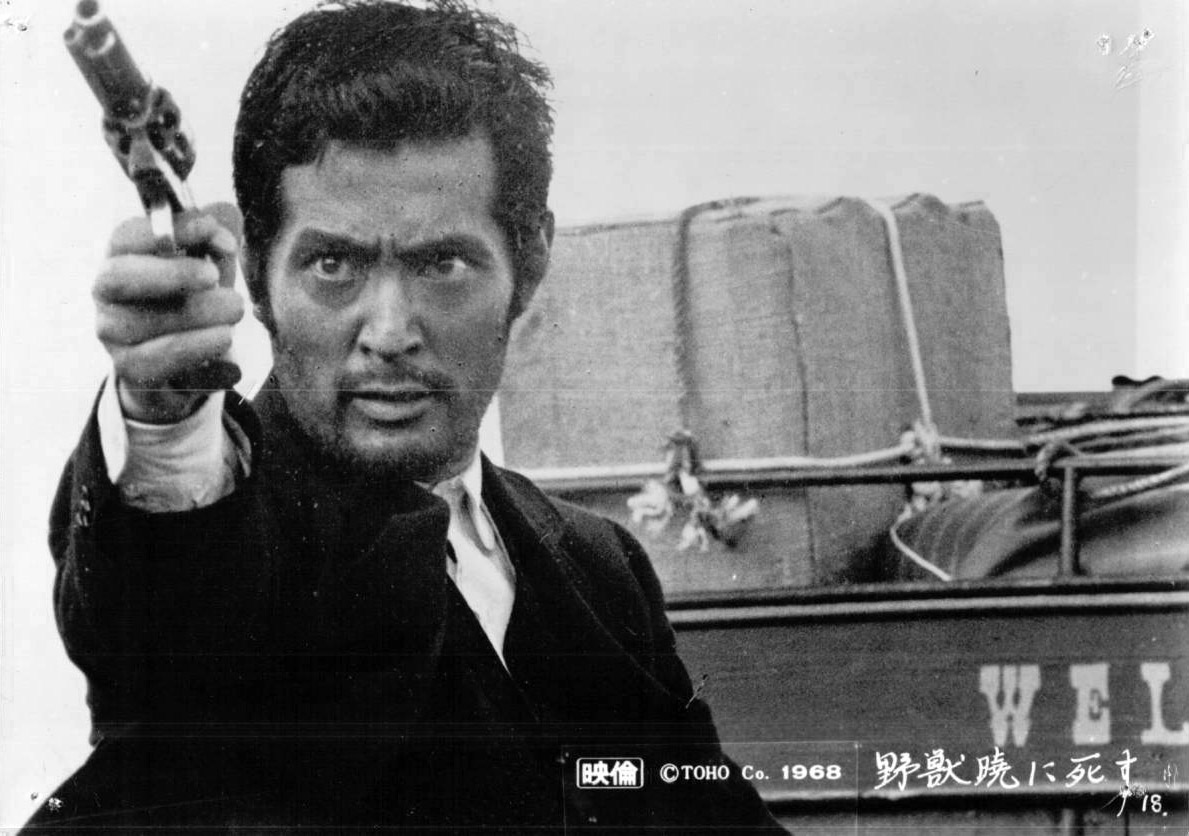

In 1968, Nakadai appeared as the villain in a spaghetti western (Italian western) called Today We Kill… Tomorrow We Die!

One day I got a phone call from Kawakita Kashiko at Toho-Towa, simply asking me if I wouldn’t mind going to Rome for a bit. I asked her what it was all about, and she just said, “This director called Antonio Cervi wants to hire you.” She told me she’d already mailed me the plane tickets so I should just go hear them out. I was sent first-class tickets, but as I was totally broke at the time I asked Japan Airlines to change them to second-class tickets so I could pocket the difference. But then because the director and everyone else were waiting to greet me at the airport in Rome, I had to ask the stewardess to let me de-board with the first-class passengers.

Once I got there, I had a meeting with the director. I asked him why on earth he needed a Japanese character for a spaghetti western. He went, “No no, your character wouldn’t be Japanese. He would be a mix of Indian-Spanish!” I was the villain and there’s this one scene where we attack a stagecoach. Riding a white horse, attacking a stagecoach… Having watched westerns in my youth, it had always been a dream of mine to be able to do that. That was my reason for deciding to take on the role.

Anyway, once I got to Rome, they sent out this luxury car complete with a chauffeur to come pick me up. Even my hotel was first class. I had about two weeks until we’d begin filming, so I spent that time practicing horse riding and my quick draw skills with the pistol.

I kept quiet on set because I couldn’t speak any English or Italian. Always just silently waiting for my turn. Meanwhile, the other actors would be talking about how they’d been out with this-or-that actress and all the rest of it. Suddenly the director yelled, “Shut up, the lot of you! Watch and learn from the samurai!” But in reality, I was quiet only because I couldn’t speak their language…

To this day I still can’t speak English, so for that film I just had to memorize all my lines. But the thing is that sometimes they would suddenly ask us to change certain lines on set, and it was simply impossible for me to learn new lines that fast when they were all in English.

So then the director asked me, “Well, how would you say these lines in Japanese?” So I told him how. “You bastard!” “What’re you talking about?!” And so on. So he said, “That’s fine. Say that, then. We’re just going to overdub the lines anyway.” See, Italian films back then would have two different people doing the acting and the voice acting. Regardless of if I was speaking in English or in Japanese, it didn’t matter because it would later just be dubbed in Italian anyway.

But then once we were done filming and I got back to Japan, Toho actually asked me to dub my lines in Japanese. Therefore, in that film, I first spoke my lines in my terrible English, then that got dubbed in Italian, then in Japan that got dubbed in Japanese by me. It was a strange sort of film that way.

Nakadai in “Today We Kill… Tomorrow We Die!”

Teshigahara Hiroshi & “The Face of Another”

Teshigahara Hiroshi was the son of the distinguished founding family of flower arrangement school Sogetsu-ryu. Adapting a great number of screenplays written by his close friend and author Abe Kobo—including Woman in the Dunes (1964), which won the Special Jury Prize at the Cannes Film Awards—his avant-garde style was highly praised worldwide at the time.

In 1966, Nakadai starred in The Face of Another. In it, he plays a man who, having severely burnt his face in an accident, begins wearing an elaborate plastic mask to cover it up—in effect making him “another.”

While Teshigahara was of course the son of the distinguished Sogetsu-ryu family, he nevertheless had a real passion for film making. And so after he graduated from arts college, he had his sights set on becoming a movie director. He started off working as an assistant director for Shochiku under Kinoshita Keisuke before eventually becoming a director himself.

I liked baseball around that time, even having a team of my own. The Shochiku AD’s also had their own team, and so we’d be playing at the outer gardens of Meiji Shrine once a week or so. It was right around this time that I first met him and realized, “Ah, he’s Kinoshita’s third AD. So this guy’s the son of Teshigahara Sofu of Sogetsu-ryu.”

Japanese artists back then used to all be leftists, but after the collapse of Stalinism they all left the Communist Party. Abe Kobo was in the Communist Party, as was Senda from Haiyuza—pretty much everyone was, really. It was right around the time of everyone’s withdrawal from the party that I first met Teshigahara. That was the impetus for me appearing in Abe’s Doreigari and other plays with Haiyuza, which then led to talks of The Face of Another.

Just about all of that movie was shot using hidden cameras on-location in Shibuya. I’d be walking around the area where the Tokyu Bunka Kaikan building used to be, my entire face completely wrapped up in bandages. We assumed that people would be staring at me, but instead everyone just tried their best to avoid me as they passed by. The hidden cameras worked to great effect. We’d have the occasional old lady pointing at me and such. But men would all avert their eyes. They must’ve pitied me. We actually wanted to capture more hustle and bustle, but everyone just kept trying to get away from me!

The way the film was shot was very avant-garde, and of course there was a lot of symbolism since it was Abe Kobo’s screenplay, but my performance itself was normal. The acting was the sole exception—the one thing about the movie that wasn’t avant-garde.

Rival, Hira Mikijiro

Hira Mikijiro plays the psychiatrist who makes the protagonist his mask. As a Shakespearean actor also from Haiyuza, he is often listed alongside Nakadai as one of the great actors of our time.

Like me, Hira had also been leading his own troupe in recent years. I always considered him a worthy rival. My feeling is that he thought the same of me as well.

At one time he was battling cancer and it almost took his life. I was very concerned and did what I could to help. After his recovery, however, it’s like he became defiant and started working even harder at his acting.

In the Haiyuza Training School, he was one year my junior. He, too, then joined Haiyuza and we appeared together in Hamlet. I was getting leading roles at the time while he was always a supporting actor. He then quit Haiyuza before I did and went over to Asari Keita at the Shiki Theatre Company. That was really when we parted ways, although that is not to say we got into a fight about it or anything of the sort. It’s just that since I was one year his senior in Haiyuza, the leading roles would all come to me. He saw this, felt that he wanted surpass me—and very much tried to—but then left Haiyuza before he really got the chance. But then he also ended up portraying “Hamlet” and things like that in Shiki, so it became a constant competition between us.

His way vocalizing his lines almost as if he were singing them at the top of his voice—something I also attempt to do now and then—was rare in shingeki back in those days. While kabuki and kyogen have different kata patterns and intonations that sound as if the actor was singing, shingeki doesn’t have that sort of thing. I feel like me and him were both individually trying to create something like that for shingeki, too.

He really was a hard worker. I was actually in New York at the time of his passing. I was getting phone calls from all sorts of media outlets about it, but since I wasn’t even going to be able to attend his funeral due to being overseas, it would’ve felt improper to just make a quick comment about it. Thus, I gave no interviews whatsoever on the matter.

Nakadai and Hira Mikijiro in “The Face of Another”

Ichihara Etsuko stars in The Face of Another as a mentally-handicapped woman who shadows the protagonist, giving a very realistic, eerie performance.

She was “Ophelia” when we did Hamlet with Haiyuza, having been handpicked for the role. She has just the most wonderful voice, and great intuition when it comes to acting.

Abe Kobo Studio

The screenplay for The Face of Another was written by Abe Kobo, similarly known for his avant-garde style. Nakadai became involved in the acting studio supervised by Abe himself.

After having written some scripts for Haiyuza’s plays, Abe formed an acting studio along with my teacher, Senda. Its training halls were underground, right where the Shibuya Parco Theater is located today. It was Senda who told me to go and study over there. Other actors like Tanaka Kunie and Igawa Hisashi would also be there, and later once the Haiyuza Training School ceased to be and became the drama department of Toho Gakuen, the graduates would all be there, too.

This was a time when I was receiving less and less interesting movie offers. I was just playing golf all day… I had kind of hit a wall as an actor. And so I decided to go there, seeking new stimulus.

Even though it’s something I don’t do at all nowadays, I was wholly devoted to learning improvisation over there. The setting could be, for example, a group of people who didn’t know each other, just waiting at some countryside station for a train that was taking its sweet time to arrive. Then, gradually, we would just start to have a conversation. I spent two years doing that sort of unscripted drama.

One time Abe asked me, “Nakadai, do you enjoy doing these plays?” I answered him that when people clapped at the end as the curtains came down, that gave me a sense of accomplishment—I had successfully kept the play going for yet another day.

“You’ve got it all wrong,” Abe said. “The ones clapping are people who just like “Nakadai Tatsuya,” the actor. And they’re going to clap no matter how terrible your acting might be. And the rest of them, they just clap because they get caught up in it—it’s just perfunctory. And those people, they’re going to keep clapping in the same perfunctory manner no matter how great your acting might be.” I thought to myself, “I see. So just receiving applause in itself isn’t anything to get excited about.” I felt like that realization really opened my eyes as an actor.

Miyazawa Rie’s Horse Fall

Later in the 80s, Teshigahara’s work became less avant-garde as he made a return to traditional Japanese culture in films like Rikyu. Starring alongside Miyazawa Rie, Nakadai appeared in Go-Hime (1982) as tea master Furuta Oribe, serving Tokugawa Ieyasu.

Woman in the Dunes, Pitfall, The Face of Another… He made some very avant-garde movies, but I feel like the death of his father and him having to inherit the Sogetsu school caused a bit of a change in how he made movies. Japanese tea ceremony and flower arrangement—Sogetsu was at the heart of all that, and with the passing of his father, Teshigahara succeeded him. Thus, he started looking at historical figures such as Rikyu or Oribe. I might add that both Rikyu and Oribe were artists of their time, and they too had politicians above them. At their core, I think them to be films about artists who are being crushed by the state.

For Miyazawa Rie, that film was almost like her debut work. Just to tell you a little anecdote about the film, there’s this scene where Oribe and Princess Go—Miyazawa—are running on horseback. She was taking the lead while I followed, but then she actually fell off her horse right into a gutter. She was sobbing, and Teshigahara immediately wanted to stop filming for the day. But I objected. “Director, if we don’t do this now, she’s never going to get on that horse again.”

The director asked if she would get on her horse once more, and this girl—she was only a teenager and yet so full of confidence—she just said “okay.” So we got on our horses, I took the lead this time, and we got the take. That was when I knew she was going to make it big.

Miyazawa Rie and Nakadai in “Go-Hime”

Yamamoto Setsuo

“Karei Naru Ichizoku,” “Solar Eclipse,” “Fumo Chitai”

Even as a more anti-authoritarian mood persisted throughout the 60s and the 70s, there were still many great works being produced by major companies, such as Daiei’s The Ivory Tower (’66) and Nikkatsu’s Men and War trilogy (’70-’73). Behind many of such smash hits was director Yamamoto Satsuo. Nakadai, too, starred in his films Blood End (’69), Karei Naru Ichizoku (’74), Solar Eclipse (’75), and Fumo Chitai (’76).

In his youth, Yamamoto Setsuo directed this movie called The Traveling Players, starring Tono Eijiro. It’s about this traveling theatrical troupe, and I appeared in it as well, still a member of the Haiyuza Training School at the time. I think I had about two lines in it. People often say that my role as the passerby in Seven Samurai was my first movie appearance… But while that may be true, my first role with actual spoken lines was in that Yamamoto movie. I played a young member of the labor union.

Now, Yamamoto, he was truly a man of social justice. Karei Naru Ichizoku, Fumo Chitai, and also Solar Eclipse and Blood End… Ultimately, most of my roles were characters who stood up against authority, like the protagonist in Karei Naru Ichizoku opposing his father; always fighting for freedom. The one exception was Solar Eclipse where I was on the side of the people with power. I got to do lots of different things with him. In that sense, he’s right up there with Kurosawa and the others in terms of people who were important for my career.

Having so little confidence in myself as an actor in those days, whenever I’d go to the film theater to watch a new movie of mine that had been released, I could only stare at myself on the screen, unable to focus on the movie itself. I’d think, “Ahh, I’m so terrible,” and just stand up and leave. Now that I’m in my eighties, I’m finally able to watch my old movies and think, “Hey, I wasn’t half bad there.”

Having been acting for 60 years now, I’ve become capable of looking at myself quite objectively as an actor. And not only as an actor, but as a person in general. I suppose that’s the best thing about getting old. Looking back on my films with Yamamoto, I’ll notice how I make a different kind of face when I’m playing the “man of justice” compared to when I’m playing the capitalist for example—my face changes according to the work. Not to say that I’m a “man of a hundred faces,” but yes, I have noticed that about myself.

As a director, Yamamoto hardly ever requested for me to do anything a certain way and instead just let me do as I pleased. I was expecting him to be rather strict what with him being as left-leaning as he was, but that wasn’t the case at all. While he did hold those ideologies, he was also extremely competent in the entertainment side of things—the way he could draw in the viewer.

Karei Naru Ichizoku is a film about the love-hate relationships between members of a zaibatsu family in which Nakadai plays the protagonist, the eldest son of the family. In the role of his father was veteran actor Saburi Shin, and together they gave an explosive performance.

Saburi Shin was just huge. He was part of what was called the “Shochiku Triumvirate,” and he was already a big star actor when I was only a child. Later on he also went on to do some directing. In Karei Naru Ichizoku, I collided with him time and time again and he’d just send me flying. He wasn’t much of a talker, and because he was such a great senior of mine I couldn’t exactly go up to him and strike up a conversation. But as soon as the cameras started rolling, I’d give my all as the son confronting his father.

But then he also had a strange side to him. There’s a scene where the family gathers around to eat at the table, but then when we finished filming in the evening there was still all this food left over, and Saburi ate all of it before going home. Also, he said he exchanged all his money for stones! I’m not sure as to the value of said stones, but in any case he said that stones were the only thing anyone would inherit from him. Apparently his whole yard was filled with stones. He took none of his assets to the bank—it all went towards stones.

Solar Eclipse deals with a story concerning a dam construction project and the corruption scandal surrounding it. Nakadai plays the Chief Cabinet Secretary, the evil mastermind pulling strings in the shadows.

That role was modeled after a real-life person: Kurogane Yasumi, the actual Chief Cabinet Secretary back in the day. This person… He was a bad man, and yet he had this softness about him. That quality—like a strange kind of “nobility”—was detailed in Ishikawa Tatsuzo’s original novel in great detail. So I took that and further emphasized my own softness, trying to come across almost as feminine and pushing it so far as to seem unpleasant. That, on top of his overly polite demeanor…

In straightforward movies the villain acts like the stereotypical villain just as the righteous man acts like the stereotypical righteous man. But in this day and age, little by little the whole idea of “good and evil” has become less trendy. People are multifaceted—you put a person in a certain set of circumstances and they will undergo a complete change. It’s a very Stanislavskian concept. “Always portray people in a multilateral manner.” It was the perfect role for that sort of thing.

I liked that role. I suppose the reason I jumped on it right away was exactly because I’m such a twisted person myself.

As with Karei Naru Ichizoku, Fumo Chitai was based on an original novel by Yamasaki Toyoko. The film depicts a dispute between trading companies who are competing to provide Japan’s Self-Defense Force with fighter aircraft. Nakadai’s role as trading company man “Iki” was modeled after Sejima Ryuzo who rose to become the chairman of Itochu Corporation.

I had the pleasure of meeting Sejima on several occasions, and he was always very kind to me. From his internment at a Siberian detention camp, to coming home and working for Itochu and buying aircraft from Americans… He lived an immense life. As I am an actor I can’t claim to possess any great knowledge on the matter, but my feeling was that when corporations like that hired new people, they would’ve had to have been someone who had, through college, come to fully believe in something like Marxism at least. They wouldn’t have made for very good capitalists otherwise.

“Iki” experiences being a prisoner of war, comes home, and becomes an entrepreneur. Those exchanges with the Americans in regards to aircraft—which I believe is something of a reference to Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei—and just his constant worrying over so many things both during and after the war… It was a very interesting role to play.

Shingeki Theater and the Leftist Movement

As was often the case with films of people like Teshigahara Hiroshi and Yamamoto Satsuo, a great number of shingeki actors appeared in the works of directors with anti-establishment beliefs.

Shingeki theater was originally this thing that went against kabuki, kyogen, shinpa, and other old forms of theater. It’s as if they were saying, “This is what modern-day theater looks like!” That is the sort of thing that people like Tsubouchi Shoyo and Osanai Kaoru were actively trying to promote. I believe the first real shingeki—with kabuki actors—was done by Ichikawa Sadanji II. It was done in an “anti-Japanese theater” manner so to speak, as they started introducing to Japanese audiences the great foreign works of people like Shakespeare and Ibsen.

But while all of that was going on, Japan’s involvement in the war was getting deeper and deeper. Now, at the time, shingeki itself was a minority. If you were to do a play like Gorky’s The Lower Depths, for example, the censors would be all over you because the word “freedom” appears in the script. It would then get erased, just like with censored words in novels. Everyone in the shingeki scene had to struggle through that together, and so as a result I do believe they shared a left-wing ideology.

During the war, most of the important theater people—in other words, the ones with left-wing ideas—were put in prison. Even my teacher, Senda Koreya, was imprisoned. So they had all these people behind bars, but then the war ended and they let them all out. Communism and the Communist Party as a whole were on the rise. This was around the time that I joined Haiyuza, and well, you could’ve basically called it a left-wing troupe. Then the Toho Dispute happened, which was basically all about Toho’s Labor Union seeking freedom to make the movies they wanted, and Toho wound up bringing occupying forces to their premises. Toho’s union leader at the time was Miyajima Yoshio, the cameraman for The Human Condition, and the biggest symbol of the movement was Yamamoto Satsuo.

Most of the people in Haiyuza were left-wingers as well as members of the Communist Party. That’s how so many of them came to collaborate with Yamamoto Satsuo on his film productions. But the thing is that if you were a known member of the Communist Party, major companies like Toho and Shochiku wouldn’t give you any work. And so afterwards even in the age of free thought, people still kept it hidden—everyone wanted to work for the major companies.

Another Mentor, Ozawa Eitaro

In Yamamoto Satsuo’s films at the time, one actor who played one unpleasant, influential character after the other—often becoming a target of the audience’s hatred while doing so—was Ozawa Eitaro. On many occasions he stood in the way of Nakadai’s characters as well. In Haiyuza, however, the two actually had a teacher-student relationship.

Prior to becoming an actor myself, I saw this film called Desertion at Dawn by director Taniguchi Senkichi which starred Ozawa as the villain, and he was just so great. I could say the same about his performance in The Human Condition, too. Without someone like Ozawa, it’s difficult to fully portray evil on the organizational level. You see, he could do two things at the same time: portraying an individual wickedness as well as a proxy for structural evil. That’s the kind of actor he was—he acted in a way as to be symbolic of evil as a whole. And I believe he enjoyed doing so, too.

In Haiyuza, Ozawa was my teacher. He was a great stage director, too. I played “Iemon” in his directorial work of Illusion of Blood. While it was a shingeki play, we did it based entirely on the kabuki script. Everyone from Nakamura Kanzaburo XVIII to Sugimura Haruko came to see the opening day performance. A shingeki actor doing kabuki, especially in the role of “Iemon,” was quite a big deal at the time. But for me personally, I actually found kabuki lines easy to do. It’s all in the seven-and-five syllable meter. “If you were to ask me why I love you so…” That’s not a shingeki line. It’s so rhythmical. The rhythm and tone is part of the form. “If you say you do not know, ah, then I shall tell you!” It just feels good to recite lines like that.

“No, I want to say it like this!” That urge that people have to speak in standard, stiff Japanese is something that hurts shingeki actors. Osaka dialect, Kochi dialect, all the Tohoku dialects… They are all a lot softer. When Tokyo was still called Edo, people there didn’t speak in the stiff kind of manner as they do now. Real Edo people—like the rakugo storyteller Shincho—the way they spoke had rhythm and a softness. But then something—be it Japan’s morals or something-or-other—got everyone speaking this current form of stiff Japanese. It’s something that really hurts actors as it does translated works.

There’s a certain aspect of theater I often find myself thinking about. Audiences go see plays because they are drawn by the actors. The truth is, however, that Japanese shingeki theater has never managed to break free from auteurism. Shingeki was born from the authors and the scholars, and so it always tends to tilt towards that direction.

I got to see a Broadway performance a while ago. The story itself wasn’t very interesting—it was a musical—but their technique was amazing. Their technique, the fast-paced tempo, and just the sheer talent of the actors… Amazing. So my hope for the next generation of shingeki actors is for them to hone their skills in a better way. There was a time when shingeki was considered a means of delivering ideology to the audience, but that is not it. Shingeki is about technique.

Okada Mariko and Nakadai in “Illusion of Blood”

The shingeki we were doing back then was mostly Japanese-translated works, but Ozawa Eitaro went against that by wanting to do full-on kabuki. And so I’d have to have my entire body down to my legs painted white. The reception I got was that I was apparently a “handsome new tsukkorobashi actor.” I asked my seniors. “What does that word mean? Tsukkorobashi?” They explained it to me as “someone who looks handsome even when he’s being thrown around all over the place.” That’s what the word means. Apparently, Sugimura Haruko made a similar comment about me to someone. “He’s not much of an actor, but at least he’s pretty. He’s got nice legs.” She’s another person who taught me a lot.

As a child, I was so quiet and I cried so rarely that my mother was actually worried I might have a stutter. Even after I grew up I still never spoke much, and when I do speak I do so very slowly. Having lost my father so early, the people around me were always relying on me and so you might say I struggled with showing emotion.

I joined Haiyuza after first having spent three years at the training school receiving basic instruction, and to some extent Ozawa had always acknowledged me from the very beginning. But then one day he just said to me, “You. You need to speak more.” He gave me some words of advice in regards to that. People like to think that “silence is golden” is supposed to be some holy characteristic of Japanese men. There was also that whole “a real man shuts up and plays the game” commercial. But that’s all wrong. Even if they’re perceived as being shallow, an actor should always be chattering on about something. That was what he told me.

From that point on, I did my best to become more talkative even if it was only to say something totally pointless. I would commute from my place in Hatsudai to Haiyuza’s building in Roppongi, and when I was on the train—while it’s embarrassing to admit—I would be shouting, “I’m an aspiring actor! I’m now going to recite some lines, so please listen!” And I kept doing that for two whole years. But I did become better at expressing myself through doing so. Finally, in my fifth year at Haiyuza, Ozawa said to me, “At last you’ve become able to speak, huh?”

The moral of the story is: no matter what it is they’re saying or how they might be perceived, actors need to speak. Of course they do. It’s a speaking art, after all.

However, most of the time he would just be terrifying, Ozawa would. If you were even a minute late to practice, he wouldn’t let you get up on stage at all that day. My seniors back then were all dreadful like that. See, I was playing it both ways: movies were where the money was, while theater wasn’t earning me a dime. So my seniors would be saying, “Going out there to make some bank, huh?” I would tell them that this wasn’t the case. They’d warn me, though. “Having too much money will hurt your acting.”

I was actually glad they told me that. While I’m sure part of it was just them teasing me, what they were saying was nevertheless the truth. When you’re working on your passion, just barely making ends meet when suddenly you come into some money, it’s kind of… You can’t help but become a little less earnest about what you’re doing.

I’m the kind of person who can’t take praise. It’s being disparaged that motivates me. When my wife passed away around 20 years ago, the shock was so immense that I was ready to quit both acting as well as Mumeijuku altogether. Right around that time, I had been doing Richard III and it had gotten a good reception. But there was this one person who said, “Ahh, Nakadai’s past his prime. Just an actor whose best-before date has expired.” When I heard that… I felt so inspired. It was those very words that caused me to make a comeback.

That person is still around today. I should give them my thanks.

Haiyuza’s Connection to the Film Industry

In the Golden Age of Japanese Film, Haiyuza actors were making constant movie appearances. Their leaders such as Ozawa Eitaro, Tono Eijiro, and Mishima Masao often appeared as villains or minor characters in both period and contemporary drama alike, while their young talent—Nakadai, of course, and actors such as Tanaka Kunie, Hira Mikijiro, and Nakatani Ichiro—were also making frequent film appearances. It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to say that Haiyuza were sustaining the entire film industry at the time.

It was all because Haiyuza couldn’t survive doing just theater. Especially because they’d borrowed money from these high-interest loan sharks for building their own theater. It was a very large amount of money they owed. That was right around the time I joined. Their building in Roppongi even had to close up shop at one time. Then, when it was time to build it anew, the people from Haiyuza—Tono, Ozawa, Senda, Mishima Masao, and many other seniors of mine—were all thinking about how they could pay back their debt.

But even setting all of that aside, we were all appearing in films just so we could keep doing theater because, like I said, theater didn’t pay. In other words, many of us saw film acting as a side job. To people who had been doing theater for decades, movies must’ve felt like nothing. All those new faces appearing in films could never recite their lines properly, so they’d have to rely on us shingeki people. If you watch the films of directors like Yamamoto Satsuo you’ll notice it’s practically all actors from a shingeki background, including the young ones.

I was the first one of us to become serious about movies. I didn’t see it as a side job, but I didn’t abandon theater either. I split my year in two: one half for movies, one half for theater. Let’s say I was set to do a theater play in the role of a passerby. Just then, even if I’d get an offer to do the leading part in a movie, I would absolutely choose to turn it down and keep doing the play. The reason I did so is because I knew that if I didn’t, my acting would get sloppy.

So although I was doing theater, I never thought of movies as a side job. I’m certain that most of us did though. Everyone was appearing in movies just to make money for Haiyuza to pay back their debts. Even me, I would give 70% of my movie performance fees to the troupe, pocketing only 30%. The other actors would tell me, “Just think of the 30% as having been your whole fee to begin with.” I just thought, “Well, okay I guess… If you say so…”

Producer, Sato Masayuki

Beginning with Karei Naru Ichizoku, one person whose name often appeared in the credits as the producer of productions featuring Nakadai was Sato Masayuki. He was Haiyuza’s point of contact, managing all of their actors’ film and TV appearances.

The fact that I am where I am today is thanks to a combination of good fortune and various other factors, but one of the biggest things was having made my acquaintance with so many directors and their works. For some reason I happened to get accepted into Haiyuza and become an actor, and when I did I started receiving offers from the film industry, too. In those instances, the person who mediated all of that was none other than Sato Masayuki.

As a matter of fact, I got an offer to do the leading part in a movie the year I got into Haiyuza. It was this thing about a human torpedo… But upon reading the script I was just disappointed by how lacking it was compared to foreign cinema. And so while I was hardly even making enough to eat, still working at a pachinko parlor, I actually turned down this offer for a leading part.

Sato approached me about it. “What are you thinking? This is a leading part. It may be a dull movie, but still—it’s a leading part!” Apparently I then said to him, “I’d rather do a supporting role in a movie that’s actually interesting.” Mmm… I was a headstrong young man. But to his credit, Sato gradually came to have my back. I have appeared in over 150 films, but I have actually had scripts sent to me for over 300. In other words, I’ve turned down approximately half of all the offers I’ve gotten. And the way Sato handled the rejections was not by telling them how “Nakadai doesn’t want to do this film,” but rather by saying, “I’m making the call that I can not have him appear in your production.”

Sato was originally a screenwriter, and he was in Manchuria during the war. In trying to turn it into Manchukuo, a vassal state for Japan, they had created things like the South Manchurian Railway as well as Manei (Manchukuo Film Association). Lots of movie folks went over there to work for Manei. But then when the war ended, all those same people who had been making movies in Manchuria came back to rebuild Japan’s film scene. Sato was one of the central figures in all of that. But then for some reason, during the postwar period he became the chief of Haiyuza’s Movie Broadcasting Department.

It’s thanks to him that I’ve been able to have such a long acting career; that I’ve been able to enjoy a better-than-average life as an actor. With your typical manager, the conversation would be… “I don’t want to do this movie.” “Come on, don’t say that. They’re going to pay us good money. It’ll be for Haiyuza’s sake, too.” But with Sato, if I told him I didn’t want to do a certain movie, he would simply draw on his cigarette and he’d say, “Yeah.” That’s all. To the movie companies he would just say, “Nakadai can not appear in your movie due to various circumstances.” So he was almost like a father to me. His wife, by the way, was actress Sugai Kin.

Therefore, it would be impudent of me to claim that I’m solely responsible for everything I’ve accomplished. It’s all thanks to the people who watched over me; supported me. That’s why I could always remain rather selfish. Of course, I always gave it my all when we began filming. But I was selfish when it came to actually choosing the works I wanted to do.

With movies, you don’t get to do the exact roles you want. You only get to choose from the offers that are given to you. Times like that, I would look at five scripts or so and pick the one that seemed the most interesting. But the key is that I made it so that at that stage I wouldn’t know how much the pay was for each project. Why? Because the promise of a huge pile of money can make even a boring script seem enticing.

Instead, I’d have them tell me at the end of each year. Oftentimes what would happen is that I’d go, “What, I only got that little?! What about that other movie, the one I turned down?!” “That one would’ve paid ten times as much.” Just for an instant I would think to myself, “Dammit. I have debts to pay. I should’ve just put up with it and chosen to do that movie instead.” But then I’d always tell myself, “No, that’s wrong. It’s not about the money!”

An actor’s profession is all based on supply and demand. It’s not a job where you should expect to get to only do what you want. And yet, for the most part I have been able to do just that. Thus, I do feel like my thinking made sense.

One actor who has appeared in a great number of films with Nakadai is Tanaka Kunie. He, too, comes from a Haiyuza background.

He’s simply someone you might call a great character. He failed the exams for the training school twice. It was his way of speaking which interfered with his success. He took his first entrance exam at the same time as me, for the 4th generation, where he failed. Then he tried again, this time in the same generation as Hira Mikijiro, but he failed again. He then finally got in with the exam the year after that one. So he’s three generations below me, with Igawa Hisashi being one of his generation-mates. He apparently worked as a school teacher while he was trying to get accepted into Haiyuza.

But then he finally did get in, and The Human Condition was the first thing we did together.

Nakadai and Tanaka Kunie in “The Human Condition II: Road to Eternity”

It’s that… That extraordinary character of his, beginning with his facial features and his unique way of speaking. I once said to him, “Kuni, if I spoke like you do, they’d reject all my takes. But when it’s you it’s like the director can’t tell whether it’s a botched take or if you’re just speaking normally. For you, it only adds nuance to your acting. I envy you.” He’s a very dear junior of mine.

In recent years, it has become less common to see actors who got their start in shingeki before finding success in movies. Nakadai is painfully aware of the harmful effect this has caused.

Looking back on it all now, it’s just hard to fathom the way we did things back then. You know, to this day the performance fees for actors haven’t gone up. We don’t have any unions either. While we would never do this in Mumeijuku, there are certain agencies who will happily try to get their new actors “out there” by offering them up to movie companies, asking for no fee at all. Or things like purposefully leaving actors hanging about in the vicinity of directors.

Today it’s surely the era of production agencies. Yoshimoto, Johnny’s, Horipro… They’ve now expanded their market even to theater. In the past, those positions were held by Haiyuza, Mingei, Bungakuza… But now, when someone on TV gets even a tiny bit popular, an agency like Horipro will gather up all those people and use them in starring roles for theater plays. And since of course they can’t project their voices, they have to use microphones even on-stage.

In this day and age, it has become difficult to make your way to the world of cinema or to the theater stage. Of course, a serious pursuit of acting is by default something that puts you in a crisis situation. Appreciators of fine arts are, after all, a minority. And although the youngsters at Mumeijuku tell me they don’t mind being nonconformist in that sense… Mmm… Well, let’s just say that the times have changed.

Such a treat. Thank you!

Hey Anonymous. I’m glad you’re digging it. Cheers!

(The next chapter is, I think, the longest one in the book. Working on it now. I hope to have it up in late June.)